The spaces we interact with on a day-to-day basis can often slip by unnoticed, resulting in familiar locations falling into the cognitive background of our minds, and allowing our autopilot to take over. In collaborative spaces, however, these dynamics shift and begin to develop into more complex systems. The problem with these systems and the people interacting with them is within the nature of people themselves – although we may be predictable as a group – we are individuals who demand certain specific needs to be met. Often times these interests are in conflict, after all, you don’t see many Wall Street stockbrokers sitting in children’s daycare furniture. Universal design for everyone serves no one. So, when confronted with the problem to create a space that meshes middle-school-aged children and grown community members of Columbus, what can be done to accommodate both?

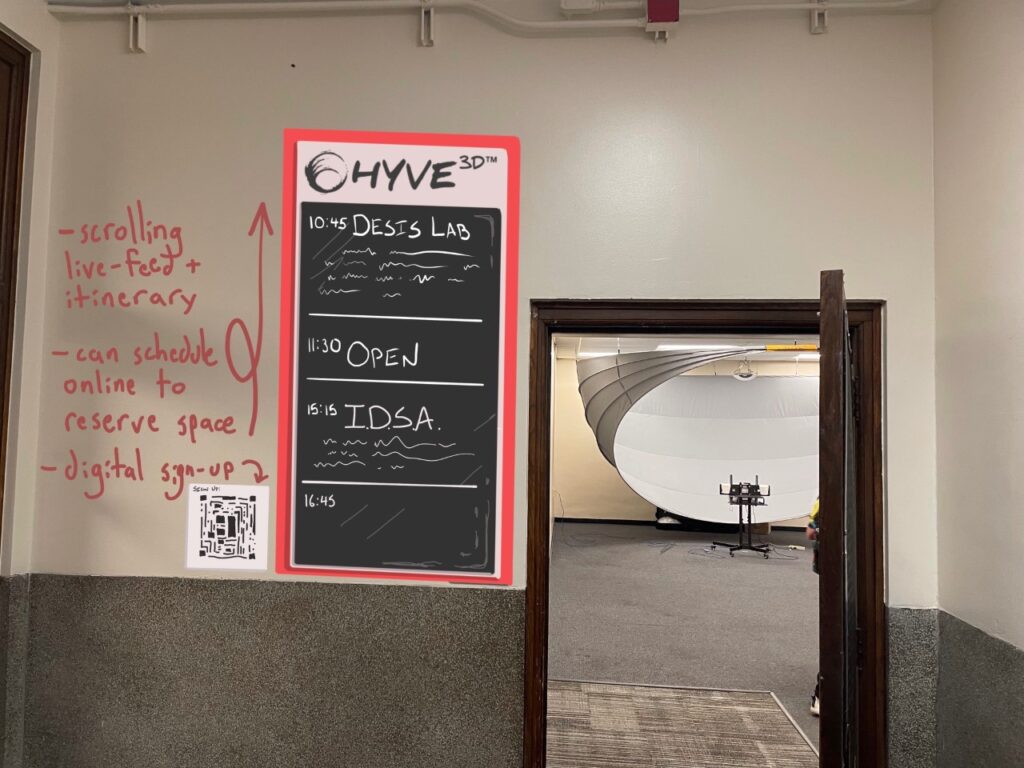

Senior design students at The Ohio State University, including myself, teamed up to collect research in tandem in an effort to further understand this problem. Working hand-in-hand with DESIS Lab, Erika Strazinsky, Mychajlo Johnson, and Sophie Stefanski have and will be designing a system surrounding the use of a new technology in the nearby Dominion Middle School, also available to the larger communities of Columbus. The HYVE-3D is the centerpiece of the system as a whole.

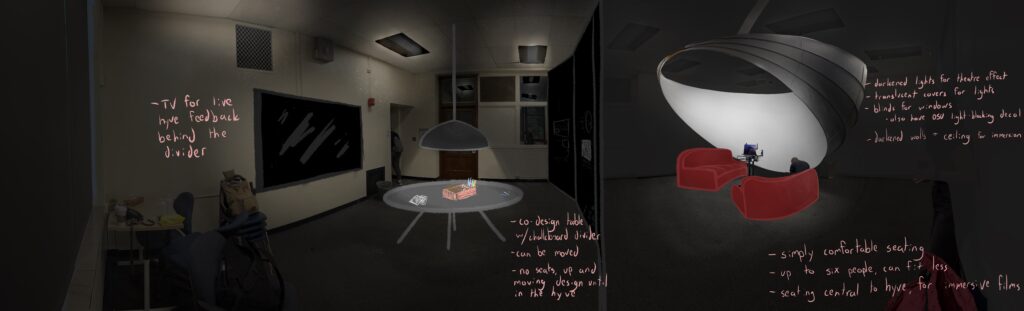

The HYVE-3D is a real-time immersive three dimensional sketching and visualization system independent from the hassle of cumbersome headsets and tangled wires. Using only a 5m x 5m x 2.5m controlled natural light room, a wired internet connection, and a power plug, the HYVE-3D is an elegantly minimal approach to the future of collaborative design. The system’s lack of reliance on head-mounted display and other virtual reality accessories is paramount to it’s accessibility and ease of use, allowing for multiple users at a time, reduced motion sickness, and seamless interaction between the users and the digital workspace. The easy-to-use software can be swiftly learned by any layman, and the 3D sketching utilities can foster worldwide collaboration and teamwork between designers, architects, and engineers alike.

There are several HYVE-3D systems currently scattered across the globe, but there is only one located in the United States – the one we have access to. Sebastien Proulx, the main stakeholder assigning us to the problematic, has expressed the need for the creation of a space to better house the HYVE-3D, currently sitting in a vacant room on the ground floor of the middle school. It is imperative to consider the potential interested parties in the larger Columbus area – involvement from the community is to be expected and prepared for. Due to this, the nature of the space housing the HYVE-3D must accommodate both the teachers/students within Dominion Middle School and any and all other groups of different demographics. This poses the challenge of designing an inclusive system that will facilitate use from a variety of crowds, old and young, educated or not. There is an emphasis on the social availability of the technology and it’s potential use as a helpful and pragmatic system for the people of Columbus.

The team combined forces to create a series of surveys to target different stakeholders. Initially, each member of the team created a 10-question survey (one for the general public, one for communities around Columbus, and another for the adult staff of Dominion Middle School, the latter of which was unable to be sent out) that ultimately gathered a total of 156 detailed responses.

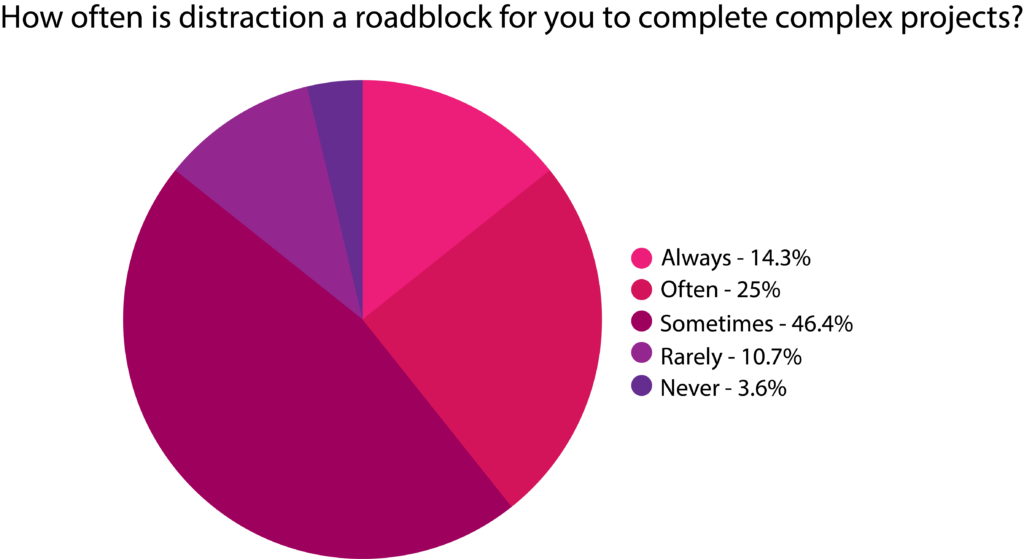

Firstly, the group gauged the participants relationship to their places of work/collaboration, and how distraction impacts their day-to-day. An overwhelming 85.7% of participants from one survey expressed becoming distracted sometimes, often, or always from complex projects. Only 3.6% expressed never becoming distracted when working on similarly complex projects.

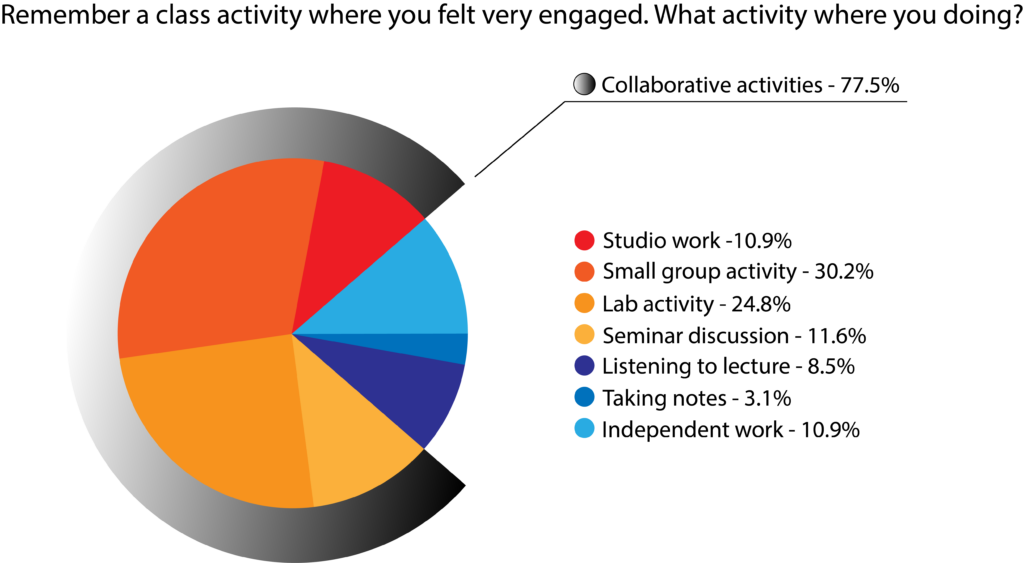

We then wanted to gain an understanding of what exactly makes a room a place where one can get work done. The group asked a series of questions about focus, comfort and more. 77.5% of participant responses stated that, in times of engagement, collaborative activities were the type of pastime that kept them most involved. This may be indicative of people’s willingness to work with others as a tool for effective work practices.

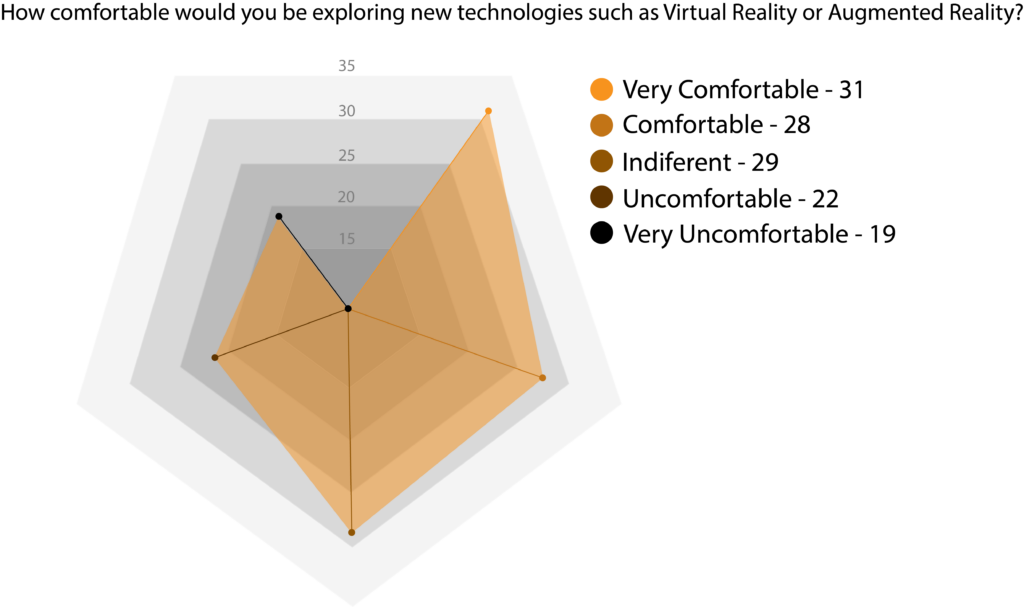

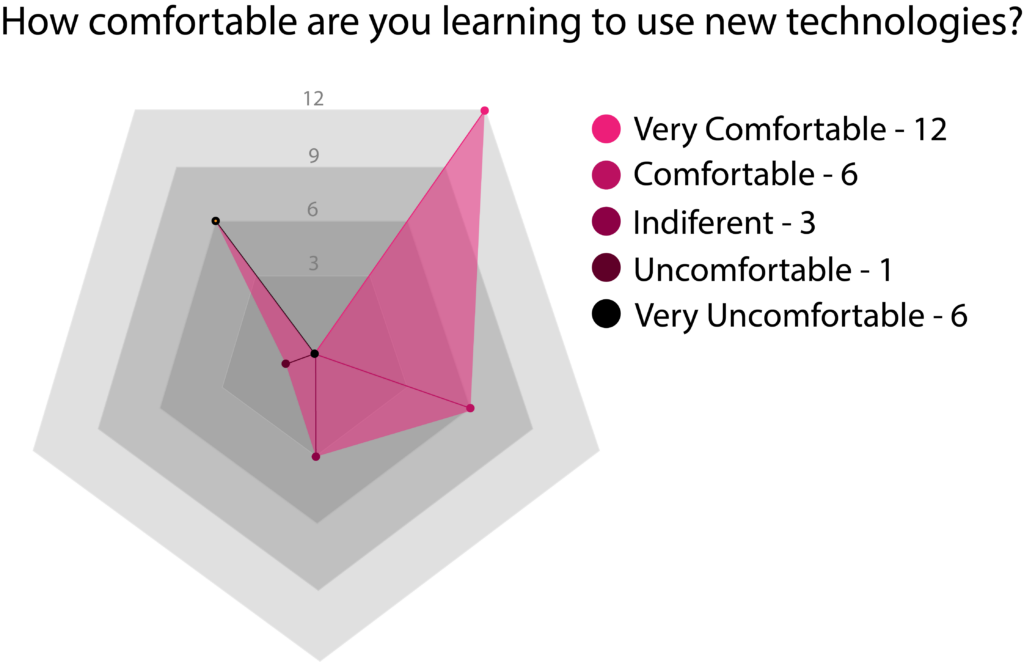

The final part of the survey tasked participants with answering questions related to technology and their familiarity with it, as well as their willingness to learn more. Below are the a few comparisons. Take particular notice where the most volume of the graphs lie. It is apparent that while a majority of people have no problem learning new technological systems, there is also as significant portion of the sample size that not only has indifference towards technological systems, but active discomfort toward the idea. These people are not to be ignores, and it will be worth further investigation to consider this subset of people.

More data visualization can be found on the numbers page of my Newspaper.

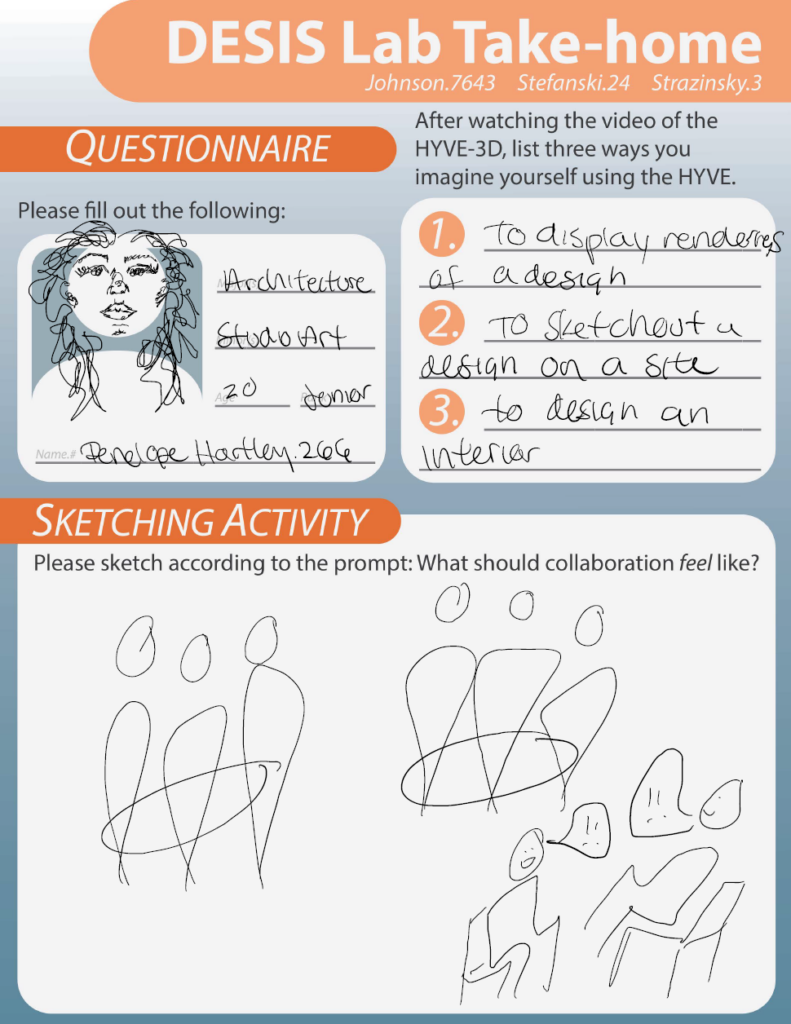

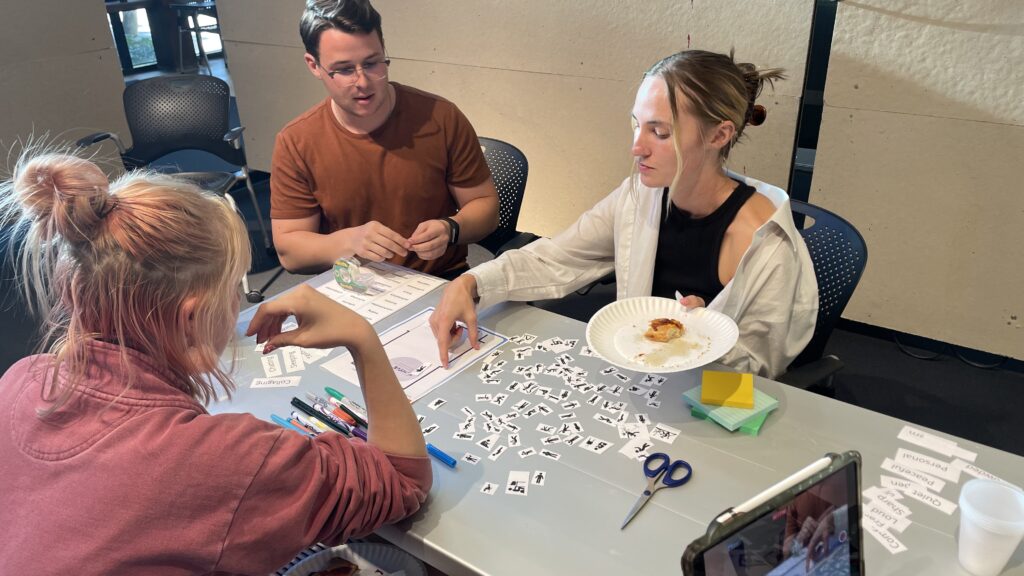

After gathering enough data from the questionnaires, the team continued researching – this time using a series of co-design techniques on a group of seven participants. The volunteers were all Ohio State University students from the Knowlton School of Architecture and the Hayes School of Interior Design and Visual Communication departments.

Before assembly, we gave participants a small take-home worksheet to complete before the day of the co-design event. This was to prepare their way of thinking to be more in-tune with spatial awareness and collaboration. The homework also gave the research team a look into the minds of our participants and helped us decipher some of their later work in the co-design activities.

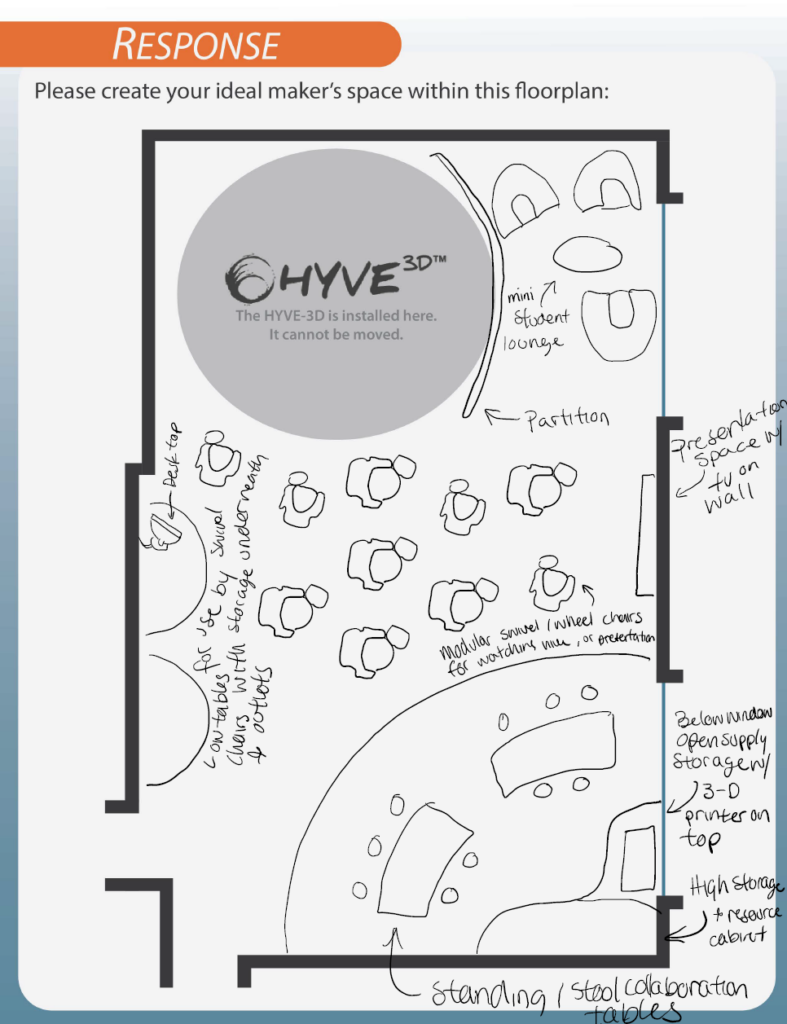

On the day of the event, the team informed the volunteers of their tasks; 1. discuss the HYVE-3D and the take-home work, 2. as two small teams, independently collectively vision a series of spaces utilizing provided abstract materials, 3. react to a series of “provotypes” (provocative mock-ups of different layouts of rooms) and document their responses, and 4. debrief.

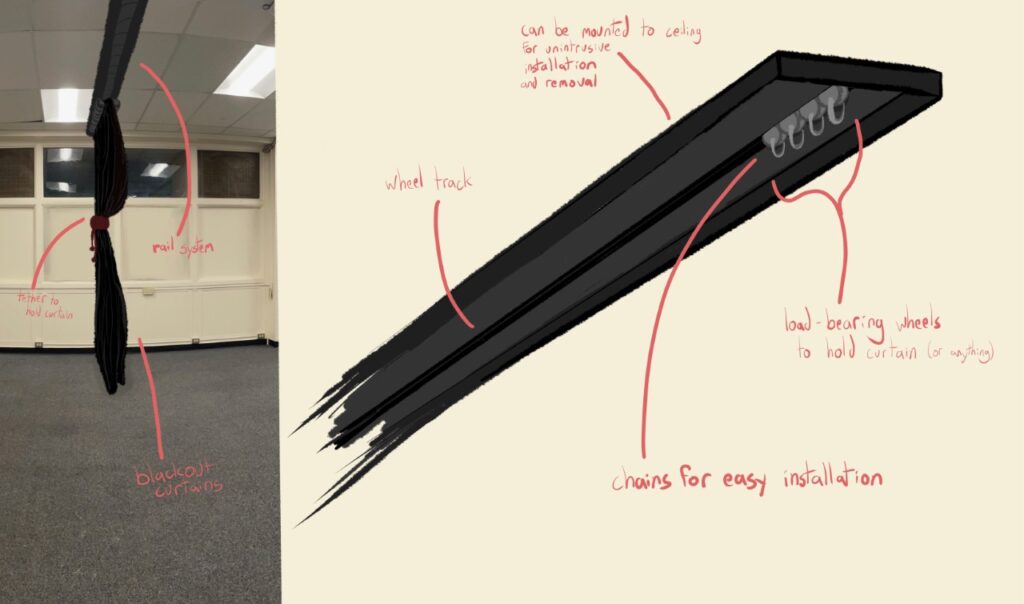

The Research Team learned a lot from the event, mostly in relation to how various furniture layouts impact space and what can create an environment best suited to host collaboration. Participants provided valuable insights into the theory behind the usage of the space, how circulation, flow, and general atmosphere either helped or hindered the HYVE-3D and it’s collaborative goals. It seemed that the most prominent challenges lay within the integration of multi-functional spaces, how they would transition from one space to another, and general limits within the space (no major remodeling, construction, destruction, etc.). The volunteers expressed the need for movement, openness, and fluidity surrounding the system of the HYVE-3D, complimenting furniture and enough technology to keep users engaged but not overwhelmed. They also shared reasonable conservative views of the foreign machinery, stating that the ability to learn and use the system is currently nebulous and distant – something they described as a major deterrent.

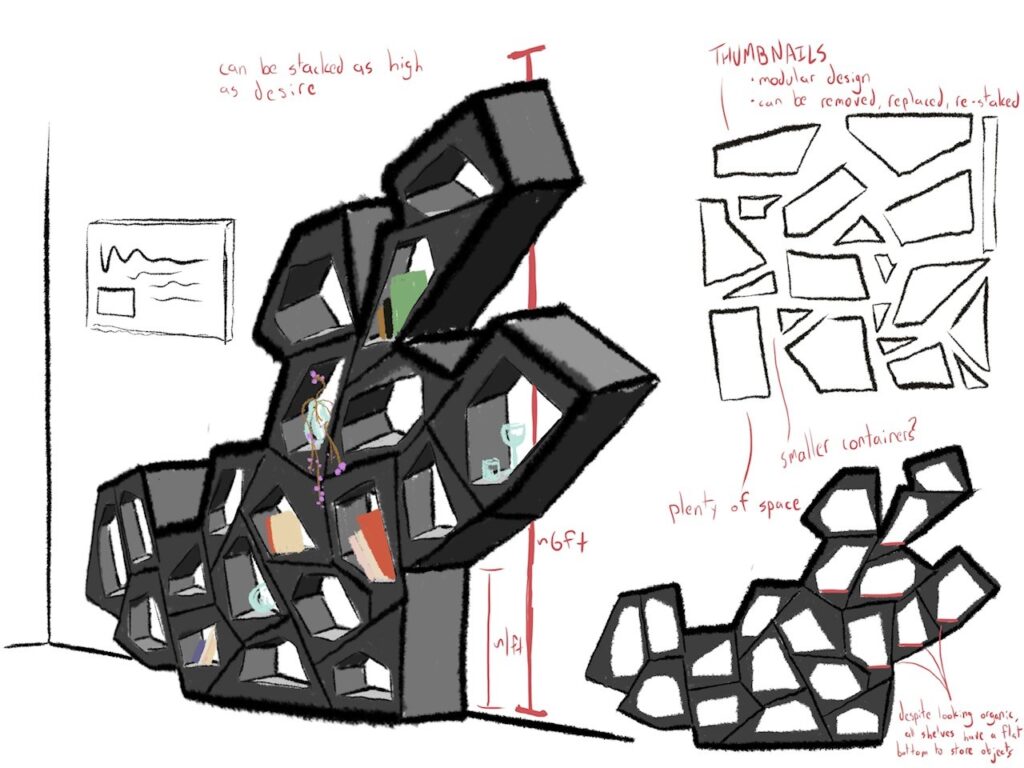

Beyond the communal research gathering, I also personally spent much time reading and analyzing many articles falling under general themes of focus, arts, business, and science and technology. The wide variety of secondary research is documented on my Newspaper page. From these analyses, however, I created a few design conjectures exploring a variety of solutions from the uninspired to the radical. The point of these conjectures was to get the bad ideas out of the way while simultaneously trying out ideas one wouldn’t otherwise try – and perhaps something good will come out of it along the way.

Exploring the system from the four separate points of view allowed for a shift in perspective that effectively created a series of solutions entirely independent and unique from each other. The important takeaways from these conjectures was the early iteration of solutions to the problematic as well as helpful feedback from peers and stakeholders. No one conjecture holds a permanent solution, rather all conjectures have small aspects of success that can (and will) be built upon.

Moving forward, there are many avenues that this thesis may venture down. I aim to dive deeper into the ideas behind some of my conjectures and combine ideas into more fleshed out prototypes that can be tested in the space. Working in the woodshop and experimenting with dimension, materials, and spatial relationship will surely bring about further insights that can inform future decisions in the design process. Brainstorming, C-K mapping, perspective shift, and rapid prototyping will determine the next major strides of my thesis. There is a lot of untapped potential hidden within the division of space and the modularity of the furniture within it. Designing a series of installations and/or furniture systems and/or meshing all of thats with a technological flair intrigues me, and I will continue to tailor my design solution to accommodate all stakeholders, including myself.