To better understand the role artificial intelligence might play in eldercare, a handful of researchers from the Robotics and Innovation Lab at Trinity College in Dublin—and their robot Stevie—moved into Knollwood, a non-profit retirement home for military officers and their spouses, for months-long stretches this spring and summer. Their goal was to understand what aging people and the staff that care for them might want from a robot, and how AI could bridge the widening gap between the number of older Americans in need of care and the number of professionals available to care for them.

Stevie is what’s known as a socially assistive robot. It’s designed to help users by engaging with them socially as well as physically. The 4-foot, 7-inch robot is equipped with autonomous navigation. It can roll through Knollwood’s hallways unassisted, though for insurance reasons—and to avoid even the remote risk of a collision in a community where falls can be life threatening—Stevie never leaves his room without a handler. The voice command “Hey Stevie” activates the robot. Stevie responds to other words with speech, gestures, and head movements.

A robot like Stevie can be useful in care homes in a number of ways. Some are fairly simple and practical: for example, its face can double as a video-conferencing screen, enabling a resident to video chat with a doctor or family member, or a staff member with a resident in another part of the building. It’s possible that a later version of Stevie could go door-to-door taking meal orders on the touchscreen attachment that can be mounted to its body.

The prototype made for Knollwood was deliberately designed as a sort of bot-of-all-trades. The idea was for researchers to observe how residents interacted with the current iteration of Stevie, then go back to the lab and perfect the functions people seemed to want from it most. The assumption from staff and researchers alike was that people would want the robot to do manual chores: to make deliveries, or act as a roving call button. But, generally speaking, residents didn’t want to give Stevie a verbal order and be left alone, they wanted the robot to stay and keep them company. “When we went into conversations with people, especially after they met the robot, [and] asked them what are the things you liked most about it, they’d say, ‘it made me laugh,’ or, ‘it made me smile,’” McGinn says.

One thing we are learning as robots join us on this planet is that, just as there are situations when it’s easier for people to bond with an animal than another person (hence the value of pet therapy) there are also situations in which some people feel more comfortable bonding with an artificially intelligent companion than a human one. The ability of social robots to engender a kind of intimacy may be their greatest asset. The artificial element of that intimacy, however, is also the thing that most worries critics of caregiving robots. “People are capable of the higher standard of care that comes with empathy,” writes psychologist and MIT professor Sherry Turkle. A robot, in contrast, “is innocent of such capacity.” In contrast, ethicists who see potential for positive human-robot encounters argue that robotic assistance doesn’t have to come at the cost of human interaction.

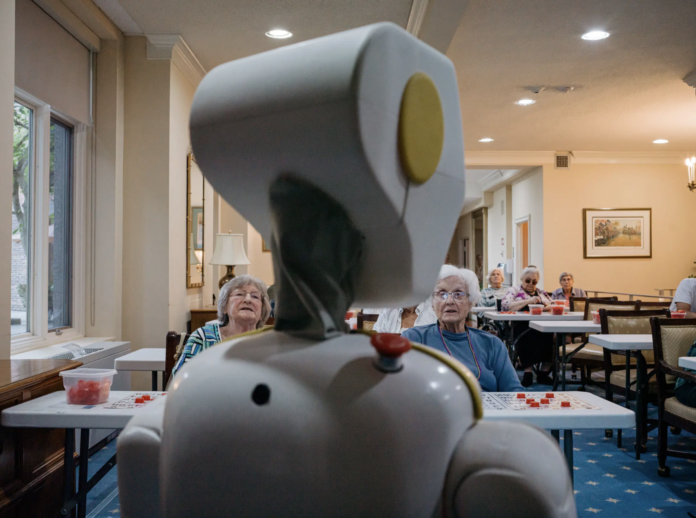

No matter how much comfort a robot provides, it won’t be widely adopted by the elder-care industry unless it provides value to the people purchasing it. Unlike a human employee, a robot can be on its feet—well, its wheels—all day and all night, moving placidly from one room to the next, with the same level of energy and attention whether it’s on its first hour of work or its twelfth. These characteristics make Stevie seem, to some current human caregivers, an unwelcome threat. Menbere Gebral is an activities assistant in the long-term care unit, and she adores her residents. When Stevie and his handlers showed up at a recent bingo session she was a little wary. After one session, though, Gebral was a convert. Stevie called out the bingo numbers, freeing Gebral from the laptop program and leaving her able to interact with residents. She was busy with the parts of her job she likes best, and that most affect her residents’ well being.

Analysis

This article focused on an experimental social robot, Stevie, which was implemented in a retirement home located near Washington, D.C. The goal for the researchers was stated as understanding “what aging people and the staff that care for them might want from a robot” as well as “how AI could bridge the widening gap between the number of older Americans in need of care and the number of professionals that care for them”. I thought it was interesting that the researchers assumed that residents would want Stevie to serve as a butler, but were surprised to find that residents wanted Stevie to interact with them and keep them company. Obviously humans want social connection, whether it be with another person, a pet, or a robot companion. This article is a good reminder to consider the context of the solutions, especially if it involves something as contentious and experimental as artificial intelligence.