What is land acknowledgement? That was the first question I asked myself when I was trying to investigate my topic of interest for this project with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR). I realized how far more nuanced the topic is and there are different viewpoints on land acknowledgements from tribes all over. My goal is to challenge the idea of land acknowledgments that are merely symbolic and lack meaningful action. Instead, I believe that land acknowledgments should focus on concrete, feasible steps to involve and support Indigenous communities. This, in turn, should redefine what a true land acknowledgment represents.”The statements often apologize for “dispossession” or for being present on “stolen land” or “occupied territories.” […] Rather, it anachronistically conflates a people’s presence in an area with ownership of specific property, and it equates grazing or hunting grounds with notions of political sovereignty. (Eugene, 2022) The history, utilization of, and relationship with the land is a way that we can reframe land acknowledgements to recognize, understand, and appreciate the land we reside on. My approach to ODNR’s prompt, “less litter and reduce waste” is how Indigenous Knowledge can help educate and inform present day use of the land. In turn, it also affects the stakeholders: ODNR Staff, Indigenous People, and park visitors. The salient issues I am addressing are the gaps in the historical understanding and its influence on land stewardship, and missed opportunities to leverage indigenous knowledge for park upkeep.

When I asked the park managers about their knowledge about different time periods, 3/4 park managers self-reported they know more about post-colonial history whereas 1/3 park managers self-reported they know less pre-colonial history. Why is the data significant? Frankly, it tells me that state park managers don’t know about the complete history of the land where the genocide and ethnic cleansing of Indigenous people occurred in Ohio. In addition to this, it tells me park managers know more about the history of land the park is in post-colonialism because of how this history goes untold or is sugar coated. This discovery was significant because my area of focus does rely on people being aware of the history of the land in which they occupy and how that influences a positive impact on the way people care for the land.

The prompt given by ODNR for the project is “less litter and reduce waste”. Keeping this in mind, one of my survey questions was asking park managers, “How would you rate overall the impact of each group of people on the cleanliness and upkeep of the park?” The groups I had were families, married couples, senior citizens, and young adults. The rating was from a very negative impact to a very positive impact. In response to this, 17% of these park managers self-reported that these groups have an above satisfactory rating when it comes to the upkeep of the park. The conclusion I drew from that and found interesting is that the stakeholders I chose that visit the park, have a more negative impact on maintenance of the park. So how can that improve? I propose some ideas of how improvement is possible through the interrelationships of the stakeholders at the park.

The three stakeholders are all intertwined in my problematic and can affect the experience and relationship they have with the state parks. It starts with the staff at the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. By becoming more educated on the history of the land there will be more of an understanding and appreciation of the land they reside on. And in turn they will also have supplemental information to knowledge they already have when it comes to preserving and conserving the state parks.

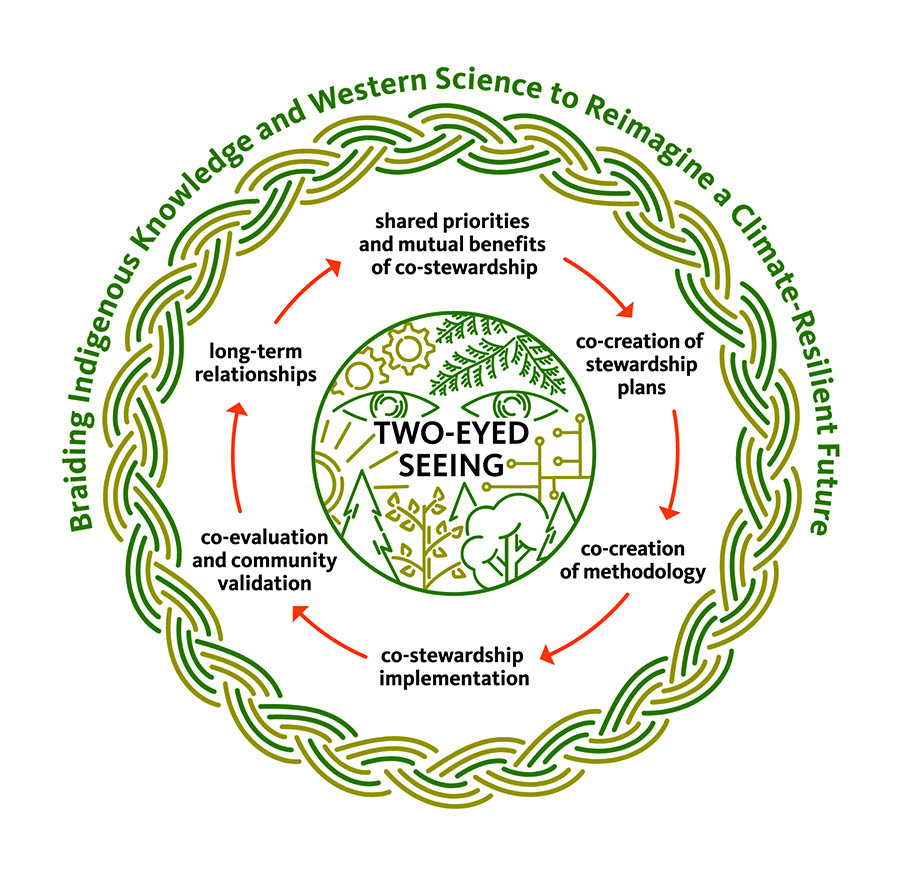

ODNR staff have started to establish a relationship and acknowledge the presence of Indigenous people in the Ohio area by the Great Council State Park in Xenia, Ohio shown below. Land acknowledgements aren’t what the Indigenous people seek always, tribes are all different in the mission they are set on. It is first about establishing a relationship with them and having a genuine interest about what you plan on achieving by taking these steps in the first place. I would love to see ODNR as a whole and/or Ohio State Parks and Watercraft can cultivate more of these relationships with the Indigenous communities. And not a relationship where ODNR does something that is performative but instead works with Indigenous people to create an authentic relationship that will get the original stewards back on their land educating all stakeholders involved on their Indigenous Knowledge.

Park visitors are also a primary stakeholder in this problematic. I already have mentioned how park managers view some of the group’s impact when it comes to the cleanliness of the park. Considering how they are a key stakeholder in this relationship between Indigenous people and ODNR staff, having them also be a part of this co-designing effort to improve the state parks is vital. When I asked, Philip Hutchison, historical programs administrator at ODNR, about whether he believed the locals in Appalachia have acquired knowledge from Indigenous people to apply in their own practices. He does believe this is the case that there has been this acclimation of some practices that the Appalachians have implemented into their lives inherently. Phil said “ A common misconception he said there is about people in rural areas is they aren’t educated and resistant to scientific sustainability methods, in actuality it’s the opposite.” They are connected with nature and they do have this knowledge of nature and although it isn’t the modern scientific method, it should still be held in high regard.

Some common misconceptions about Indigenous people and their practices and way of life I learned about are of high relevance in my focus. One interview I conducted was with Dr. Michelle Wibbelsman, Associate Professor Latin American Indigenous Cultures at OSU. She told me how Indigenous people have a relationship with the land that extends beyond just being a resource it’s not about how you farm the land or extracting from the land it’s about how you also offer something to it, its a reciprocal relationship.This has the potential to redefines the relationship with the land opposed to how western perspective has shaped it. “Our aim is to put in the spotlight practices of re-use among indigenous groups in North Russia to show how much they continue to be discredited as inferior and spurred out-of-need and not as creative and noble endeavors.” (Siragusa & Arzyutov, 2020)

Park visitors are also a primary stakeholder in this problematic. I already have mentioned how park managers view some of the group’s impact when it comes to the cleanliness of the park. Considering how they are a key stakeholder in this relationship between Indigenous people and ODNR staff having them also be apart of this co-designing effort to improve the state parks is vital.

One of the design conjectures I proposed was the drive-in movie. The idea is for there to be an intervention between all of the stakeholders I have mentioned above where a film is shown by the motion picture company, Red Nation Films. They are an independent indigenous film studio that makes it their mission to accurately depict Native Americans stories, and amplify their voices. There are 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S., Abrahamson said, each with a distinct culture, language, ceremonies, art and traditions. She said filmmakers need to recognize that not all Native American people are the same and not “continue to use our people and mush us together like a bunch of potatoes being mashed.” (Kincanon, 2024)

This conjecture has the opportunity to create a space for communion where Indigenous people feel like they can tell their stories to people who show up not just for the film showing, but also to hear the panel discussion. The panel offers a deeper level of critical thinking and opens the floor to ask questions to the speakers (members from the cast, local Indigenous people). This is for ODNR staff, park visitors, or any stakeholder who don’t consider or just don’t know anything about what land means to these original stewards and how far more nuanced these conversations are.

Another conjecture I had was Visual Signage of Indigenous Knowledge that indicates information within these different areas of the park such as, hunting, fishing, agriculture, waterways and forestry. It was inspired by one of my lit reviews that discusses how land acknowledgment relates to the trails we run on. “As an Indigenous environmental scientist and trail runner, I believe land acknowledgments are an important first step in rectifying past harms, but also in increasing awareness of vital Indigenous land management practices that make the many trails we love better for all.” (Jennings & Jennings, 2022) This conjecture feels more feasible if it was pursued however some pitfalls I thought of that don’t work out with the design is how signage gets glossed over, people wouldn’t want to implement these things into their own lives, and there needs to be the consideration of how Indigenous people will be compensated for their knowledge and participation, and that’s to just name a few moving forward.

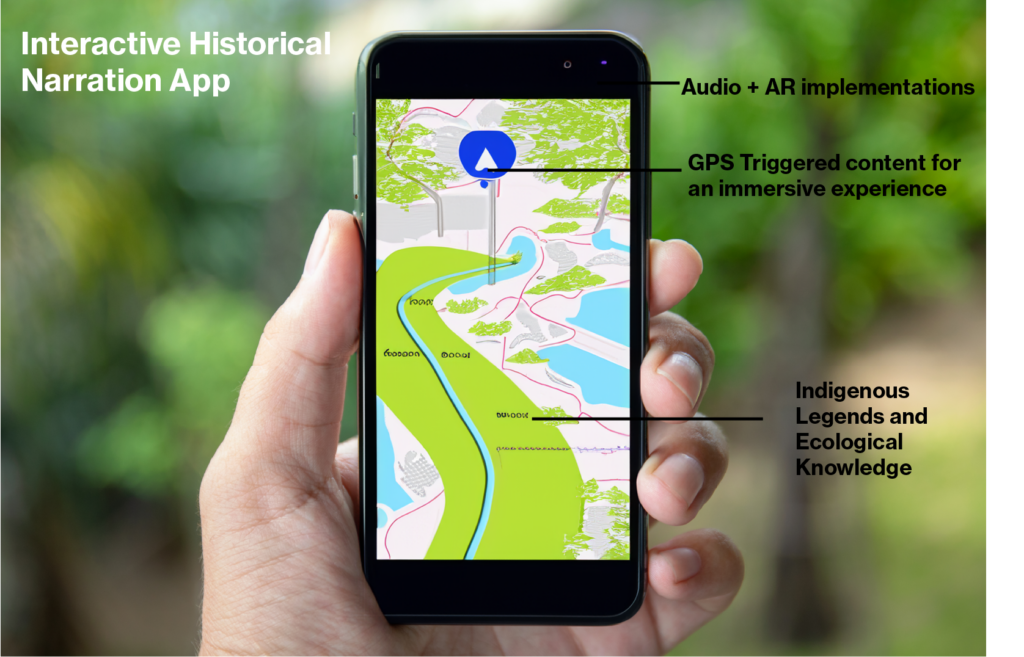

Another conjecture I wanted to include was the interactive historical narration app. As visitors walk through different areas of the park, their app provides stories related to that specific location. These stories will be split into sub-categories on the app interface. There would be an Indigenous Legends, which would be landmarks and areas of significance whether relating to spiritual significance or a location Indigenous people used for agriculture for instance.

Indigenous people were the first original stewards of this land, and their practices that have been passed down generations have been implemented in ways through the Western society. Through the information I learned in this research phase of the capstone I want to show how Indigenous Knowledge from the past can impact the present and future stewardship of Ohio’s state parks.

Sources:

Jennings, L., & Jennings, L. (2022, January 25). Land Acknowledgements And How We Relate To The Trails We Run. Trail Runner Magazine. https://www.trailrunnermag.com/people/culture-people/land-acknowledgements-and-how-we-relate-to-the-trails-we-run/

Siragusa, L., & Arzyutov, D. (2020). Nothing goes to waste: sustainable practices of re-use among Indigenous groups in the Russian North. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 43, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.02.001

Sources:Kincanon, M. (2024, March 12). ‘It is our time now’: Native Creators Discuss Filmmaking Ethics and Positive Changes Being Seen in the Industry. FāVS News. https://favs.news/it-is-our-time-now-native-creators-discuss-filmmaking-ethics-and-positive-changes-being-seen-in-the-industry/

What is TEK? | Traditional Ecological Knowledge Lab. (n.d.). https://tek.forestry.oregonstate.edu/what-tek

Eugene, E. K. (2022, June 10). ‘Native Land Acknowledgments’ Are the Latest Woke Ritual. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 24, 2024, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/land-acknowledgments-are-the-latest-woke-ritual-college-bureaucrats-native-ancestors-11654876804