The inaccessibility of knowledge in scientific discovery comes from many factors including socioeconomic situations, geographic location, and concepts of privilege and colonization in academia.

In the context of paleontology in South America, these factors all combine to create a situation where a large amount of knowledge is stifled from being researched and discovered.

“Despite the scientific wealth of its collections, MPPCN (Plácido Cidade Nuvens Museum of Paleontology), like rural paleontology museums across South America, lacks the funding, staff and technology required to safely store and study its scientifically valuable fossil collection. The facility’s remoteness also makes it challenging for international paleontologists and even researchers based elsewhere in Brazil to access. While vast collections sit in basements like this one, inaccessible to the larger paleontology community, those big questions about prehistoric ecosystems go unanswered” (Elliott, 2024).

“What’s more, the Araripe Basin’s abundant fossils have long made the region a target for smugglers, who fill demand for fossils from both paleontologists and collectors in wealthier nations. Present day fossil trafficking is an outgrowth of paleontology’s long colonial history in countries like Brazil. “The First World has really had a predatory relationship with these areas,” says Silva. “Scientists from around the world would go to these areas and start their own excavations without proper authorization and then smuggle things out” (Elliott, 2024).

So how can we tackle these obstacles while also allowing the indigenous people of Brazil to take ownership of the research and discovery of these paleontological findings?

“Digitizing the museum’s specimens, as has already been done with many collections in the global north, would open a wealth of Araripe Basin fossil data to scientists worldwide” but this effort is incredibly time and resource-consuming. Claudio Silva, the scientist who wants to digitize the fossils within the MPPCN, found that this task of digitizing fossils is not the right way to go in the grand scheme of making knowledge equitable (Elliott, 2024).

“In two short years he resolved to be back, with a device of his own creation that could revolutionize paleontology in South America while making the field more equitable. The innovative scanner he built has the potential to open up fossil digitization to resource-poor but fossil-rich museums across the global south. Since the 1990s, paleontologists have used CT scanners and other commercial technologies to digitize, model and upload fossils to massive online databases like Morphosource. But the global south has largely been left behind, because existing scanners are incredibly expensive, are difficult to move to and operate in remote areas, and require expertise to run and maintain. And transporting fragile fossils great distances to urban centers with scanning capabilities is expensive and risky” (Elliott, 2024).

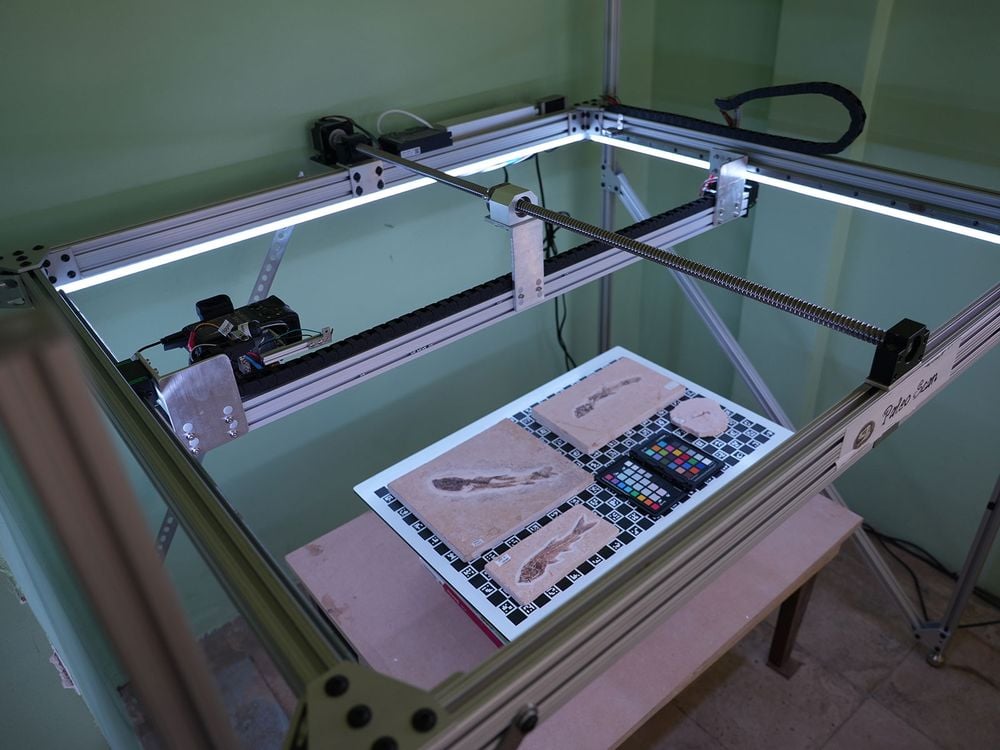

“Back in New York, Silva and his team went into problem-solving mode—they needed to create a new scanner that could quickly and cheaply digitize thousands of fossils at high resolution. Plus, it had to be portable enough to move between rural museums over rough roads and simple enough for museum staff to operate without much training or on-hand technicians. And the scanner had to be able to operate without onsite computers for image processing, which aren’t always available at rural museums. They called the device they came up with PaleoScan. It consists of a high-quality camera mounted to a frame that moves on two axes to take thousands of individual raw photos of a fossil under controlled light conditions. The whole setup is operated by a microcontroller and a touchscreen. After capturing photos, it immediately sends the raw images off to the cloud for processing offsite. The software Silva’s team developed then calibrates and stitches together all the photos into a 3D model of the fossil” (Elliot, 2024).

This realization of understanding the core problem in South American paleontology and the process that came from that reminded me of the design process we use in our classes and how we go about “solving” issues. A real situation was analyzed and design constraints were labeled in order to move forward in creating a solution that could revolutionize science and culture in less developed regions, and therefore their standing in the scientific community itself. It could lead to breaking systematic barriers that have marginalized scientists and scientific discovery around the world.

“Empowering resource-poor museums and institutions to scan their own fossils and provide virtual versions of those fossils to the rest of the world, I think, would really help the scientific community, but also the institutions themselves…He hopes once the collection is uploaded to online databases, the fossil scans will promote more international collaborations with Brazilian researchers” (Elliott, 2024).

Using this case study, how might this process help us understand how to go about improving personal finance and wellbeing individually and in our communities?

References:

Elliott, C. (2024, August 6). This Innovative Device Allows South American Paleontologists to Share Fossils With the World. Smithsonian Magazine. https://smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/this-innovative-fossil-scanner-could-help-paleontologists-in-south-america-180984826/