Rock Climbing is an incredibly popular sport and hobby. What is striking about climbing is how diverse the community is. It attracts a remarkably broad range of people. What each of these people share, though, is that in order to climb, they need a place to do so. If you live in, say, Colorado or West Virginia, you’re in luck. However, for flatter areas with less dramatic geology like Columbus, Ohio, the question of where to climb poses a bit more of a challenge. When faced with a long drive to the nearest real rock to climb outside, many people resort to the convenience of indoor climbing gyms and the world of manicured plastic routes. That said, a new technology exists that could upend this paradigm by providing new ways for people to climb outside.

This Fall, Ohio State’s Center for Design and Manufacturing Excellence (CDME) is acquiring a COBOD BOD2 large-scale concrete 3D printer. This machine represents the cutting edge on the frontier of efficient, more sustainable construction of concrete structures. However, as so often happens in the world of science, the technology has been developed without a clear vision for the range of possibilities that exist for its use. Engineers and architects are captivated by BOD2’s ability to erect houses in a matter of days with little to no human labor, but the reality is this: we have barely scratched the surface of this technology’s potential. It would be a complete shame if such a powerful tool were to be pigeonholed into operating in a single industry or context. This is precisely why, for my design capstone, CDME has asked me to expand this frontier of exploration to see how the world can make use of BOD2’s talents in concrete additive manufacturing.

With a market for outdoor climbing infrastructure and a machine capable of efficiently producing massive rock-like structures, to me, rock climbing and BOD2 are a match made in heaven.

The concept of a manmade outdoor climbing wall is far from a new concept. In fact, over a decade ago, the City of Columbus implemented a large outdoor climbing wall into their design of Scioto Audubon Metropark in the downtown area. It stands today as the biggest no-cost outdoor climbing wall in the Unites States. As one can imagine, this made it an ideal place to conduct my own primary research, not only about the wall itself, but about the people who use it and their experiences. What I learned from them was incredibly insightful.

The first thing I wanted to understand was where people climbed, and why. What draws people to that spot over the other options available to them? In the responses I got to this question, there was an overwhelming consensus. For starters, every person I interviewed cited convenience and proximity as the primary factor for their choice of Scioto Audubon. One young man named Jake said he had just come from the dog park and had some extra time, so he swung by for a session. Similarly, a woman named Michelle who was there with her two sons told me that they come there to get better at climbing with the hope of planning a bigger trip to climb at a real rock venue in the future. A climbing trip is an event that is planned for, but on an everyday basis, people look for a quick option that does not demand any thought in advance.

If convenience is priority #1, though, I wanted to know why these climbers didn’t just go to one of the handful of nearby indoor gyms. Aside from the obvious point that you have to pay for a gym membership, interviewees were quick to point towards a desire to be outside. Jake, the one who had brought his dog said this: “I’ll get a gym membership when it gets colder here in a few months, but I like coming here when it’s nicer because it gets me outside.” Likewise, Michelle and her son said they climb at Vertical Adventures (a local climbing gym) sometimes as well, but they tend to enjoy the outdoor setting. Carson, a local high school student there with his friends, told me that being outside plays a huge role in his desire to get out and climb. Having gotten into climbing this year, he hadn’t yet felt the urge to try an indoor gym.

As part of my primary research, I also conducted a more general online survey about the use and perceptions of public parks. In my results, I found that more than 71 percent of respondents listed “enjoying nature” as a reason for why they go to the park, which was more than almost any other reason people gave. These findings certainly seem to corroborate the testimonials from the climbers I interviewed.

Having established that climbers are drawn to Scioto Audubon for its easy access and outdoor setting, I next wanted to get a sense for the quality of their experience climbing on the artificial wall as opposed to real rock. It was clear that their decision was a pragmatic one: quantity over quality. So, what aspects of quality are sacrificed? This question, more than anything, is the crux of actionable design problems for my project. As expected, the park’s public climbing is far from a perfect solution in the eyes of its users. With the more negative feedback, deterioration and durability were central concerns. The wall was built in 2010, so it has about 12 years of wear and tear, but for a project that large, you would want it to have a pretty long lifespan. Unfortunately, as Zach, age 20, pointed out, the outer composite material has worn down or broken off in countless places on the wall, leaving patches of exposed fiberglass, which would be very uncomfortable or even dangerous to contact. Carson said he actively worries about loose pieces breaking off while he’s climbing, which impacts his mindset. When climbing real rock with too many loose or crumbling pieces, this issue is often enough to make climbers abandon a route and move elsewhere.

I want to take a second to pause and recap what we’ve established so far. Climbers look for the closest places available to them to climb on a day-to-day basis and seek out outdoor options if they’re available. While Columbus is lucky enough to have an artificial wall that meets these criteria, it falls very short of ideal on metrics like quality and durability. Furthermore, the very reality that Scioto Audubon is the largest installation of its kind in the country begs the question of how we can make it easier to produce climbing infrastructure like it.

This is an interesting project to explore the capabilities of COBOD’s printer for two distinct reasons. On one hand, it leverages BOD2’s strengths of efficiently constructing large-scale, durable structures with compelling rock-like textures and imperfections. On the other hand, a good climbing wall demands a level of geometric complexity, nuanced details, and pleasing aesthetic that are not current strengths of construction printing. By addressing the weaknesses of a technology, it opens up new possibilities for its application.

It is no revelation that concrete 3D printing can construct faster and more efficiently than traditional methods at an impressive scale. That’s what it was made to do. Organizations like Habitat for Humanity are starting to successfully test how the machines can drastically improve the rate at which they can construct quality, affordable housing for the people they serve (Taylor, 2022).

The durability aspect is also a promising dimension of concrete additive manufacturing. Concrete is already known for its solidity, but companies like Icon are taking it a step further by 3D printing “disaster proof” homes with a new concrete variant called Lavacrete. The resulting homes are supposedly built to withstand fire, flood, wind, etc. (Englefield, 2021).

One reality of 3D printing and concrete is that there is inherent imperfection in the resulting surface. Extruded concrete is rough, and 3D printing always shows the striations of each layer to some degree. While this could be a drawback in many applications, I was inspired by some cases where this quality was being leveraged instead. For example, in Sydney Harbour, researchers a installing “living sea wall” of concrete panels made in 3D-printed molds to “support easier attachment for barnacles and mussels” (Gillespie, 2022).

My review of literature on concrete printing and adjacent topics also uncovered several main limitations of the technology. With a few exceptions, most projects I’ve seen BOD2 tackle deal with very vertical, simple-surface geometry, such as the walls of a house. This presents a serious problem when you’re trying to mimic rock features. However, according to architect Jack Balderrama Morley in Op-Ed piece, we should not treat 3D construction printing as a stand-alone solution. He writes, “conventional buildings are not made by extrusion or casting or any other single manufacturing process; they are accretions of dozens of different techniques from cast-and-pour concrete to spot-welded steel extrusions to laminated glass. How could one process replace the dozens of others that we currently use?” (Morley, 2022). A part of expanding a technology’s possibilities is exploring what materials and processes can complement it, and a climbing wall is a great venue to do so.

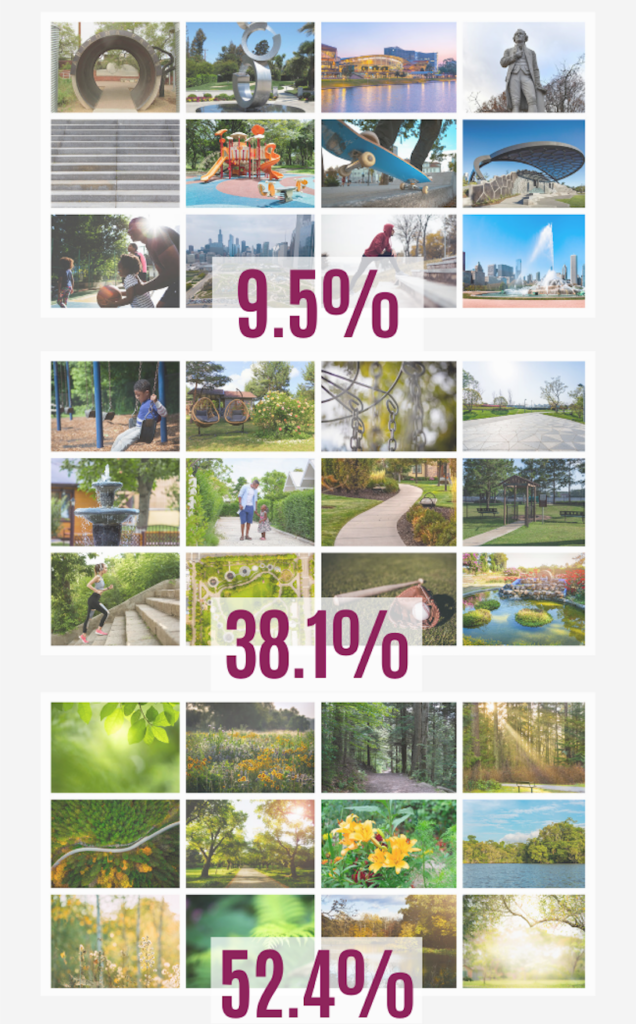

In the online survey I conducted, I also asked participants to share their perceptions of 3D construction printing. In my results, one perception stuck out: 3D printed concrete is not aesthetically pleasing. This is a huge design insight. To be widely accepted and reach its potential, printed concrete is going to have to move beyond its bland, industrial personality. This is especially relevant for use in public parks. In my survey, I asked participants to choose their favorite aesthetic from 3 different photo collages of parks. Only 52.4 percent of people opted for the collage featuring the most nature and greenery. How can we act on this information to effectively introduce a more natural aesthetic to printed concrete.

Rock climbing and 3D construction printing have the potential to be a symbiotic relationship. With flat areas across the country in need of venues to climb, the BOD2 printer has the potential to provide just that. At the same time, COBOD and the additive manufacturing industry can benefit from tasks that push the boundaries of their capability in the interest of overcoming weaknesses and expanding functionality.

References:

Englefield , J. (2021, March 17). Icon builds 3D-printed houses from disaster-proof concrete in TexasJa. Dezeen. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://www.dezeen.com/2021/03/16/icon-3d-printed-houses-austin-texas/

Gillespie, E. (2022, August 21). Living sea walls and kelp forests: The plans to lure Marine Life Back to sydney harbour. The Guardian. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/aug/21/living-sea-walls-and-kelp-forests-the-plans-to-lure-marine-life-back-to-sydney-harbour

Morley, J. B. (2022, June 1). Architects: Here’s the problem with 3D-printed buildings – architizer journal. Journal. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://architizer.com/blog/practice/details/3d-printed-buildings-future-or-gimmick/

Taylor, G. (2022, April 4). See inside habitat for humanity’s first 3D-printed home-and the future of Construction. Bob Vila. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://www.bobvila.com/articles/habitat-for-humanity-3d-printed-home/