Op-Ed Article

By: Meredith Billman

October 1, 2021

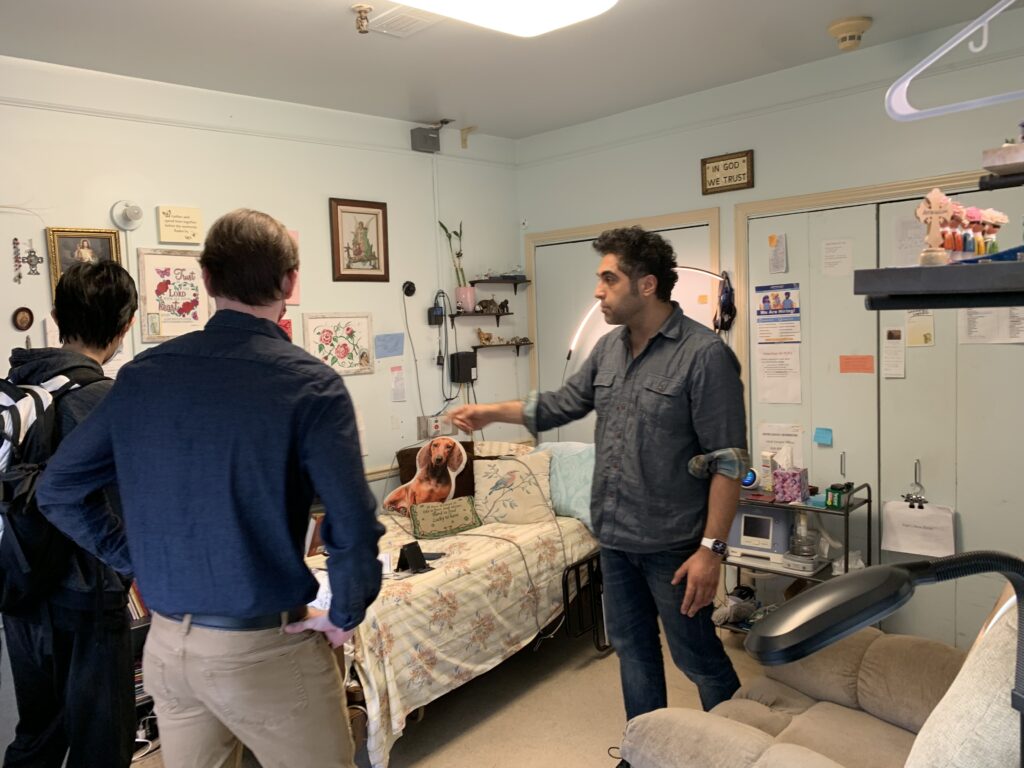

Patti Ruble is a 78-year-old social worker and animal lover living in Columbus, Ohio. Patti became quadriplegic at 12 years old from polio, and her bright spirit has served as an inspiration to many, including Ali Rahimi. The two met while Rahimi was working on an engineering project as a student at The Ohio State University. They formed such a strong bond that after college, Rahimi started Medforall, a startup health-tech company meant to improve the lives of people with disabilities.

Medforall develops remote monitoring technology for people with disabilities. The company utilizes in person support and technology, like cameras and microphones, with the intentions of providing clients excellent health care and peace of mind. Medforall is on the forefront of health care technology and seeks to innovate and destigmatize home care with the help of clients like Patti Ruble.There are many reasons why people are turning to remote monitoring technology. It is becoming increasingly difficult for people with disabilities to receive the health care they need. The global pandemic has exasperated issues like staff shortages, economic burden, and family strain. Additionally, hospitals are reaching capacity with COVID-19 patients, which for many people living with disabilities, intensifies the fear of having an emergency. Remote monitoring technology has the capabilities to bridge those gaps and act as a safety net with more accessibility for less cost.

There are four Ohio State Biomedical Engineering teams working with Medforall on remote monitoring innovation. They are focusing on implementing new sensors like infared scanners and breathing monitors. When the teams visited Patti and another Medforall client, they were interested in anything in the home that might interfere with signals, for example an electric heated blanker. They also wanted to see inside client’s apartments to determine the best place to install the technology.

How does industrial design fit into the puzzle? One article written by Alice Sheppard, a disabled choreographer, dancer, and founder of a traveling dance group, paints an eloquent portrait of the opportunities industrial design has in designing for the disabled community.

“Under the regulations of the Americans With Disabilities Act, the specifications for an ideal wheelchair access ramp are quite clear, as are the defining parameters of maximum gradient, minimum width, appropriate materials, and so on. The codes make no mention of what it might feel like to use these ramps; they focus on what it takes to enter a building safely. Though perfectly usable and necessary, I see these designs as examples of #rampfail. Disabled people want more than access,” writes Sheppard, as she explains the shortcomings of wheelchair accessibility ramps. Working with Alice Sheppard’s disability arts ensemble, students at Olin College took on this challenge and designed a new take on the access ramp. Sheppar describes their new design as, “Unlike the access ramps that enable wheelchair users to avoid stairs, this ramp is beautiful. It is visually inviting; pushing up its surfaces is a pleasure-filled challenge. When we roll down with our hands off our wheels, we and our chairs turn automatically, spinning either out of control into the ground or if we and they are perfectly balanced, turning almost endlessly.”

This is just a glimpse of the power industrial design could hold in enhancing the lives of people with disabilities.

Health care technology and government policies often take approaches similar to the ramp example discussed by Alice Sheppard, meaning they focus on accessibility and meeting health needs. Industrial design can look into the lives and stories of a person with disabilities and design a solution for a human being rather than a human body. Industrialization in this type of health care can be a dangerous technique of the past. The complexity and individuality of each person with disabilities call for a service-type approach that caters uniquely to the individual before expanding. An industrial design innovation in this field is one that embraces the stories and experiences of a person living with disabilities and puts first the humanity of the individual while providing the care they need.

Pictured above is Patti Ruble’s bedroom wall. Her home is covered in evidence of the lives she has touched. There are drawings, paintings, poems, and gifts all over her walls, each with its own story. The black boxes, cameras, and wires on the right control her remote monitoring equipment. The technology looks like an invasion of her home. Patti says that she wished she could have a curtain to cover the mess. She even placed six figurines on one of the boxes. The mess of wires is not only an eyesore but is also a constant reminder of Patti’s health needs. How can this technology be designed into Patti’s space so that it melts into invisibility? How can Patti’s home serve her needs without reminding her of her disability?

Privacy is a huge issue to remote monitoring. The cameras in Patti’s room are connected to scheduled surveillance by Medforall. When first introduced to the technology, Patti was disturbed by not being able to see the person on the other end. Medforall has moved into an approach that is more like Facetime to try to bridge that gap. Still, a woman on Patti’s staff explained that Patti likes to put a towel over the camera because she has anxiety that someone is watching or listening to her outside of her scheduled remote monitoring hours. Another of Medforall’s clients is a young man in his twenties who lives in an assisted living facility due to cerebral palsy, for privacy purposes he will be called Kevin. Kevin declined to have cameras or microphones in his home, and when asked what he sees for the future of health care, he explained that he is afraid of being under surveillance. He even referred to the remote monitoring as feeling like an overlord. Another hesitation of Kevin’s was the misuse of his information. He feared hackers or anyone that could use his data against him. These are concerns that are very prevalent in the disabled community. How can design help to provide feelings of security, safety, and comfort in this industry?

Another big question is what is the role of technology in people’s lives? Where is the line? One major problem with remote monitoring is the isolation of people with disabilities. The disabled community already struggles with social isolation. Patti’s in-person assistance staff consists of about 10 people, who she says are very close friends. Replacing in-person care with complete remote monitoring could take away a support system that is important to the mental health and happiness of clients. An issue discussed with Kevin pertained to automation. Kevin has some difficulty reaching things on his kitchen counter, pouring drinks, and using silverwear to eat. After discussing a potential robot arm that could do those things for him, Kevin explained that he was not fond of the idea because then he would not be doing those things and staying active. Instead, he said he would prefer additional one on one time with an OT and more hand strengthening stretched. Just because technology is possible, does not mean it is the best choice for the client’s life.

The goal of this industrial design project is to design for Patti and Kevin a small improvement to their daily health care. The project must blend into their lives and homes and become an invisible improvement. The solution must also bring peace of mind to the fears that come along with home-monitoring. Lastly, the project must address the ethical limits of technology, prioritizing the human life over the human body. The next steps for this project are to continue to shadow Patti and Kevin, and take a small slice for improvement.

Sources:

https://www.dispatch.com/news/20190225/technology-increasingly-bridges-gaps-in-support-for-disabled-ohioans