The back seat of a car is a space that most Americans are no stranger to. Many people have specific memories and experiences that contribute to their current perceptions of a rear seat car ride, be they pleasant, or unpleasant. However, as automobiles continue to develop according to specific user needs and as they continue to evolve with changing technology, the back seat environment is expected to follow suit.

In a sponsored partnership with Honda, this project seeks to innovate the backseat passenger experience in Honda mid-size SUV’s by implementing a new rear seat convenience feature. Not only will the addition of such a feature give Honda vehicles a competitive edge in the automobile market, but it will also serve as a transitional space for future gen vehicles and their associated interior functions and market scope.

Just what is needed in a back seat experience to make it a good one? Per the norm, this is heavily dependent on the needs of the occupants of the back seat. The target users were defined at the start of the project by Honda as car buyers aged 18-29, and young families in that relative age bracket with children aged 1-10. Members of the primary target audience are likely to be preparing to purchase their first new vehicle and/or are likely interested in participating in future business models expected to hit the automobile market. The secondary target users may be seeking a vehicle as they plan to accommodate their children, who would be the vehicle’s most frequent rear seat occupant.

With the primary and secondary research demographic established, a five-part primary research plan was developed in order to better understand users’ back seat behaviors. The plan consisted of the following:

- A LEGO build activity followed by a short structured interview that served as a way to learn what both parents and children need in a back seat experience and what interactions occur between them

- Ethnographic observations done on short vehicle trips to better understand how various types of passengers exist within a currently existing back seat environment

- A survey designed to collect quantitative data about public perceptions of autonomous vehicles and general attitudes regarding vehicle safety

- A guided journal worksheet that allowed participants to share their idea of a pleasant back seat experience and what they think future ones could look like

- Unstructured interviews with individuals that have mobility limiting disabilities, addressing the accessibility of automobile seating

In addition to the primary research plan, secondary research was conducted in order to better contextualize the social, political, environmental, and economic setting of the problem space, as well as account for future technological and business trends that are expected to take place between now and the next 25 to 50 years.

Research Results

Following the first round of ethnographic style research, performed on both children and adults, research suggests that there are some similarities in needs, as well as some substantial differences that need to be accounted for. Children were observed to not be able to tolerate longer car rides as easily, as they needed frequent breaks and needed to follow a more rigid schedule. While adults have a bit more freedom in this department, they still indicated that a car ride was an experience that was tiresome. Both children and adults expressed a need for media integration for their respective devices, with kids using tech such as tablets, music players, and gaming systems for meeting their personal entertainment needs while adults used their smartphones for both entertainment and productivity. Finally, both user groups expressed that they had better car rides when there was ongoing positive social activity between passengers.

The results of the LEGO build/interview activity were able to shed a significant amount of light on the experiences of kids and their parents while in a vehicle. It became apparent that the associated intensity and types of experiences were going to vary depending on the age of the children in the back seat; for example, a parent with a one-year-old with limited verbal communication capacity is much different than that of a four-year-old, yet similar in many ways.

One overreaching observation that held true throughout all of the participants in this component of the research was that kids have a lot of stuff. Depending on their age, parents were likely to have had to navigate vehicle storage spaces in order to keep their kids happy while on the road. For example, items as large as portable cribs, bags with changes of clothes, heavy car seats, and storage for items such as toys, books, and games were all accounted for in some form by parents during the interview as they discussed regular car trips with kids. They noted that the process of arbitrarily storing their children’s belongings in hard to access spaces in the vehicle was a frustrating experience, particularly as the vehicle was moving.

Another specific element to consider from this section of the research was that there was limited visibility and interaction that was occurring between passengers in the back seat and those in the rest of the vehicle. Parents of younger children in rear-facing seats indicated that visibility of their child was something that they did not feel was addressed well in vehicles, and would appreciate it if they had the ability to be more attentive to their children’s state of being and attuned to their needs while operating the vehicle. It was commonly stated that parents would often ride in the back seat with their child while their partner drove. This served especially useful when children would drop something while in the back seat, as the parent in the back could pick things up for them and avoid having the child become upset. However, when only one parent in the vehicle is present, a dropped item can quickly turn out of hand and create a negative experience for both a parent and a child, as the driving parent cannot turn around to retrieve a dropped item for the child, and a young child will likely express a negative emotion in response to the situation. From a secondary research perspective, we can see this problem getting solutions such as a rear facing front seat designed for children’s car seats (1), to the top 10 family friendly vehicle modification products available for purchase on Amazon (2). From these two articles, it’s clear to see that the way parents and children communicate while in a vehicle environment has plenty of potential for design intervention.

However, despite temper tantrums from dropped items, fights with siblings, and the need to know how to play Tetris with children’s belongings in order to store them neatly, both parents and children expressed that the two elements that made a car ride a good one was effective integration of media and pleasant social activity between everyone in the vehicle. Especially during the LEGO builds conducted, children reported firsthand that they wish to see emphasis placed on their entertainment while in the back seat. In addition to many sentimental moments shared by the family when in a vehicle that were shared by parents in the interview, the children in the LEGO build revisited the idea of putting more social seating arrangements, like a lounge or bar style seating, in a vehicle that would allow for more of those pleasant social interactions that both parties expressed as making a car ride better.

The noticeable phenomenon present in the guided journal activity was that even though participants were excited to possibly partake in activities such as reading, working, and sleeping while a vehicle drove itself, all participants indicated a substantial degree of skepticism for the future as cars begin to turn autonomous, when asked to plot their feelings on an axis. There were substantially higher indications of negative associations, such as “suspicious” or “nervous” as opposed to positive ones.

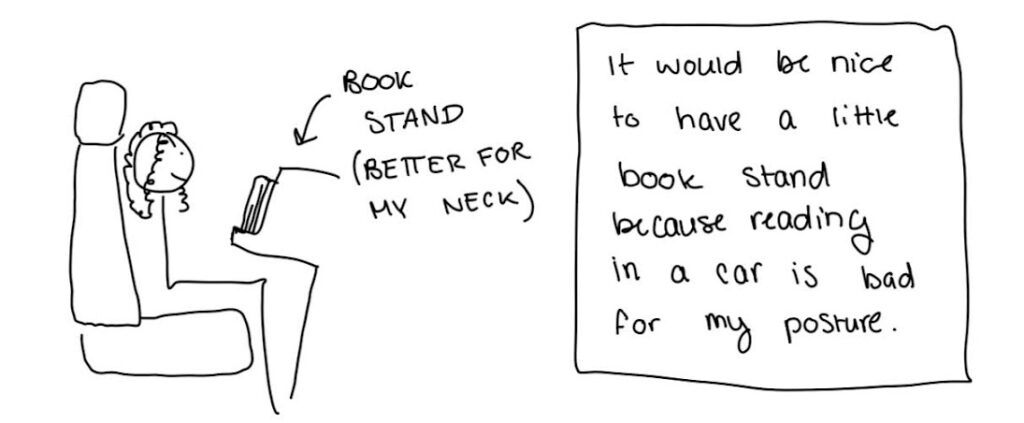

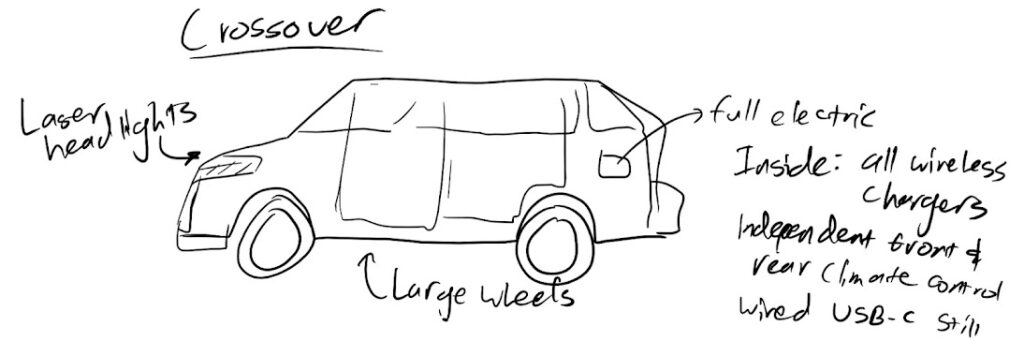

When asked about what features they were interested in seeing, there were several suggestions, usually dependent on the personal interests of each participant. Some common responses when asked what modifications they would like to see in future vehicles were things like leg room, more storage pockets, and more charging ports, just to name a few of the most common responses.

That being said, the participants of the guided journal were similar to that of the parents in the LEGO activity/interview due to the fact that they wished to see improvement in the same three areas, space, storage, and media and tech integration.

Additionally, when asked to describe the best car ride experience that they could remember, guided journal participants demonstrated another similarity to that of the parents and children by sharing several accounts of pleasurable social outings that took place in a car. There were many instances of participants describing experiences in vivid detail that they had spent with friends or family on car trips, and despite describing notably uncomfortable things, such as little leg room and minimal storage, participants still described the ride as being good, simply due to it being social.

With the combined skepticism of new models of vehicles as well as the excitement for new features and activities that would happen in such vehicles, all of the guided journal participants indicated that they would like to have flexibility in their activity – meaning that they aren’t quite ready to trade a more traditional back seat experience for a new one just yet. Responses typically looked like “I’m excited to possibly sleep in the back seat of a vehicle, but I still want to be able to look out the windows and daydreams,” for example. According to a recent Consumer Report (3), “car shoppers want advanced safety features that keep them from getting into a crash, but they’re less enthusiastic about technology that drives for them.” To put it simply, drivers in 2021 are more interested in features that are designed to help them be better drivers, rather than a feature that takes away some of their control. This will be important to keep in mind because from this insight, it will be critical to create a space that is transitional in nature. The results of this part of the journal also continued to affirm the need for a space that does not limit movement, provides for adequate personal space, and is customizable per each passenger.

From the disability interviews, it became clear that participants tend to use parts of the vehicle that often go overlooked, such as handles, or would use pieces of the car in unexpected ways to help feel more comfortable in the back seat. Space and ergonomics is something they really expressed a need for, driving further exploration into secondary research in the science section.

Similarly to the results from the guided journal, the results of the survey suggest that even though users are excited for new features, tech integration, and interiors, they are concerned for their safety being reliant on a computer. We got answers and narratives expressing various points of view that helped supplement the direction of the secondary research, and found that public perceptions of autonomous vehicle technology was dependent on several variables, from gender, to age, to geographic location. It was concluded that though autonomous vehicle technology is expected to grow exponentially over the next 20 years, education and trust in the safety of autonomous vehicles is not progressing at the same speed.

Actionable Insights

From the observations recorded in the five-part primary research plan, five key elements to consider were determined following research analysis.

- Social Interaction – Both target demographics indicated that vehicle experiences were better when positive interactions between passengers happened, such as meaningful conversation or playful banter, for example. It is important for individuals to feel like they truly are enjoying the company that they are in, and passengers could benefit in a multitude of ways if the space they inhabited initiated more of these social interactions.

- Interior Space – Both older and younger individuals desire a more spacious interior that can accommodate their personal space needs as well as their temporary storage needs. Both groups appear to grow weary or restless when the car ride was long, cramped, or when their positioning was not comfortable or customizable to their needs.

- Media and Technology Integration: Children expressed a preference for a system in the back seat that could allow them to integrate their personal devices, music, and gaming consoles into their backseat experience. Adults also indicated a desire for the same type of technology integration in the back seat, but would rather have it work primarily with their smartphones for both productivity and entertainment purposes.

- Storage: Though each of them have different respective storage needs, both target demographics indicated a need for more deliberately designed storage solutions for their belongings. Children tended to have a larger volume of associated possessions when compared with that of adults.

- Flexibility: Both users want to inhabit a space that allows them to do a variety of activities besides simply sitting along for the ride. Though users are excited for vehicle interiors to change, it’s important to give them freedom to choose between more traditional car activities, such as looking out the window, and more autonomous vehicle activities, such as reading, working, eating, sleeping or socializing.

In order to properly contextualize the results of the primary research with the rest of the larger problematic, a discussion of the social, economic, political, and environmental issues at stake must be conducted.

Firstly, most people are skeptical of the switch to autonomous vehicles. Though they are excited for new features, most question if they can rely on AI to safely get them to their destination. Vehicles are expected to rapidly transition to more electric, autonomous models, and personal ownership of a vehicle is expected to be replaced by transit as a service. According to Klaver (4), “AVs have the potential to be a catalyst of seeing mobility not only as a product (owning a vehicle) but as a service or a combination of these two.” This is expected to uproot the economy for automobiles, and to have long lasting effects on not just vehicle production and passengers, but it’s expected to alter the job market and usher in changes to public transport and infrastructure. An article by Vox states that the introduction of AV’s “would destroy thousands of jobs (think of everyone who drives for a living, including truck drivers). But they would also open up mobility to huge classes of people who, due to age, income, or disability, have been unable to get around independently” (5). Since public education on AV’s is not progressing at a comparable rate to the evolving tech, there is a degree of mistrust in AV’s that is prevalent in both primary and secondary research results.

Secondly, a large market currently exists for car accessories and modifications that help better vehicle experience for users of both demographics. Current solutions address common problems such as keeping vehicles organized, optimizing space, and even cosmetic adjustments. It will be key to understand the problem that these problems seek to remedy and to implement the understanding of this into the design of the feature.

Third and finally, personal vehicle ownership is currently more prevalent in areas that allow cars to be a primary mode of transportation, and the rate of vehicle ownership is significantly lower in highly urbanized areas with a reliable public transit system, compared to more rural areas (6). Additionally, access continues to remain a point of interest, as a new spacious Honda may still be an unfeasibly expensive option for middle and lower class families. Vehicles of this nature are less accessible to women, POC, and those in lower socioeconomic brackets (7)(8).

As all of the main points of the research are tied together, potential project objectives begin to float to the surface. The following is an itemized list of objective goals that need to happen as the transition to design begins.

The primary objective is to create a rear seat feature that allows a car interior to be a more social space by initiating positive connections between passengers of both target demographics. In order to accomplish this, the feature will:

- Prioritize passenger comfort, wellness, technology integration, and convenience.

- Initiate positive social activity between passengers in the rear seat and the rest of the individuals in the vehicle.

- Serve as a transitional space from older car models to newer, more autonomous ones.

- Account for space and customization needs of both target audiences.

(1) Coffey, L. (2015, July 8). Volvo turns parents’ heads with new car seat – in the front seat. TODAY.com. Retrieved September 24, 2021, from https://www.today.com/parents/volvos-new-concept-puts-child-car-seat-front-seat-t30981.

(2) Kiely, D., Hall, S., Esler, N., & McNamara, S. (2021, September 7). Cruise control: 18 clever car accessories. Mum’s Grapevine. https://mumsgrapevine.com.au/2015/02/clever-car-accessories-roundup/.

(3) Barry, K. (2018, July 18). Shoppers want car tech that helps them drive better, survey shows. Consumer Reports. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from

https://www.consumerreports.org/car-safety/car-safety-survey-new-car-buyers-want-advanced-safety-not-automation/.

(4) Klaver, F. (2021, January 7). The economic and social impacts of fully autonomous vehicles. Compact. Retrieved September 25, 2021, from https://www.compact.nl/en/articles/the-economic-and-social-impacts-of-fully-autonomous-vehicles/.

(5) Plumer, B., Klein, E., Roberts, D., Matthews, D., Yglesias, M., & Lee, T. B. (2016, September 26). The way we get around is about to change: The new new economy. Vox.com. Retrieved September 26, 2021, from https://www.vox.com/a/new-economy-future/transportation.

(6) Hilgarter, K., & Granig, P. (2020). Public perception of autonomous vehicles: A qualitative study based on interviews after riding an autonomous shuttle.

Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 72, 226–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2020.05.012

(7) Car access: National equity atlas. Car Access | National Equity Atlas. (2018). Retrieved September 30, 2021, from https://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Car_access#/breakdown=7&geo=01000000000000000&geo_type=07.

(8) Claire, M. (2021, February 25). Cars and sexism: Why the industry needs to make cars for women. Marie Claire. Retrieved September 26, 2021, from https://www.marieclaire.co.uk/life/work/cars-650207.