Before March of 2020, the people working in grocery stores, sanitation, healthcare, delivery, and public transportation were considered “service workers.” Most of these jobs were overlooked and deemed undesirable due to their low pay. However, as the coronavirus creeped into the U.S. and was finally taken seriously, it became apparent that these service workers are essential.

When the U.S. was in lockdown from March to May, people were ordered to stay home, whether that means working or attending school from home. Meanwhile, essential workers were still physically going to work to provide essential services like food, transportation, and healthcare to us. They put their lives at risk in order to keep society and the economy running.

Among the essential workers, those working the transportation sector are often times forgotten. Doctors and nurses are applauded for their work in treating patients with COVID-19. Their work is invaluable and we are grateful for their service, however, transportation workers also deserve our appreciation. Many rely on these public transit workers for their daily commute, including other essential workers. Using public transportation during a global pandemic is risky, but some rely on it as their only source of transportation.

In a closed space that holds different people coming in and out, buses and trains can be a breeding ground for COVID-19. Especially if masks, social distancing, and proper sanitation guidelines are not being followed. This poses a serious risk for public transit workers as they drive a vehicle for hours while having to interact with passengers.

Transportation workers face the problem of receiving little support from their agencies in regards to obtaining enough PPE, enforcing rules for passengers, and maintaining a safe work environment with sanitation resources.

“The transit agency I work for very rarely enforces the wearing of masks while on board the trains,” said a rail transit worker I interviewed.

Ideally, interactions with passengers should be limited. But without the enforcement of masks, if a passenger needs to ask a question and they aren’t wearing a mask, this is a danger to the transit operator. Where to enter and exit the vehicle, pay the fare and how to communicate with the operator safely are questions we must answer. As allowing passengers to interact with the transit workers upfront can be perilous.

Another concern according to my interviewee, is the HVAC system in the train. The HVAC system helps regulate the train’s temperature and ventilate the air. However, in order to cool the air in the entire train especially in the operator’s cab, which is separate from the passenger compartment, all the air has to come from the passenger compartment. My interviewee notes that he can smell every person’s body odor, “every time a person expels bodily fluid, every particularly noxious fart of passengers who sit in the section directly behind” him. The HVAC system could spread airborne droplets, which is dangerous. If he can smell everything, then these droplets are likely coming through. Hopefully there are filters in the HVAC system or windows are open to dilute the air. Nonetheless, this is also another area to explore and consider.

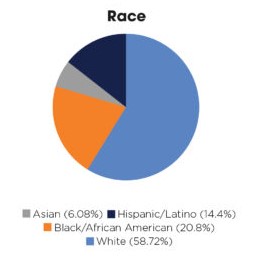

Many transportation workers and essential workers in general are also black, Latino, women, and immigrants. If we address the race gap in COVID-19 deaths, you’ll see that the death rates for the black and Latino population are higher than that of white people and Asian Americans. There is a correlation between the race gap and those working in essential services. Since many essential jobs are low paying jobs, issues like homelessness and overcrowding in apartments in high rent cities, like New York City and Los Angeles, are detrimental to these communities (Walker 2020). This also brings in the fear of bringing COVID-19 back home after hours at work.

With the spread COVID-19, another issue became more prevalent: racism.

As Trump dubbed the coronavirus or COVID-19 as the “Wuhan Virus” or the “China Virus,” more people began to blame Asians for the pandemic. Racism against Asians skyrocketed, resulting in blatant verbal and physical assaults towards Asians regardless of their ethnicity. To some Americans, all Asians are Chinese and the cause of COVID-19. Goes to show how ignorant some Americans are and how racism is a never-ending issue. Let’s not forget what happened this summer to George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many more innocent black lives. But with the Black Lives Matter movement gaining more supporters there is hope and is one of the few beacons of hope during this pandemic of COVID-19 and racism.

As for why I brought up racism during this pandemic… Through my research, I’ve seen quite a few articles addressing racism directed towards an Asian American bus driver. Asians only make up 6.08% of the transportation workers in the U.S., so their voices aren’t as prevalent in this sector (“Employed Persons” 2020). However, the majority of the 6.08% working in transportation likely reside in states with a high Asian population like California and New York. So when the Asian bus driver in San Francisco attempted to enforce the mask rule on a few passengers and was then assaulted both physically and verbally, I understood why. This anti-Asian sentiment as a result of COVID-19, has exacerbated the violence against Asians and consequently Asian essential workers.

“It’s constant verbal abuse from passengers all day long,” said the San Francisco bus driver (Beckett 2020).

The same article also mentioned that just in the month of July, several bus drivers have been assaulted for trying to enforce the use of masks in California, New York, Texas, and France (Beckett 2020). This verbal and physical violence towards transit workers is not solely race based, but often times is. This violence has been a reoccurring problem during COVID-19 and pre-COVID-19.

Even before the pandemic, transit workers have been experiencing a multitude of abuse from passengers and irate drivers.

Transit workers have to deal with intoxicated passengers and passengers who refuse to pay the fare or are frustrated by delays. Most disputes are over fare prices. Those working during the late night and early morning in a dangerous neighborhood may experience potential violence. Gender based violence is also an issue as there are both male, female, and non-binary transit workers. Being almost confined in the driver seat, transit workers have a limited escape plan and space to defend themselves or hide when it comes to in-vehicle attacks (“Transit Advisory” 2015).

Some attempts at protecting bus drivers are protective infrastructure, involving a glass cage and more cameras (“Transit Advisory” 2015).

According to Terrence Layne, a New York City bus driver, every bus driver has stories about passengers screaming/cursing at them and calling them racial slurs. He estimated that he gets called a racial slur “five or ten times a year easily” (Gonnerman 2020). Five or ten times a year may not be that often, but this is still unacceptable. He has even been attacked by an angry driver with a steering wheel lock (Gonnerman 2020).

Obviously, not all transit workers’ and passengers’ relationships are troublesome. There are neutral to positive relationships between the two stakeholders.

When looking at the overall relationship between the primary stakeholders, the transit workers and the passengers, it is often transactional one. Passengers must pay a fare in order to receive a ride. Though during a pandemic, fares may be waived to limit interactions between the transit operator and the passenger or to help the community that is also struggling. Besides this transactional relationship, a protective relationship exists as well.

Not often mentioned, transit workers act as figures of authority since they are trained, are extremely knowledgeable about the streets, and can alert further authorities. When getting on a bus and if you feel like someone is following you. People often advise you to sit near the bus driver or let them know of this potential danger. Bus drivers are seen as protective figures in this case. But how does this protective relationship change during a pandemic? Is the protective relationship even necessary due to social distancing?

Transit workers and passengers also have a social relationship. Pre-pandemic, it was normal to strike up a conversation with any transit worker as they are friendly faces of the community. These conversations must be kept short because there is an unwritten rule, where you should not talk to the driver while they are driving because it can be distracting.

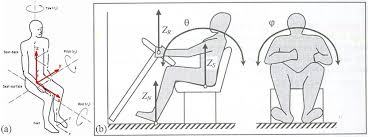

Another interesting pain point Layne brings up is that when driving on uneven grounds and over potholes all day, bus drivers experience this often chronic condition termed “whole body vibration.” He describes this condition as a box of crackers being shaken up forcely, leaving broken crackers. This is what happens to the bus driver’s skeletal system overtime. This causes pain in their back and legs, which often leave the older bus drivers in pain and cause them to limp and walk slowly (Gonnerman 2020).

Layne’s reflection on the “whole body vibration” condition reminds me of hand-arm vibration syndrome (HAVS). Which is common in people like construction workers who often wield vibrating power tools like jack hammers. This condition causes numbness in fingers, loss of muscle, nerve damage, and white fingers (:“Not-So-Good Vibrations” 2020). Due to the similarity of both conditions and with Layne’s account being vibrations sent through the entire body, this condition could leave devastating effects on veteran bus drivers.

I look back to riding the school bus in elementary school. Most of my bus drivers were black women and the ones who have been working for 15+ plus years often walked with limp. As a kid, I always wondered why some of the bus drivers would walk slowly and carefully when all the kids and teachers would run around. Layne answered that question of mine. This would be an interesting problem to look further into.

From not enough PPE, to coming in contact with COVID positive passengers and bringing it home, to verbal and physical assault due to various factors, to health issues derived from working, it is evident that there are many pain points that transit workers experience. It would be worthwhile to further analyze and design for this topic.

Works Cited:

Beckett, Lois. “’It’s Constant Verbal Abuse’: San Francisco Bus Driver Recounts Assault after Enforcing Mask Rule.” The Guardian, 28 July 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jul/27/san-francisco-bus-driver-assaulted-mask-rule

“Employed Persons by Detailed Industry, Sex, Race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 22 Jan. 202., www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.htm

Gonnerman, Jennifer. “A Transit Worker’s Survival Story.” The New Yorker, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/08/31/a-transit-workers-survival-story

“Not-So-Good Vibrations: Is Hand-Arm Vibration Syndrome (HAVS) In Your Future?” Jobsite, 9 Jan. 2018, www.procore.com/jobsite/not-so-good-vibrations-is-hand-arm-vibration-syndrome-havs-in-your-future/

“Transit Advisory Committee for Safety (TRACS) 14‐01 Report.” Federal Transit Administration. 6 July, 2015. https://www.transit.dot.gov/sites/fta.dot.gov/files/Final_TRACS_Assaults_Report_14-01_07_06_15_pdf_rv6.pdf

Walker, Alissa. “Coronavirus Is Not Fuel for Urbanist Fantasies.” Curbed, Curbed, 20 May 2020. www.curbed.com/2020/5/20/21263319/coronavirus-future-city-urban-covid-19