The reflection of medicine in the universal arts has both intrigued and captivated the medical profession for centuries. This attraction has motivated several rheumatologists to look at catalogues and reproductions of paintings with a magnifying glass, trying to discover features of rheumatic diseases depicted by artists long before these diseases were defined as specific pathologic entities. Although a work of art may provide evidence of ancient disease, the interpretation may be difficult, leading to errors in diagnosis due to misinterpretation of the artistic convention or technique [ 1 ]. The accurate diagnosis of rheumatic diseases that are portrayed in the visual arts therefore requires tracing the historical background of the piece of art.

Evidence of rheumatic diseases in history dates from 1279 BC, during the reign of Ramses II. A retrospective radiologic analysis of his mummy showed severe changes associated with SpA, with post-inflammatory hip arthritis and cervical ankylosis [ 2 ]. Moreover, evidence of the origin of RA in ∼1400 AD (and not in 1800 AD, as previously thought) stimulated certain experts to look for traces of this disease before that time. These experts identified paintings that date from 1400 to 1600 AD and that depict hand changes suggestive of RA. It was in 1853 AD when the term progressive articular rheumatism was described in Charcot’s thesis, and later, in 1859 AD, Sir Alfred Baring Garrod adopted the term RA [ 3–5 ]. This anecdote shows the delay in finding pictorial and scientific evidence of the disease.

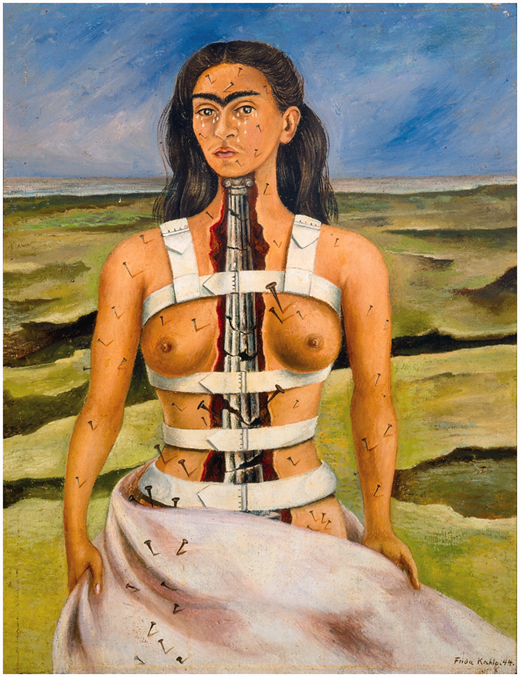

Discovering evidence of rheumatic diseases in the visual arts raises the questions of whether the artist reflected what surrounded him in a realistic fashion or suffered from the disease himself and, in the latter case, how the illness influenced his art. It is clear that art reflects every moment of human thought, influenced by the historical backdrop. For example, in the 14th century, master painters searched for perfection in human anatomy, whereas artists from the 20th century created realities reflective more of their own inner visions than what lay before them in nature. As a result, 20th century painting movements and trends inspired artists to set out in many divergent directions [ 6 ]. Painters and sculptors have long been recognized as professionally prone to conditions such as lead intoxication and stone dust silicone exposition, although the mean age at death for artists has been described as higher than that of the general population [ 4 ].

The artist and the rheumatologist’s perspective converged in Andreas Vesalius, a brilliant anatomist of the 1500s with a remarkable practical skill in dissecting bodies, and the author of De Humani Corporis Fabrica. He served as imperial physician at the court of Emperor Charles V and during that time he treated injuries from battle and tournaments, but most important, he treated Charles V, who was affected by gout [ 7 , 8 ]. The common situation in which the artist and rheumatologist collide as both spectator and patient is the focus of this review.

Overview

This study takes a look at some of the depictions in historical art of painful diseases and hand impairments that changed the way an artist created their work. There are clear delineations between the works of a health hand and those of a diseased hand, as evidenced in the work of Paul Klee. Even before there were clinical terms for these ailments, humans have been suffering from the pain and difficultly of impaired hands. The need for helpful solutions has been evident for thousands of years, and though designers have brought some relief, there is still so much room for opportunity to help.