This article, although only one study, proposes the potential significance a child’s environment can have on their learning. Although based in the classroom and not at home, it provides a good framework through which to look at the impact of the built environment on learning.

—

Barrett, Peter, et al. “A Holistic, Multi-level Analysis Identifying the Impact of Classroom Design on Pupils’ Learning.” Building and Environment, vol. 59, Jan 2013, pp. 678-689, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2012.09.016. Accessed 1 Sept 2020.

Introduction

“The multi-sensory impact of built environments on humans is a complex and current issue. . . Within the challenging context, this study set out to take a multi-dimesional, holistic view of the built environment within which humans (pupils in this case) live and work (study in this case) and sought to discover and explain the impacts on human well-being and performance (improved learning in this case).

“The main aim of this study was ‘to explore if there is any evidence for demonstrable impacts of school building design on the learning rates of pupils in primary schools.’

Theoretical Approach

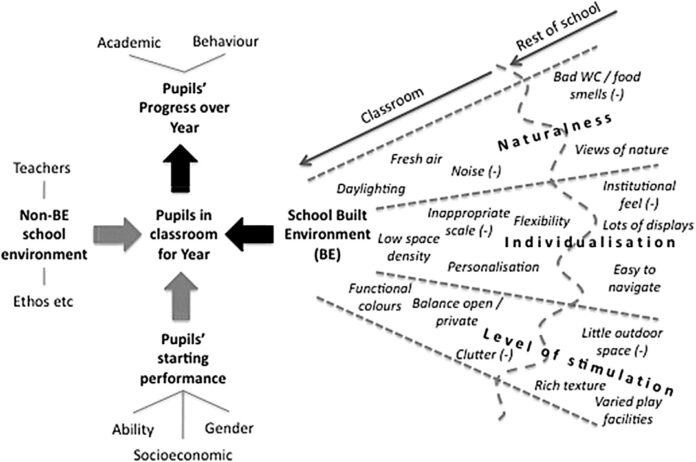

“A holistic perspective of the multi-sensory impacts of the built environment was operationalised via the hypothesis that the characteristics of the brain’s functioning in synthesising sensory inputs highlights the importance of three broad design principles

concerning our environment, namely: naturalness, individualisation and the appropriate level of stimulation

See full article for Methods and Results sections of the study.

Discussion

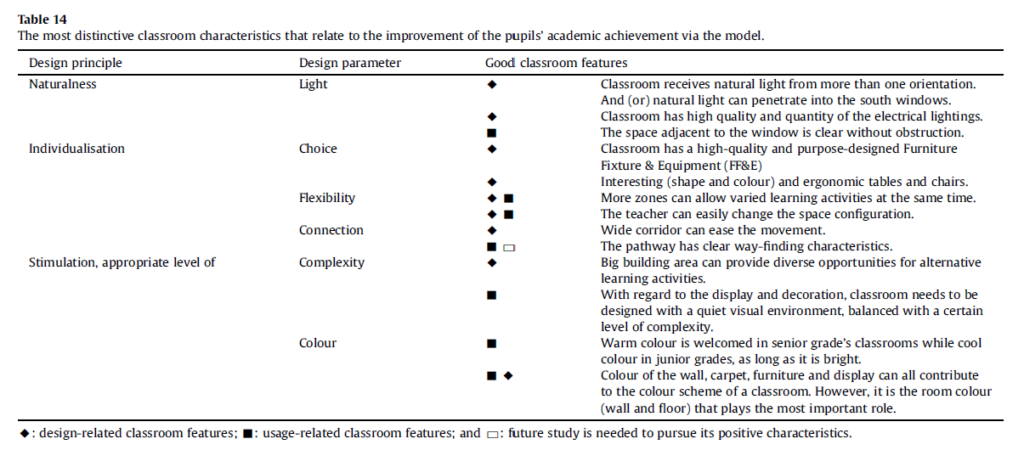

“Six of the 10 built environment “design parameters” were identified as being particularly influential in the multi-level linear regression model. Taken together these have been shown to significantly influence pupil progression and to account for a large part of the variability in pupil performance at the class level. The six parameters are colour, choice, connection, complexity, flexibility and light.

Conclusion

“A range of hypotheses was tested using data on 751 pupils from 34 classrooms in seven schools. Clear impacts on learning progression by a range of environmental design parameters have been identified, using multi-level statistical analysis. . .

“It should be remembered that the spaces have been assessed in functional terms, focusing entirely on the impact of the differences between spaces on the academic performance of the pupils. In this context it can be seen that parameters to do with the design principle of “individualisation” are prominent. Here the issue of connection has raised some surprising issues compared with prevalent theory, but these can be seen to make sense if a pupil’s perspective is taken. Achieving the “appropriate level of stimulation” for learning is also important and raises the issue of functional requirements versus aesthetic preferences. So young children may like exciting spaces, but to learn it would seem they need relatively ordered spaces, but with a reasonable degree of interest. In the area of “naturalness”, only the parameter of light remained in the equation, and even this was quite a complex relationship between a desire for light, a dislike of glare and the importance of good artificial lighting. . .

“Given the size of the challenge as indicated in Section 1, it is a significant step that a hypothesis-led, multi-level model that explains 51% of the variation in pupil learning has been successfully developed.”