by: Leanne E. Atwater, Allison M. Tringale, Rachel E. Sturm, Scott N. Taylor, and Phillip W. Braddy

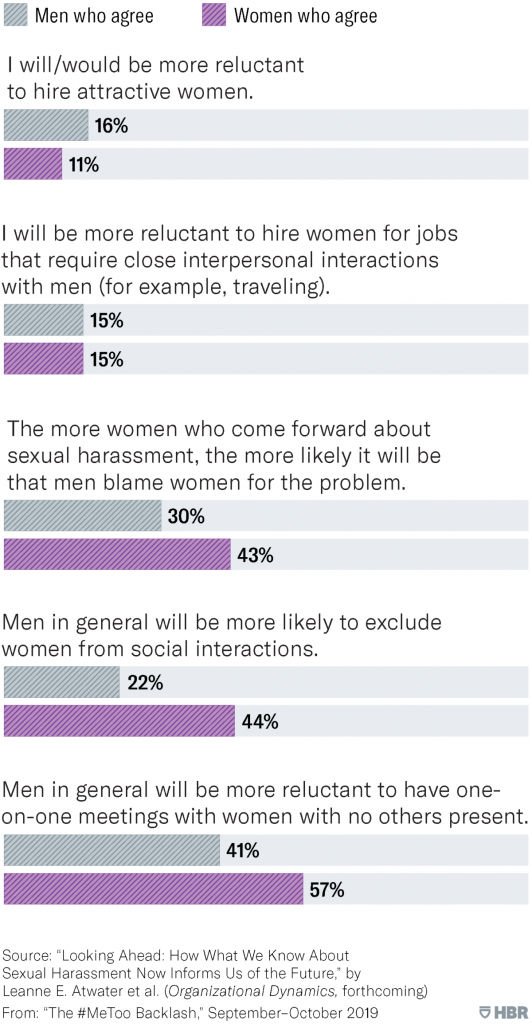

In the fall of 2017, when the New York Times and other media began reporting on widespread sexual harassment and assault by powerful male entertainment figures, many people were heartened. The conventional wisdom was that bringing the issue to light and punishing those responsible would have a deterrent effect. Leanne Atwater, a management professor at the University of Houston, had a different response. “Most of the reaction to #MeToo was celebratory; it assumed women were really going to benefit,” she says. But she and her research colleagues were skeptical. “We said, ‘We aren’t sure this is going to go as positively as people think—there may be some fallout.’”

In early 2018 the group began a study to determine whether their fears were founded. They created two surveys—one for men and one for women—and distributed them to workers in a wide range of industries, collecting data from 152 men and 303 women in all.

“Most men know what sexual harassment is, and most women know what it is,” Atwater says. “The idea that men don’t know their behavior is bad and that women are making a mountain out of a molehill is largely untrue. If anything, women are more lenient in defining harassment.”

Next the researchers explored the incidence of harassment in the workplace. Sixty-three percent of women reported having been harassed, with 33% experiencing it more than once. A woman’s age, the supervisor’s gender, whether the woman filled a blue-collar or a white-collar role, and whether she was married had no bearing on the likelihood that she had been harassed. Just 20% of women who had been harassed reported the episode; among those who didn’t, the chief deterrents were fear of negative consequences and apprehension that they would be labeled troublemakers. Five percent of men admitted to having harassed a colleague, and another 20% said that “maybe” they had done so.

The researchers have several recommendations for organizations looking to reduce harassment, a number of which involve prevention training. Their study shows that traditional sexual harassment training has little effect, perhaps because much of it focuses on helping employees understand what constitutes harassment, and the data shows they already do. Instead, the researchers say, companies should implement training that educates employees about sexism and character. Their data shows that employees who display high levels of sexism are more likely to engage in negative behaviors, and they believe training can reduce those levels. Their data also shows that people of high character—those who display virtues such as courage—are less likely to harass and more likely to intervene when others do. “Though character building in organizations is on the cutting edge and consultants are just learning how to do this, there are training resources available,” the researchers write.

This article highlights that initiatives that are made to benefit women can have major negative effects on them. In the case of #MeToo many men feel that it is better to protect themselves from potential allegations than making sure women get a fair chance. It continues to show that institutionalized sexisume continues to negatively impact women even when they are trying to make the world safer for themselves.

Originally Published By : Harvard Business Review