High blood pressure, also known as hypertension, is the leading global risk for death according to the World Health Organization [1]. One of the main contributing factors to this staggering statistic is that hypertension itself is asymptomatic in nearly all cases. In a clinical study in Denmark of a random sample of adults aged 60-74, researchers found that only 21 percent knew that hypertension can occur without symptoms [2]. This is especially concerning because risk of hypertension increases as you age. Without physical symptoms, diagnosing and managing high blood pressure is very challenging. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention found that only one in four hypertensive adults in the US have their condition under control [3]. The prevention and management of hypertension is a multifaceted problem that has many contributing factors, some of which foster greater collective awareness than others.

Some of the more well-known factors include age, genetics, diet, and weight. In a randomized, anonymous blood pressure literacy survey I conducted, nearly 100 percent of the 124 subjects identified these as being risk factors for high blood pressure. Contrarily, less than 50 percent selected the three other risk factors I had listed: condition of kidneys, water volume, and levels of various hormones in the body. This suggests that there is a rather good amount of widespread knowledge on certain factors, while others lack the same breadth of outreach.

As mentioned, genetics are a widely recognized risk factor. Hypertension having a genetic component allows people who are aware of their family history the opportunity to adopt preventative methods in order to decrease their already heightened risk of hypertension. Additionally, diet and weight are other physical factors that the majority recognized. People’s weight is relative to their exercise habits: another blood pressure factor. Those who live a sedentary lifestyle are more likely to be overweight and thus are at a higher risk for adopting hypertension. Inversely, those that are active and exercise their heart through activity, decrease their risk of hypertension. Other factors such as condition of kidneys, hormone levels, and water volume were less likely to be identified by survey participants suggesting the public education around hypertension prevention is not as centralized on these factors.

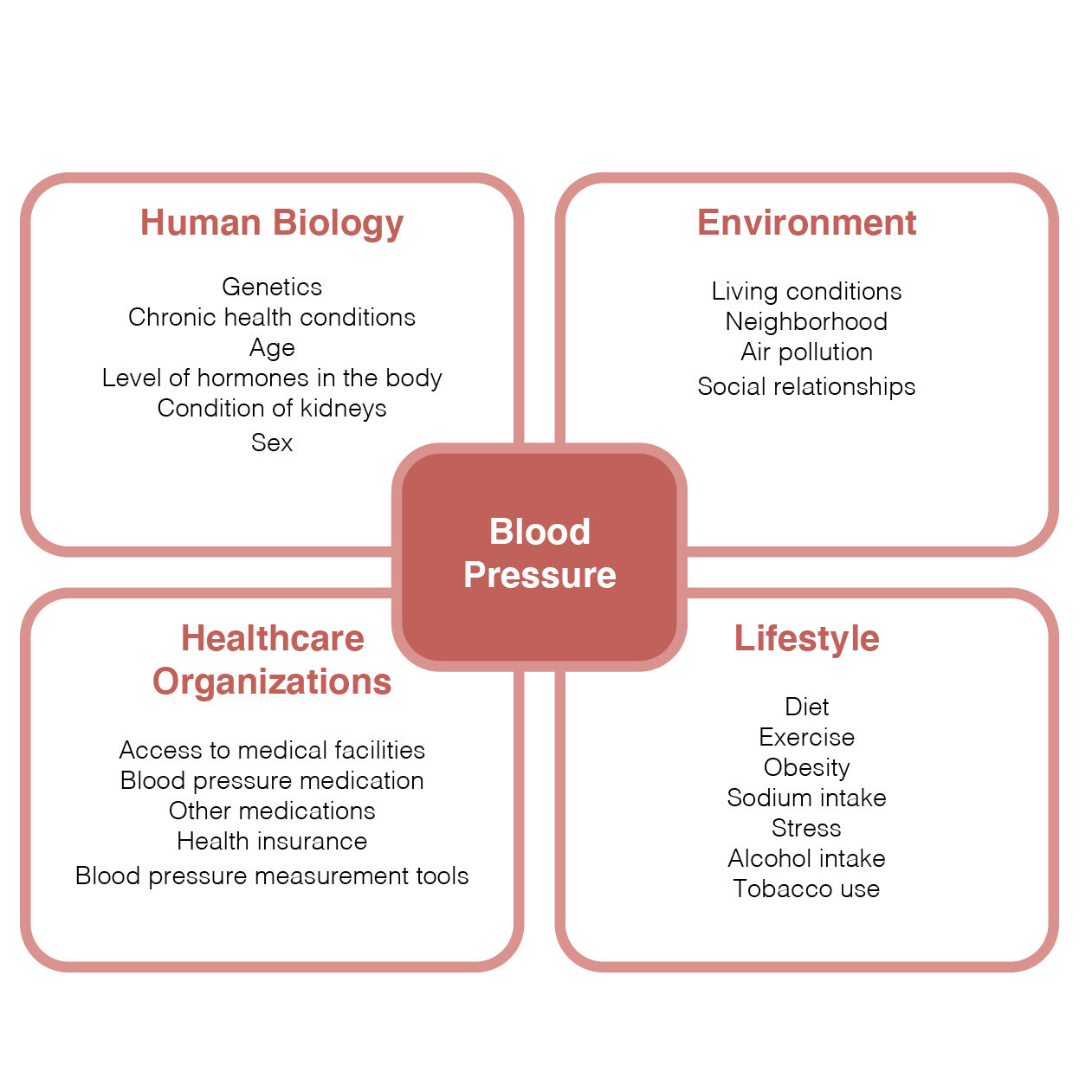

Although these factors are all mostly physical, other external ones are of equal importance when determining risks for hypertension. The Lalonde Report, developed by Marc Lalonde is composed of interdependent quadrants that all affect an individual’s health: human biology, environment, health care organizations and lifestyle. Below is a Lalonde Report populated with hypertension risk factors.

As defined by Lalonde, human biology is the physical and mental aspects of a human. This is where genetics, age, and other physical conditions fall in relation to the human biology of one’s blood pressure. In contrast, the environment is anything external to an individual. In this quadrant would be where an individual lives and their social experiences. Urban design research studies show that wealthier areas are more likely to have thoughtful and well-kept architecture, greater exposure to greenery, and emit higher levels of safety and security. This relates to heart health because people in these areas are more likely to walk more often and spend more time outdoors in response to these elements. However, due to socio-economic levels, people may not be able to afford to move to places where these elements are prevalent. This is inversely true for low-income neighborhoods. From a security perspective, feelings of safety decrease in low-income neighborhoods. In response, there is a reduced desire or ability to spend time outside. This decreases physical activity opportunities for those living in low-income neighborhoods [4]. A lower sense of security may also raise stress which is another factor for blood pressure health.

The healthcare organizations quadrant is where the access and equality for ways to measure blood pressure (both at home and at a medical facility), hypertension medicine, medical care, and health insurance fall. Someone who has health insurance has a greater chance of visiting a doctor more regularly than someone without insurance. For most people, the doctor’s office is the only place they have their blood pressure measured. This makes the likelihood of identifying high blood pressure greater for those who go to a doctor more often. Also, the cost of hypertension medication impacts blood pressure regulation. Those who can not afford medication, may choose not to take it, even if prescribed by a doctor, ultimately increasing their risk of hypertension related diseases or events.

The last quadrant is lifestyle. These are elements that are typically easier to be controlled than others. It is where diet and exercise fall. However, external items such as socioeconomic level and disability may impact the ability to control lifestyle factors. We can look back to the exercise and neighborhood wealth relationship described above for an example of this. Just like the quadrants are interdependent, all of the factors are as well.

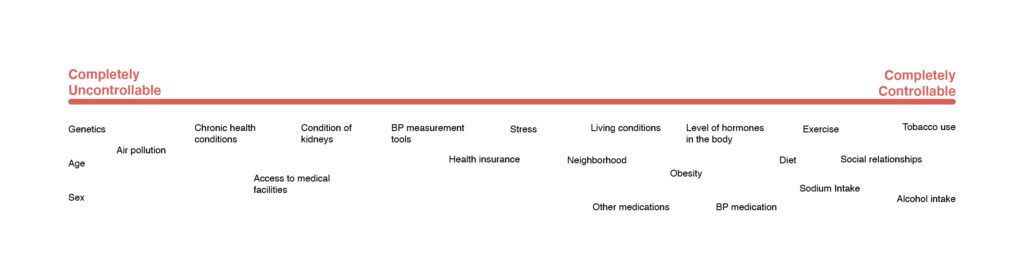

The Lalonde Report above displays the overwhelming amount of contributors that can affect heart health. However, the different abilities to control some of these factors eases the digestion of its vastness. For example, although we cannot control our genetics, we can decrease the number of hours a day we are sedentary. Or if exercise is not a feasible option, we can eat healthier and watch our sodium intake. While we may not be able to account for all factors, controlling some of them is progress towards prevention. Figure 2 displays perceived controllability of the many factors discussed that contribute to increased blood pressure.

In sum, these factors are not independent of each other. For example, although you may be able to control your diet, you still can be of an age that puts you at higher risk. The intertwinement of all these components advocates for broader education of risk factors and ultimately, widespread healthy changes of controllable factors.

As identified thus far, there is a staggering number of factors that impact one’s risk of hypertension. This, accompanied by hypertension’s contribution to heart related diseases, events, and mortality, can make the topic intense and difficult to fully comprehend. I have briefly touched on the complexities and profusion of elements that contribute to high blood pressure, so it is understandable that many people may feel overwhelmed when discussing the topic.

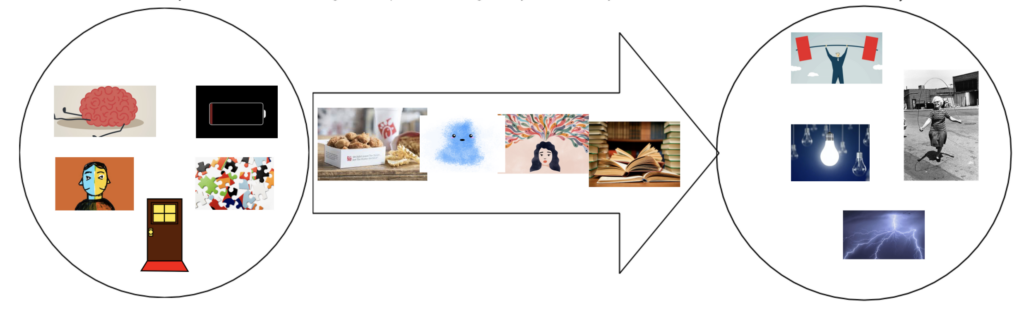

To better understand the feelings associated with personal heart health, I conducted a co-design activity. I asked individuals to use pictures to describe their feelings associated with their heart health. An example of a participant’s final model is below.

The circle on the left represents how the individual currently feels about their heart health while the circle on the right is how they want to feel about their heart health. The arrow in the middle is used to show feelings associated with whatever is keeping individuals from reaching their goal attitude towards personal heart health. All participants said they felt overwhelmed about their current heart health and described a desire to change this feeling. Many associated their current feelings with anxiety and one said they “don’t even know where to begin”.

In addition to the co-design responses, those I interviewed also shared feelings of apprehension and discouragement due to the profoundness of the topic. Some even said they prefer to avoid measuring their own and reading about it because they are too scared of what may come of their results. One used the phrase “ignorance is bliss” when describing her avoidance. This addresses an important ethical dilemma of blood pressure education.

In some instances, people may prefer to take the “ignorance is bliss” approach to heart health. For many, knowing that they are at high risk may stress them out more, only decreasing heart health and overall mental health. Should increasing blood pressure literacy be a personal choice? Public interventions or education may expand the transparency of the severity and recommended actions to prevent hypertension. However, this transparency could lead to more personal negative responses to the newly acquired knowledge. This ethical dilemma is something to consider when looking at this problem from a public health lens.

When diagnosed with hypertension, patients often receive pamphlets with preventative strategies accompanied with little guidance on how to digest the diagnosis and how to adapt the suggested lifestyle changes. Additionally, 21 percent of the US population is illiterate making these pamphlets impractical for one fifth of the population [5]. Overall, the existing educational tools for public hypertension prevention and management are inadequate and inaccessible.

In addition to a need for appropriate educational tools for prevention, there are also many gaps within existing measurement methods. The traditional blood pressure cuff has a substantial amount of usability and technical flaws. This is apparent for cuffs intended for at-home use as well as professional setting use. There is inconsistency in readings, vague instructions, minimal room for placement error, and poor communication of results. Despite its flaws, there has been little modification of the design besides minor technological improvements. However, the cuff itself and its inconvenience seemed to be the most pressing issue for those I talked to. Many validated the other flaws listed above, but found the greatest annoyance in having to remember to get the cuff out and use it as often as they should. Two interviewees specifically said that if the device was better incorporated or built into their daily routine, they would utilize it more. Is there more potential for a device that is seamlessly integrated into lifestyles?

Further, the personal at-home cuffs lack accessibility because they cost money, demand literacy, require baseline knowledge for understanding the results, and depend on a steep usability learning curve.

From risk factors, to health literacy, to measurement methods, there are clear gaps within how the US and individuals personally understand and address high blood pressure. As exemplified throughout this analysis, there are many layers and contributing elements that impact this problem space. In a space that is typically filled with medical professionals, public health experts, and biomedical engineers, addressing it from a design perspective may seem initially impractical and rudimentary. However, the complexities addressed here have clear potential for design intervention. Blood pressure reaches beyond physical health. It is impacted by social and environmental factors, both of which design has great opportunity to intervene.

Works Cited

[1] Global Health Risks Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. 2009.

[2] Qvist, Ina, et al. “Self-Reported Knowledge and Awareness about Blood Pressure and Hypertension: a Cross-Sectional Study of a Random Sample of Men and Women Aged 60-74 Years.” Clinical Epidemiology, Dove Medical Press, 15 Feb. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3933349/.

[3] “Facts About Hypertension.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 8 Sept. 2020, www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm.

[4] Qvist, Ina, et al. “Self-Reported Knowledge and Awareness about Blood Pressure and Hypertension: a Cross-Sectional Study of a Random Sample of Men and Women Aged 60-74 Years.” Clinical Epidemiology, Dove Medical Press, 15 Feb. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3933349/.

[5] Rea, Amy. “How Serious Is America’s Literacy Problem?” Library Journal, www.libraryjournal.com/?detailStory=How-Serious-Is-Americas-Literacy-Problem.