It’s hard to deny that subscription services are attached to financial wellness as they increasingly become unavoidable, existing in almost every aspect of our lives and beginning to seep into the few ones they haven’t. From the promised convenience that burned quickly with streaming platforms to the ones that exemplify over-consumption like themed collection boxes, our relationship with subscription services has caused a drastic change in consumers’ sense of direction, and control over their decisions. In short, “We’re stuck in a subscription payment hamster wheel” (Westenberg, 2023). Now more than ever, people are beginning to feel the impact this has on financial stability and believe it’s time to reassess how these services affect personal finance and well-being.

To better understand the depths of subscription services’ impact, I first had to define the surge of when this economy came to be. I found that “the subscription economy has grown over 435% in 9 years” (“The Future of Subscriptions,” 2024).

As for what is driving the rise, according to ZNet, people want to own less stuff, and subscriptions alleviate this burden of ownership; therefore “more and more industries around the world are adopting subscription business models, and people are ready for them. Internationally, 74 percent of adults believe that subscription models are the wave of the future” (“The Subscription Economy and the End of Ownership,” 2023). I see this to be a misjudgment of their statistics, for people saying they think subscriptions are the future does not equate to them being ready for them. You can believe this to be the case, and still feel unprepared, as many do in the current state of subscriptions.

This little tangent I went over in my head led me down a path of further discovery into what would become the basis of my focus.

There is a misalignment between consumer needs and business motivations. While consumers may rely on a sense of convenience to counteract how subscriptions undermine their financial flexibility, businesses are propelled with predictable, recurring revenue and locked-in loyalty. As the lines begin to blur where ownership lies, designers have the unique opportunity to approach this situation at the convergence of consumer and business interests.

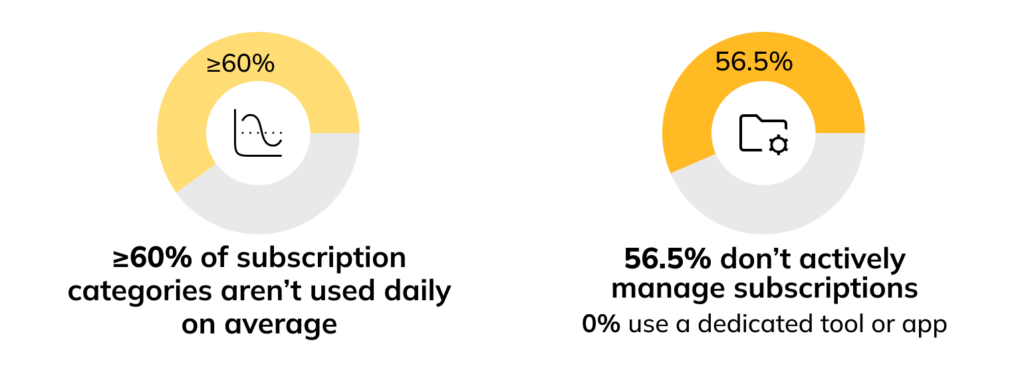

This begins with addressing the impact subscription services have on financial well-being. Views among consumers differ from recognizing the convenience that can still exist in mild consumption to the belief that that convenience has completely eroded. Where they and many others agree, is that the promised convenience subscription models originally offered are not sustainable. It is referred to once even as a trap, as the amounting financial commitments we make limit our choice over the content we watch to the content we have. It diminishes our flexibility and encourages over-consumption to truly have control over all our options, or even just access to them. As one article puts it, “Our paychecks are eaten away in advance before we realize how many 30-day free trials and monthly tithes we’ve committed ourselves to” (Westenberg, 2023). This mentality often results in consumers paying for more than they use, with one example spending over $1000 on subscriptions they don’t need (Walden, 2020). My research corroborates this lack of management and the concept of services going unused:

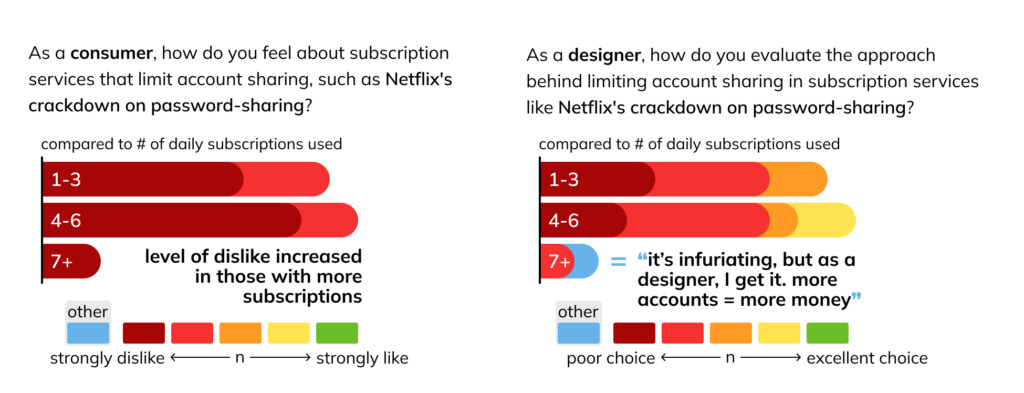

I specifically surveyed fourth-year design students, for they are just starting to get real-world experience balancing the needs of consumers and businesses. I asked them about Netflix’s crackdown on password sharing and how their views differed when thinking of it as a consumer versus a designer:

The more subscriptions people used, the stronger their dislike tended to be towards this strategy employed by Netflix. What I found interesting from this was how the trend flipped when thinking of it as a designer. Those who used more subscriptions were more likely to see the value in this tactic from the business perspective, even if they were the most to dislike it. If designers can recognize this imbalance as suitable for businesses, but detrimental to consumers, would they still employ this strategy if it were up to them?

This leads me to the root of the cause, which is humans are the problem, not the holistic businesses I generalize as entities or the technology that fuels this system. There is a dichotomy in designers that recounts our own combative needs, and it exists elsewhere in the subscription world where one entity can both promote the downfall of subscriptions while feeding into the system. To support this, I collected some screenshots from articles that think negatively of subscriptions, but in order to read them, you first need to subscribe:

I felt specifically misled by the Medium article, as it told me I only had to make an account to read the story, but then once I made an account, I had to upgrade that account and pay at least $5 a month to hear about how subscriptions are a trap. I think I learned my lesson without the read. This disconnect between consumers and businesses can be found in our discussions of such. In a similar vein, we become both the defender and opposition of this system when we continuously pay monthly for services we don’t want, creating a false perception of customer loyalty.

This plays out in the example of ownership. Are people through with owning things if they buy into subscriptions, or could they still “miss the days when the tools felt like mine, not someone else’s borrowed goods”? (Westenberg, 2023). I would argue these services don’t take ownership away, they just reposition it in a manner that causes confusion over control, cornering some people in through a lack of alternatives and allowing others to surmise that this move is the consensus wanted. When thinking of the articles I had to buy into to read, I no longer had control over my options to read freely, instead, I needed to own three subscriptions. Doing so would not only give the business the assumption I support this model as I become a number they can charge, but it also lessens the true needs I originally had as a consumer, which was to inform myself with a reading. To test this theory of ownership existing in subscriptions, I looked back to my survey and found that 72.7% of participants continue paying based on the fear of losing content. Why would you fear losing something if you don’t have it?

These blurring lines of ownership are part of the miscommunication between consumer and business motivations, where consumers begin to feel the inconvenience of subscriptions. When surveyed about what factors they think subscription services rely on most to keep customers subscribed, the top two recurring answers were reliance on essential features and lack of alternatives; the least common answer was user experience or cost-effectiveness. To a designer, human-centric strategies were perceived as less valuable to businesses. Equally, consumers can mislead businesses to believe they’ve achieved customer loyalty even if it is done through methods they’d protest. I asked my participants about this, and here was how they defined loyalty being built:

Though most people feel loyal to subscriptions, how that loyalty is achieved is not seen in a positive light. To me, this begins with dark tactics like the Medium article that misled me into thinking I don’t have to pay to read it. This doesn’t seem to be a rare occurrence: “In an analysis of 642 websites and apps offering subscription services, the study found that the majority (nearly 76%) used at least one dark pattern and nearly 67% used more than one” (Perez, 2024).

Reflecting on how many designers expressed frustration with the password-sharing crackdown by companies like Netflix, yet acknowledged that such measures are beneficial from a business standpoint, is the same to be said of dark tactics? How else would these dark tactics make it into subscriptions? “A human made the decision to say, ‘I have a choice between right and wrong. And I’m choosing wrong. The technology just made it easier for them to accept what they thought: that they weren’t causing direct harm.’” (Monty, 2019)

There’s a need for clarity, whether it’s from the finances that secretly pile up and dictate our future, or among the differing motivations of consumers and businesses that blur ownership. “Banks and fintech companies should focus on helping consumers fight back.” (Johnson, 2024). My goal is not to dismantle the hamster wheel people individually live in, for that is not my decision and would only be counter-intuitive to bringing back choice. What I can do is offer a picture of that hamster wheel, as it can be a conduit to change, or at the very least offer awareness to continue spending this way.

It’s not just about creating a subscription command center though. That’s not the root of the problem, and each person’s spending habits are different. Perhaps, on an individual level, our recurring payments in frequent categories can be marketed as forms of subscriptions. In a way, when you spend 10 bucks every month for the same cleanser, it sort of is. Giving clarity back to consumers on how they spend their money will address the concern of over-compensation and allow for a personalized awareness of how we control these services. With an app that is a banking tool to categorize spending by interests, we begin to rethink ownership in a way that gives choice back to consumers. I’ve drawn out this concept more in a design conjecture entitled Comfort Zone/Pathways:

With this concept, I started to question how the value of exchange can still exist without the use of dark tactics. Leaning towards the business side, I thought of app integration and how banks could get a cut from subscriptions run through their system, and how this can then, in turn, manage the consumer problem of how over-consumption is easily ignored through the fragmentation of content between platforms. By creating a hub that is almost a Google for what you have, it provides clarity over what you own. Each subscription can then be leveraged to the individual’s specific needs, which would support their financial wellness and address the hidden costs we don’t utilize. I’ve drawn out this concept further in a second design conjecture entitled Lifestyle Command Center:

With these two ideas, I lean toward personalization, but there is also a concern for balancing it. On one side, “Consumers have witnessed mass-personalisation through many of their digital experiences – think Netflix suggestions and Spotify personalised playlists. They will now expect the same from their financial services” (Pollari et al., 2019). The other concern is I need to be aware of what “theorist Nick Srnicek calls ’platform capitalism,’ where algorithms that feed on user information take decision-making out of our hands entirely” (Naraharisetty, 2022). Personalization has to be used as much as it is warranted, not because it is the expectation. The first conjecture puts personalization in the hands of consumers to form a new way of thinking about subscriptions; the second creates a personalized support system. Both of these examples address the loss of control when we are limited to the content we have, and so they should also reflect on the possibilities new discoveries could bring.

All of this to say, the rapid increase in subscription services is reflected in our prospects being limited. Whether it is the content we watch or the articles we try to read, the promise of efficiency falters under the reality of recurring payments and the lack of alternative options. It becomes unclear what we own, but very obvious what we don’t have. Our sense of control over the future is tested, and our well-being is affected when motivations between consumers and businesses are unbalanced. It is our own creation and miscommunication that creates this opportunity for designers to shift the narrative of transparency, where loyalty is achieved through the alignment of our shared goals. It’s not about getting off the hamster wheel, but getting in tune with the fact that there’s a reason for the cycle. What this reason is and how it affects your pace is defined by you.

References

Johnson, A. (2024, January 26). Save Me From The Subscription Economy!. FinTech Takes. https://fintechtakes.com/articles/2024-01-26/subscription-economy/

Monty, S. (2019, March 21). Lessons from The Brain Center at Whipple’s. Timeless Leadership. https://www.timelesstimely.com/p/lessons-from-the-brain-center-at

Naraharisetty, R. (2022, September 23). How Streaming Turned Art into Content, and People into Consumers. The Swaddle. https://www.theswaddle.com/how-streaming-turned-art-into-content-and-people-into-consumers

OpenAI. (2024). ChatGPT (Sept 2024 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

Perez, S. (2024, July 10). FTC study finds ‘dark patterns’ used by a majority of subscription apps and websites. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2024/07/10/ftc-study-finds-dark-patterns-used-by-a-majority-of-subscription-apps-and-websites/?guccounter=1

Pollari, I., Bekker, C., & Jowell, C. (2019). The future of digital banking in 2030. KPMG. https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/ua/pdf/2019/09/future-of-digital-banking-in-2030-cba.pd.pdf

The Future of Subscriptions. Zuora. (2024, February 26). https://www.zuora.com/guides/the-future-of-subscriptions/

The Subscription Economy and the End of Ownership. Washington State University Carson College of Business. (2023). https://onlinemba.wsu.edu/blog/the-subscription-economy-and-the-end-of-ownership

Walden, J. (2020, February 10). Are Subscription Services Quietly Destroying Financial Wellness?. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/subscription-services-quietly-destroying-financial-wellness-/

Westenberg, J. (2023, October 15). The Subscription Economy Sucks. Medium. https://joanwestenberg.medium.com/the-subscription-economy-sucks-5324f402491a