Photo credit: Elise Aultman

Humans are a disease and we’re killing the Earth. Every day we cut down acres of trees to make paper, burn tons of coal to fuel furnaces, and suck out barrels of oil from the ground to fuel our cars. We fight wars over land, bombing and looting and killing to claim what we think should be ours. We’re a disease. We hunt animals, for furs, meats, and sometimes just for fun, and cause once flourishing populations to go extinct. Our trash ends up wrapped around sea turtles’ necks, chemicals are dumped into oceans and rivers, and smog covers our cities. We’re killing the Earth and we can’t seem to stop. We’re a disease and we keep spreading. The Earth would be better off without us, why don’t we just let ourselves die out and it can return to its natural beauty…

If you’re anything like me, reading this feels demoralizing. Even though humans aren’t a disease to Earth, hearing the sentiment repeated over and over almost makes me believe it. No matter how much I want to stay positive, it’s hard to recognize that these statements are untrue when feel demoralized.

Fortunately, there is no “untouched” world and there never has been. Beings of all species interact with their environment, that’s just what it means to be alive. In fact, the myth of a pure, natural world is a relatively new concept. Claudia Geib, an environmental journalist for the anthropology magazine SAPIENS, traces it back to the term terra nullius, which was first used by Pope Urban II in 1095 to describe “the idea that any non-Christian land is a blank slate for the taking,” (Geib, 2022, para. 11). For the next 1,000 years, terra nullius would be used to justify western colonization. In the United States, early colonizers saw the land, decided it was “untouched” (unchristian), and claimed it as their new “pristine” territory. As the U.S. continued to grow, this same idea justified westward expansion by dehumanizing indigenous people. Ecologist Erle Ellis summarizes the “pristine” land phenomenon as follows, “Within the pristine myth, [these] people don’t have agency, and that’s pretty important to the whole concept” of that myth,” since non-Christians and non-westerners had no agency and were therefore not people, their land was free for the taking without guilt (para. 12).

So, how do we grapple with this as Americans in 2024? How does our government perceive the land we live on? What are they doing to take care of it? There are a million places to start, I started by visiting ODNR—as the state’s environmental department, they would have something interesting to say. What I discovered is that ODNR has a complicated relationship with the land. As a government institution, they are subject to organizational change and workplace culture shifts as new politicians are elected. Therefore, they can’t risk being too conservative or too liberal, they have to strike a careful balance. During my first meeting with our ODNR partners, they explained that their approach to sustainability is through small initiatives that can be implemented at the park-level. They have some small-scale sustainability initiatives like fishing line waste bins, but there are bigger issues they wish they could address like visitor litter, companies dumping waste, environmental conservation, erosion, and the list goes on. Unfortunately, since these issues require more time, money, and are deemed more controversial they are less likely to come to fruition.

Since much of ODNR’s work is influenced by things beyond their control I wondered if there was a way we could spark change in attitudes toward ODNR parks. Could something as simple as a shaded trash can be an incentive for visitors to throw out their trash in sunny parks? Would a respite from the sun be enough to make people want to throw out their trash? Would it be enough to make the cost of building the shade structure worthwhile?

Science & Tech Design Conjecture

Maybe in some parks a similar idea could work, but this conjecture makes clear that even something as simple as a shaded trashcan is not actually that simple. This conjecture relies on changing factors like weather (is it cloudy?), angle of sun (is it low in the sky), and the assumption that people want to be shaded. Realistically, all of these factors are hard to account for. So what now?

This conjecture highlights the need for designs to motivate individuals on a personal level and to learn about ODNR park visitors, I visited some parks. I conducted 3 visits to ODNR sites: AW Marion State Park, Deer Creek State Park, and the Antrim Lake fishing dock. AW Marion and Deer Creek are located about 40-50 minutes outside of Ohio in rural areas, situated in the middle of farmland and villages scattered along the roads. Though I have never lived in a rural community, many members of my family have. When I visit them in rural Ohio I’m struck by how isolated I feel. While I am used to the vast social networks of suburban and urban life, rural life isn’t quite as varied. People attend the same church for decades years, plow the same soil for generations, do the same activities, and talk to the same people. While talking to family from rural areas, I noticed that they are often wary of “new ideas” or perceived changes because they challenge this more conservative lifestyle. This is often the case with sustainability efforts, for example, my grandma hates windmills with a burning passion!

This is where the term “sustainability” becomes an issue. “Sustainability” as a term regarding social movements was formally recognized in the 1970s (Umich.edu), therefore, it’s a relatively new movement. However, rural communities are already participating in sustainable behaviors, that’s just not their main purpose. What would happen if the sustinability movements recognized this? Maybe people would find they have more in common than they thought. This is where the album Roots is relevant. This intertwining familiar stories with the daunting idea of sustainability could help people understand that sustainably is already a part of their lives, whether or not they use the term, and could lay the foundation for collaboration between ODNR park and the rural communities surrounding their parks.

Arts Design Conjecture

As I reflected on this conjecture, I can to the conclusion that targeting rural communities using stereotypes about what kinds of music they prefer is not perhaps, the most ethical or respectable approach. So if I can’t target people based on demographics like location to motivate them, how else can I motivation. That’s where Falk’s 5 Museum Archetypes come into play.

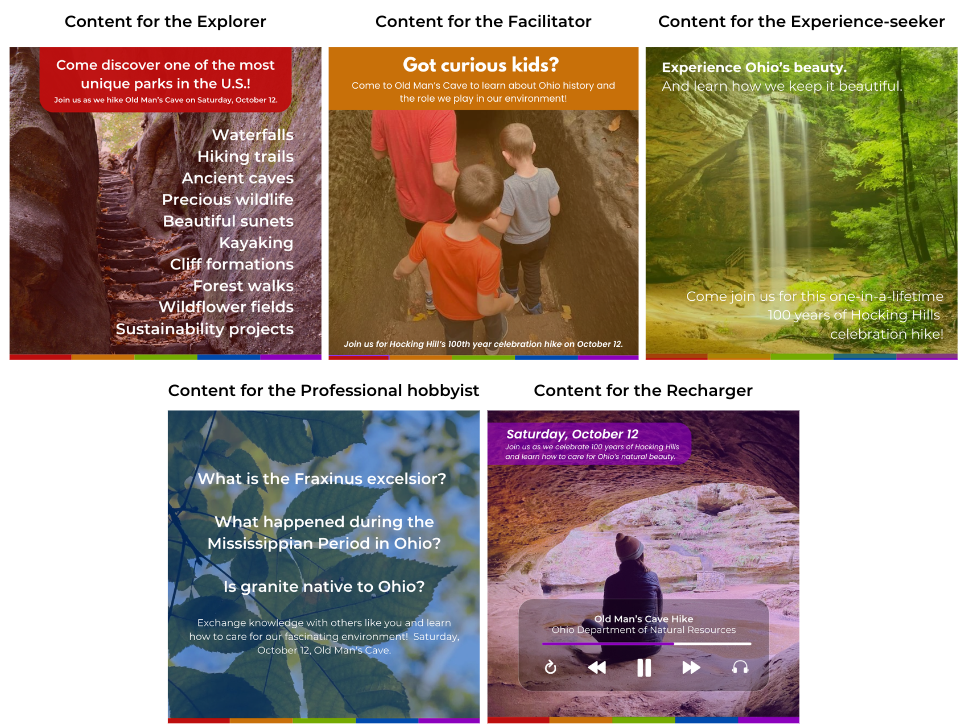

Visitors engage with environments based on their emotional and motivational needs. Therefore, it’s imperative that any designer who wants to change behavior must first understand motivation. Falk’s 5 Museum Visitor Archetypes (click here for lit review) inspired me to look beyond demographic generalizations in my next design conjectures. The five archetypes—are Explorer, Facilitator, Experience-seeker, Professional hobbyist, and Recharger—serve as tools for designers when trying to create solutions that resonate with a wide range of users (Christidou, 2010). To explore the limits of this tool, my Business Design Conjecture takes the five archetypes to the extreme. In this design conjecture, the five archetypes serve as the categories for five different types of social media feeds. Based on a user’s algorithm, the app will recommend one or two of the five archetypes accounts the user, the targeted posts motivating users to act according to the archetypes they most closely align with. Meeting users on their level, ODNR can more easily play to emotions and motivations associated with that archetype to change perceptions about sustainablity via posts, reels, stories, and other content.

Business Design Conjecture

At this point I knew that I should aim to motivate people, the question was how? What do people want? Money? Praise? I decided to survey one group of people who I know are notoriously active in sustainability movements: Unitarian Universalists. I hoped the survey could help me tease out what keeps them motivated, and perhaps provide some insight into ways of motiving people outside of Unitarian Universalism to get involved.

Survey infographic

What I found was that positive motivation, specifically motivation that sparked feelings of hope, was believed to be the best source of motivation, as chosen by the majority of individuals when asked to select from a list of possible motivators. Additionally, when asked to indicate how a series of images made them feel and how motivated they felt after viewing each image, positive images had a slightly high success rate than the negative ones. This is represented by the “Motivation scale” where Image 1 and Image 2 were phrased positively while Image 3 and Image 4 were phrased negatively. In future research.

Image 2 left, Image 3 right

All of this to say, my research has led me to two conclusions. One, if ODNR wants successful sustainability intitiatives they need to meet people at levels they, the people, can understand. And two, motivating people positively is likely to yield better results than motivating people negatively. Sustainability movements past and present, though well-intentioned, have negative consequences on people’s mental health that it detrimental to the cause in the long run. The sensationalization and politicization of these sustinability movements creates feelings of anxiety, guilt, helplessness, and anger as individuals struggle to navigate polarizing narratives surrounding environmental responsibility.

When someone isn’t familiar with sustinability, asking them to incorporating it into their behavior may feel like an unwanted burden, especially when it comes with charged, emotional baggage. Fortunately, sustinability doesn’t have be hard.

Given that many current sustainability movements are demoralizing and burdensome, there is a woefully untapped potential for hopeful and unifying movements. Therefore, ODNR should use design to bring visitors and nearby communities together with the goal of inspiring sustainable collective action. With the right tools, it can be accessible and rejuvenating instead of draining. With the help of ODNR, my senior capstone will reframe sustainability as a hopeful, unifying movement rather than a divisive one. I intend to collaborate with ODNR to spark change in a way that feels accessible, not overwhelming. With their expertise and my skillset, we can turn sustainability from a source of stress and conflict into a hopeful, shared journey that everyone can take part in, using positive reinforcement rather than guilt.

References

Dowie, M. (2019, October 11). The myth of a wilderness without humans. The MIT Press Reader.

Retrieved September 18, 2024, from https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/

the-myth-of-a-wilderness-without-humans/

Falk, J. (n.d.). Understanding museum visitors motivations and learning [PDF].

https://slks.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/dokumenter/KS/institutioner/museer/

Indsatsomraader/Brugerundersoegelse/Artikler/

John_Falk_Understanding_museum_visitors__motivations_and_learning.pdf

Geib, C. (2022, February 3). How “wilderness” was invented without indigenous

peoples. SAPIENS. https://www.sapiens.org/culture/

pristine-wilderness-conservation/

University of Michigan. (n.d.). Origins of the environmental movement. Give the

Earth a Chance: Environmental Activism in Michigan. Retrieved September 19,

2024, from https://michiganintheworld.history.lsa.umich.edu/

environmentalism/exhibits/show/main_exhibit/origins