“The British Museum fully acknowledges the complex histories of objects within the collection and recognises our responsibility to engage audiences about their interconnected history in the modern world” (Duggal, et al., 2023).

But are acknowledgments of theft in colonization and responsibility in engaging audiences enough?

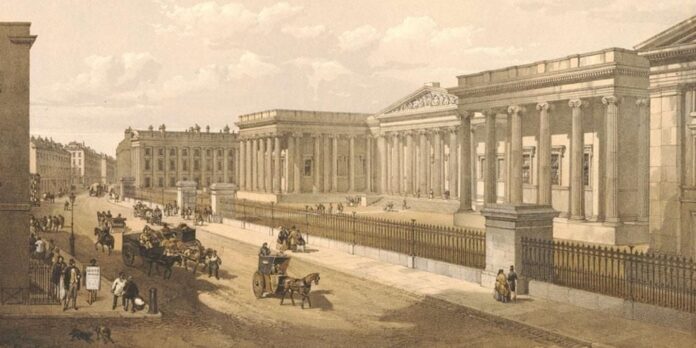

“Founded in 1753, the museum first opened its doors in 1759. Located in central London, the British Museum, one of the city’s most popular tourist attractions with four million visitors in 2022, offers free admission to its permanent collection. The British Museum has long recognised that some of the items it houses are contested – a reminder of Britain’s colonial exploits” (Duggal, et al., 2023).

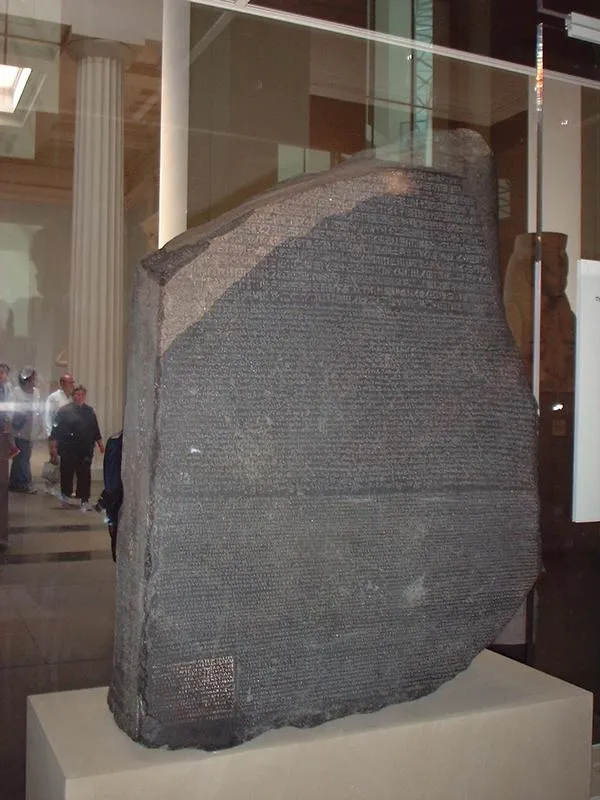

The Rosetta Stone:

“One of the most famous items at the British Museum is the Rosetta Stone. Part of a bigger slab, the stone has carved into it a decree in three different writings – Hieroglyphics (14 lines), Demotic-Egyptian script (32 lines) and Ancient Greek (54 lines). The stone was found accidentally by soldiers in Napoleon’s army, who were campaigning in Egypt from 1798 to 1801. Following Napoleon’s defeat, the stone was shipped to England in 1802. Officials from Egypt have been requesting the stone be given back to its country of origin ever since” (Duggal, et al., 2023).

The Parthenon Sculptures:

“Also known as the Elgin Marbles, the Parthenon Sculptures are part of a frieze from Ancient Greece that adorned the temple of Athena on the Acropolis in Athens. The 17 sculptures and 15 metopes of the original frieze in the British Museum were made between 447 BC and 423 BC. They were removed by Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, when Greece was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. Greece first made a formal request for the permanent return of all of the sculptures in the museum’s collection in 1983” (Duggal, et al., 2023).

“An analysis by Al Jazeera of the British Museum’s online database, as of August 30, found that 2.2 million items from at least 212 different countries around the world had been catalogued. At least 649,727 items were categorised as being made in, acquired or found in the United Kingdom, with most – 625,371 – from England. Outside of the UK, the museum database returned 164,140 results from Iraq, followed by Italy (147,697), Egypt (119,854), France (81,980), Turkey (73,922), Germany (66,273), Greece (64,928), China (58,749) and India (52,518)” (Duggal, et al., 2023).

With only 625,371 out of 2.2 million items being from England, is the British Museum profiting off of historical colonization and theft of cultural artifacts? Is this still colonization? The refusal to give back artifacts stolen during historical colonization and the profiting off of these artifacts in the present day is a statement of colonial power. It is also a refusal to allow cultures to own their history now and in the future. When will reparations take place? And when will these colonized cultures be allowed to thrive in their history again? How can this example of present-day colonization of goods relate to ideas of historical systematic barriers in finance?

References:

Duggal, H., Haddad, M. (2023, August 31). Where do the items in the British Museum come from? Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/8/31/where-do-items-in-the-british-museum-come-from-2