“Decision makers use indicators of progress to assess and design policy,” but what is a good indicator of progress? (Adler, et al., 2016).

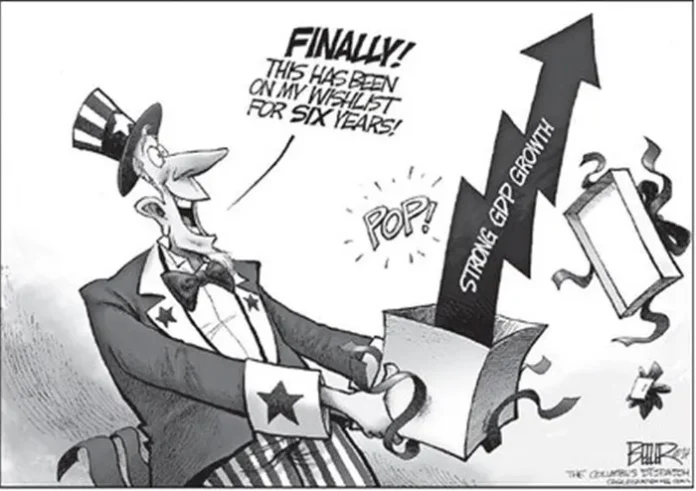

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) “has increasingly become a global proxy for national progress, even though it was never designed as a measure of prosperity; it merely measures the total market value of the goods and services produced by a nation’s economy during a given year (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009). Even its creator, Kuznets, declared that “the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income” (Kuznets, 1934). Regardless, during the past 80 years, institutional architecture and public policy around the world have primarily revolved around maximizing GDP” (Adler, et al., 2016).

So why is it implied that a higher GDP means higher well-being when GDP was never created to measure wellbeing?

“Wealthier people are happier than poorer people,” but is that enough to justify the prioritized pursuit of GDP when “we also know that systematic increases in GDP and globalization without the right policies to protect people have contributed to generating detrimental effects on the quality of social relationships and on individuals’ sense of community belonging” (Adler, et al., 2016).

For example “several public goods and services (e.g., better roads, day centers for the elderly, public squares, and parks) produce costs or benefits that are not easily captured through traditional economic indicators, even though they may significantly improve or diminish citizens’ quality of life” (Adler, et al., 2016).

If policies to protect well-being are not enacted, a country can have a high GDP but still have an unhealthy society. In this context, what is a better way to measure and further improve wellbeing?

Why not use well-being itself?

“Wellbeing data about individuals and nations can provide useful information for policy makers and governments,” but much of this data comes from Subjective Wellbeing (SWB). “Overall, high SWB combines three specific factors: (1) frequent and intense positive affective states, (2) the relative absence of negative emotions, and (3) global life satisfaction” (Adler et al., 2016).

“Subjective questions allow people to express the quality of their own lives, reflecting their own histories, personalities, and preferences. They reflect what people think is important and desirable, rather than what experts or governments think should define a good life” However, “studies on SWB measurement have shown that individuals do not always accurately report their subjective experiences” (Adler, et al., 2016).

Although there could be misinformation in SWB, it is still an important tool, and it can be linked to the measure of well-being in some instances. To combat this “wellbeing scientists are starting to use large social media datasets (“big data”), such as Facebook and Twitter, to track the psychological states of large populations in time and space” (Adler, et al., 2016).

By using well-being as a form of measurement, we can understand how much a community is flourishing which is “the absence of the crippling elements of the human experience – depression, anxiety, anger, fear – and the presence of enabling ones – positive emotions, meaning healthy relationships, environmental mastery, engagement, and self-actualization” (Adler, et al., 2016).

In a real-world example, we can understand that “if wellbeing metrics are used when deciding on the most appropriate tax structures, these indicators may help policy makers design optimal tax structures that maximize tax revenue without reducing societal wellbeing” (Alder, et al., 2016).

This can be applied to personal finance by understanding and measuring how “well” customers feel in their current situation to further design policies and situations that encourage well-being to improve.

References:

Adler, A., Seligman, M. (2016). Using wellbeing for public policy: Theory, measurement, and recommendations. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i1.429