“’You can do anything you put your mind to’” is a message that has been instilled in the minds of North Americans” (Good, et al.).

“People are taught that if they work hard enough, anyone can succeed. This is why many people believe in equality and fairness as forces that shape our economic system and tend to overlook the power of systemic factors like racial discrimination or class barriers in economic inequality. A danger in this type of thinking is that people are tempted to blame individuals for their hardships and for their poverty” (Good, et al.).

But how can we make this abstract concept more real in order to connect with it personally? Is the answer to use games?

“C’est La Vie: The Game of Social Life is a simulation activity – a game – that is designed to help players engage in discussions of structural inequality and self-reflection through first-hand experiences” (Good, et al.).

“To start the game, players are each given a character profile that captures the intersecting sources of privilege and oppression related to race/ethnicity, immigration status, gender, sexual orientation, ability, and socioeconomic status. These factors combine to determine the number of ‘bonus’ credits with which the character starts the game. These bonus credits represent social privileges granted to some groups of people, but not to others. Each player also begins the game with differing degrees of wealth, indicated by starting money credits” (Good, et al.).

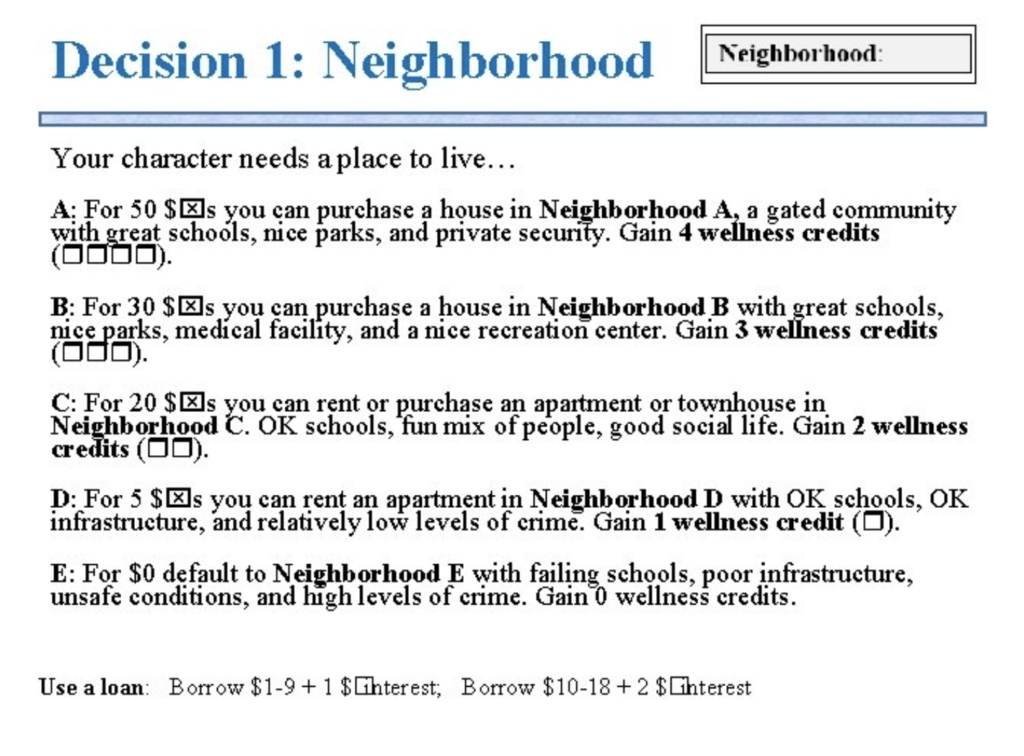

“As the game progresses, players make decisions about housing, education, and occupational attainment. They also encounter a variety of real-life situations, including making friends, getting into trouble, and even dating. Players are instructed to make strategic decisions on behalf of their character that could result in the gain (or loss) of money, bonuses, experience, education, and health and wellness for their character. For example, early in the game players choose housing in different neighbourhoods. The decisions are also impacted by the characters’ membership in privileged or marginalized groups, whether racial/ethnic, gender, sexual orientation, ability/disability, or socioeconomic. The trade-offs in the game, and the players’ interaction with their character’s demographic characteristics, are designed to highlight the complex, and often subtle ways that systems of privilege serve to maintain systems of oppression” (Good, et al.).

“The game also includes several collective decisions (i.e. votes) that are used to further highlight the processes by which systems of privilege contribute to oppression. In one example, players must use their bonus credits to harness the power of the media to lobby for a wellness initiative. Residents of the neighbourhood with the most votes win the wellness credits, while everyone else loses wellness credits” (Good, et al.).

“Because only the most privileged characters have the bonus credits to spare, and players tend to vote based on the self-interests of their own character, the wellness credits almost always go to the most affluent neighbourhood. These decision scenarios highlight how institutionalized privilege serves to help some, while hurting others, even when people are not explicitly motivated by prejudiced attitudes” (Good, et al.).

The game allows people to slightly experience what it is like to be in different priveledged or marginalized groups, but is it really effective in helping people understand the systematic boosts or obstacles that are in our daily lives?

“Assessing the effectiveness of the game is an ongoing process. To date, the game has been assessed in a variety of different environments, including a small university seminar classroom, a large-lecture hall, and as a staff training exercise for a non-profit organization. Using both qualitative and quantitative data, a preliminary analysis demonstrates several important findings: First, the game is engaging, effective and realistic. Players report that they were engaged in role-playing that allowed them to adopt a new perspective and experience the struggle (or perhaps ease) of life in a different social location. Secondly, the game expands players’ conceptualization of privilege and oppression. In particular, the game stimulates self-reflection, such that players reflect on their own lives with regards to their intersecting identities of privilege and oppression. Finally, the game encourages players to focus on structural causes of social inequality” (Good, et al.).

If the game is effective in getting players to think about these concepts in the game in and in reality, would gaming be an effective teaching or reflection tool? Would it be successful at allowing people to think about their personal finance and well-being? What about our collective finances and overall well-being? What ideas could be incorporated into a game that help us break the systematic barriers for some in our financial systems?

References

Good, A., Bramesfeld, K. Fun, games and inequality. Broadbent Institute. https://www.broadbentinstitute.ca/fun_games_and_inequality