“These biological systems are comprised of eight mussels with sensors hot-glued to their shells. They work together with a network of computers and have been given control over the city’s water supply. If the waters are clean, these mussels stay open and happy. But when water quality drops too low, they close off and shut the water supply of millions of people with them.

“The best indicator organisms are those that have specific life requirements, i.e. they have a narrow ecological (occurrence) scale. This means that a number of different factors will limit their vital functions or even eliminate them from the environment.”

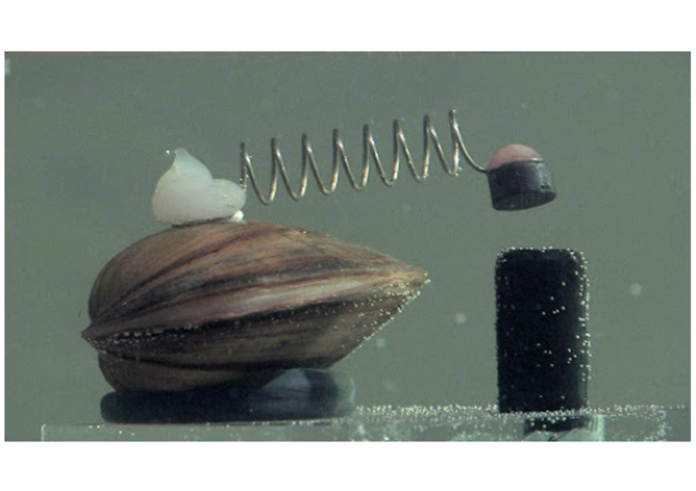

Whenever a mussel clamps down, it closes a circuit via a spring that was simply hot-glued to its shell, which alerts a computer that it may be time to turn off the water supply. The computer’s job is to monitor parameters obtained through artificial sensors and produce an alarm if anything seems amiss. This step is meant to account for any possible change in the individual behavior or mussels, of which there are 8; one presumes they may sometimes grow tired and close off for a nap.

If four of the mussels close at the same time, however, the system shuts down automatically. It’s engineering at its best.

Mussels are typically viewed as a nuisance that clogs and damages water supply systems. But the clam-powered system has been running at the Dębiec Water Treatment Plant since September 1994 and might change that view.

“No computer can replace these super-sensitive mussels.”

Pełka adds that the clams are “paid back after three months of work by releasing them to a place from which they will never be caught again”. While I definitely enjoy the thought of clams earning a comfortable retirement spot, this is done because they eventually become resistant to contamination in the water.” (Micu 2020).

After some follow-up research, I’ve concluded this system could be described as an eco-technology. “An eco-technology is a hybrid system with a non-living part that is designed by humans and a living part (the ecosystem) that self-designs” (Nath 2017). The living, self-designed part of this system is the mussel, and the human-designed part is the computer that interprets the mussels’ actions.

These mussels originally stood out to me because I feel like a lot of environmental solutions are tech and human centered. It’s interesting to see an eco-technology used at such a large scale.

It’s also comical to see people personify the mussels as if they are actually conscious of the scale of their actions, but I think the comedy of the situation points to the fact that we don’t entrust our lives to nature. The natural world is often seen as something to combat because it is characterized as unpredictable and possessed by a logic that is inhuman, and therefore possessing an inferior form of logic/intelligence. In reality, these mussels prove that nature already knows how to regulate and balance itself, and as humans we need to consider ourselves as part of that balance.

Eco-technology reminds me of TEK, or Traditional Environmental Knowledge, which I learned about in my Geology of National Parks course I took last semester. TEK is described as “all types of knowledge about the environment derived from the experience and traditions of a particular group of people” (Usher 2000). Indigenous people would be an example of a group of people that possess TEK.

Although the issue of waste and litter management within my capstone prompt is a human-made issue, what this article shows me is the solution doesn’t necessarily need to be human- centered. In fact, ideally by examining TEK of the past and understanding how environmental knowledge is passed around within local communities today, a proper solution would be a system that includes both human and ecological counterparts.

Micu, A. (2020, December 28). In Poznan, Poland, eight mussels get to decide if people in the city get water or not. ZME Science. https://www.zmescience.com/ecology/poznan-mussel-water-plants-892524/

Nath Bhakta, J., Ghosh, D., & Lahiri, S. (2017). Handbook of Research on Inventive Bioremediation Techniques. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2325-3.ch004

Usher, Peter. (2000). Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Environmental Assessment and Management. Arctic, 53(2), 101-212, https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic849.