Boycotts and buycotts are two common ways that people let their money have a voice. Boycotting is avoiding purchasing things to negatively affect the entity while buycotting is “the act of intentionally buying a product to support a cause” (Bossy, 2014).

These forms of activism “have been used in a variety of contexts such as the American Revolution, Gandhi’s struggle for India’s independence, or the civil rights movement in the United States” (Bossy, 2014).

Personal choices to boycott and buycott have grown into collective movements and two of the social movements that encompass these tactics are political consumption, “a repertoire of action that consumers can use and that involves boycott, buycott, ethical investment, and so on,” and political consumerism, “a critique of consumer society and of traditional consumerism, understood as referring not to the consumption of goods and services per se, but to the endlessly desirous and routinely wasteful consumption of affluent economies” (Bossy, 2014).

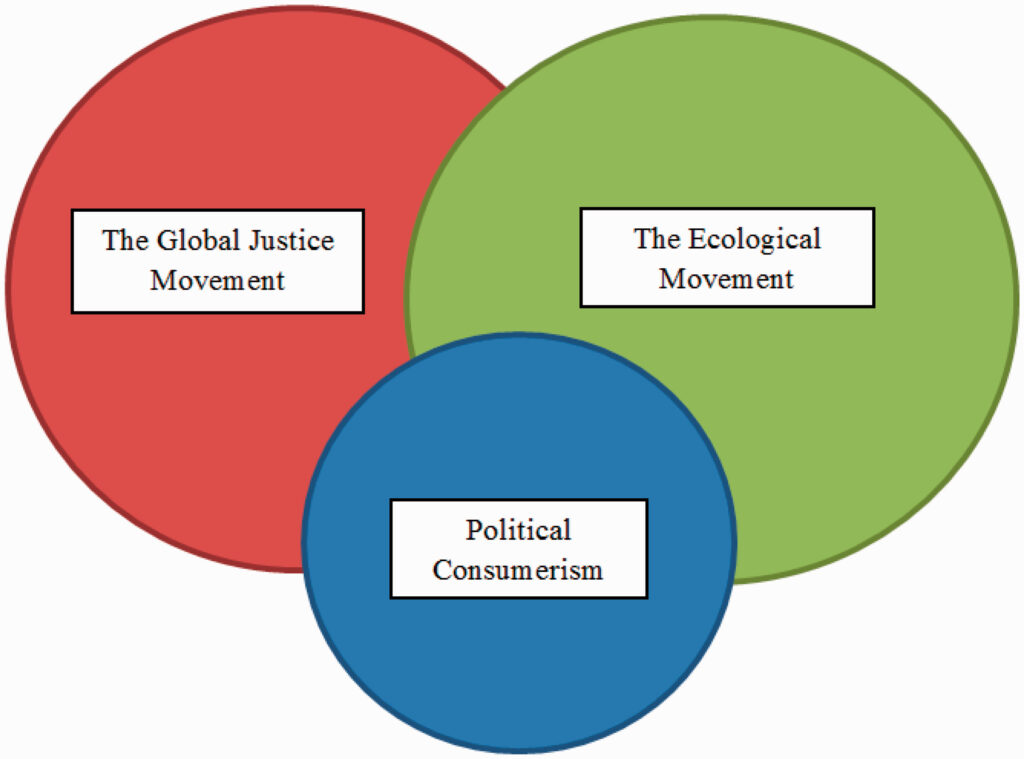

Political consumerism, political consumption, and other social movements are often strongly related and there are places where their struggles are intersectional. This intersectionality allows different groups to work together towards their goals, but it also shows how one movement directly affects another. In a sense, a movement is not complete until the other movements are also complete.

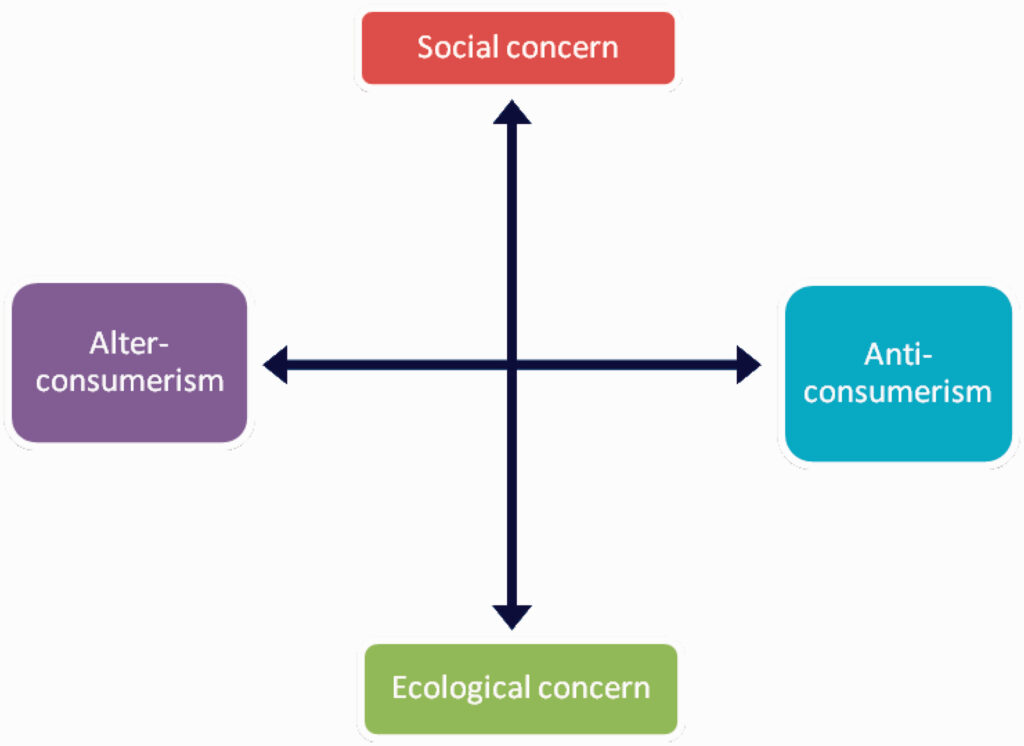

Within the realm of political consumption and consumerism, there are often many different opinions and ideologies. Alter-consumerism is a movement for an alternative form of our current system while anti-consumerism focuses on a radical revolution of how we go about consumerism in our society. There is another factor that plays into how you go about this movement and that is the balance between consumerism concern socially and consumerism concern ecologically. These different ideologies have disagreements but conclude that the current system is not working (Bossy, 2014).

So within a broad movement of different ideologies, one movement is born: one towards a more utopian world of consumerism that fixes all of these categories. A utopia is “a rejection of the existing society” and “the idea that another society is possible and desirable” (Bossy, 2014). This then splits up into utopias for the individual, the community, and the globe which require different strategies to achieve one fully-encompassing utopia.

So how can we use the concept of mapping social movements, strategies, and utopias to help us collectivize our goals for change?

On a personal level, it can be reflecting on your choices and taking action from them. On a community level, it can be finding ways to bond as a community in action. On an institutional level, it can include politics and governmental change. On a global level, it can include spreading awareness and encouraging people to work together towards a common utopia (Bossy, 2014).

In a world where we are consumers of many different things, how can we design to create connections between multiple ideologies and promote collective action toward our well-being?

References:

Bossy, S. (2014). The utopias of political consumerism: The search of alternatives to mass consumption. Journal of Consumer Culture, 14(2), 179-198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540514526238