With the publication of homemaking guides such as 1969’s American Women’s Home, which included a chapter dedicated to the requirements of a proper “Christian Home,” the domestic interior took on a new role as the locus of constructing normative ideas of family, gender, class, race and, of course, sexuality.

The closet was central to this image of heterosexual whiteness. “Holding things at the edge of the room, at once concealing and revealing its interior,” writes Urbach, “the closet becomes a carrier of abjection, a site of interior exclusion for that which has been deemed dirt.” As much as the closet drew speculation about what was inside, it largely functioned to conceal as well as “cleanse” unruly objects and identities that might “soil” the pristine image of heterosexual domesticity. Hence its later connection with the veiling of homosexuality. But the storage closet isn’t the only kind of closet designed to obscure non-normative identities.

As poet and theorist Lucas Cassidy Crawford outlines in Transgender Architectonics: The Shape of Change in Modernist Space (2015), architectural plumbing is a resounding metaphor for our bodily plumbing. If the closet is indivisible from homosexuality, the washroom is inescapably linked to transgender identity. “Plumbing is not a ‘gender-neutral’ term,” says Crawford. “When applied to bodies, the word conceals histories of normative ideas about gender, race, ability and other bodily modes.” Expectations of plumbing run parallel to expectations of bodies, and access to these spaces have likewise been at the core of transgender rights.

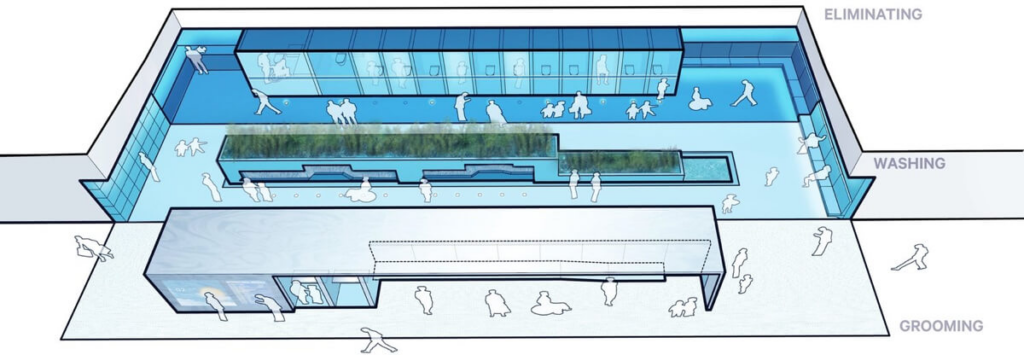

Stalled! (here and next two renderings) is a project by transgender historian Susan Stryker, architect Joel Sanders and professor Terry Kogan.

Conservative legislation, such as North Carolina’s controversial 2016 “Public Facilities Privacy & Security Act,” known as “House Bill 2,” has often looked to limit access to public restrooms by dictating that washroom use must correspond to one’s gender as listed on a birth certificate. Largely touted as safeguards to protect cisgender occupants, the motions have not only demonized transgender individuals but have led to a number of violent attacks, primarily against trans women, in shared public facilities.

“To exhume these ideas and address them, we must redesign actual washrooms and metaphorical “plumbing.’” It’s a challenge that transgender historian Susan Stryker, architect Joel Sanders and professor Terry Kogan have taken up with their ongoing project Stalled!.

When architect Louis Kahn famously quipped, “You say to a brick, ‘What do you want, brick?’ and brick says to you, ‘I like an arch,’” he hadn’t anticipated the material’s response in the hands of activists during the 1969 uprising at New York City’s Stonewall Inn. Though there are countless opinions on who thew the first brick — or if one was even thrown — during the two nights of rioting that followed a particularly brutal and unexpected police raid on the Greenwich Village gay bar, it’s a compelling and enduring myth.

“Stonewall was, at its core, about people reclaiming their narratives from a society that told them they were sick or pitiful or didn’t even exist,” writer Shane O’Neill says. Whether occupying the bar or the streets outside, it was a deliberate act of asserting presence in urban space that had long been used as a vehicle of erasure.

But as much as these places provided room for marginalized communities, they were still fraught with their own anti-Black, anti-trans politics. It wasn’t until well after its establishment, for instance, that the first drag queens, among them transgender activist Marsha P. Johnston, was welcomed to the bar, which had long been frequented by cisgender men exclusively.

In the early 1970s alone, arson attacks at UpStairs Lounge in New Orleans as well as the Aquarius bathhouse in Montreal collectively claimed 35 lives. Many bodies were never identified and were laid to rest in pauper’s graves.

“For the many nightclubs — such as Loft, Danceteria or Mudd Club in New York — designed by unknown architects or short-lived architectural firms, archived information is difficult to find,” explains critic and historian Ivan Lopez Munuera, a contributor to the upcoming exhibition “Night Fever: Designing Club Culture” at V&A Dundee. Though essential in the formation of queer enclaves and their relationship to space, he notes, “their architects, communities, contexts and contributions to the built environment are missing from histories of architecture.”

Wolfgang Tillmans, who has chronicled these performative milieux, from Berlin to New York, since the 1980s. “For me, photographing queer spaces isn’t voyeurism,” he says. “I feel I have a duty to preserve it.” Aiming to ensure the stability of these enclaves in our current climate, Tillmans recently brought together 40 artists to sell posters, thereby keeping a number of nightclubs, venues, bars and other art spaces open as they reel from the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns.

“As an artist and an activist, I’ve learned how important the dance floor is for queer people,” writes Syrus Marcus Ware, co-founder of Toronto Pride’s Blockorama event and a Black Lives Matter member who recently spearheaded a sit-in outside the city’s police headquarters alongside the larger-than-life painting Defund the Police to protest ongoing police brutality. “These spaces are essential,” he notes. “We’ve met our lovers in these spaces. We’ve met activists in these spaces. We’ve become politicized in these spaces.”

In addition to bars and nightclubs, the Black and Latinx members of Harlem’s 1980s ball culture — immortalized in Jennie Livingston’s controversial documentary Paris is Burning (1990) and the subject of FX’s current series Pose — appropriated existing structures like New York’s Rockland Palace to hold their expansive pageants and gatherings. Participants would walk in themed sections ranging from “Butch Queen First Time in Drag” to “Executive Realness,” the winner achieving the goal of being almost indistinguishable from the character being emulated. “You’re not really an executive, but you’re looking like an executive,” says drag queen Dorian Corey in the film. “You’re showing the straight world that ‘I can be an executive if I had the opportunity.’”

In a sense, queer space is also about this realness, which is “not just a sassy by-word for a convincing costume, but a tragicomic disguise of the chasm between what is being emulated and what is absent (namely racial justice, class equality and safety),” according to writer Shon Faye. These spaces, frequented primarily by queer people of colour, were mediums for finding community as well as challenging the status quo that other forms of architecture framed; space-making was integral to their efforts at defying injustice. Instead of simply “passing” as heteronormative, as countless queer bars the world over did, the realness attempted was a more radical aesthetic vision, assuming visual and physical space that had been denied through skillful artifice.

Another blatant architectural reference in Harlem’s ball culture were the “houses” — entire queer families named after opulent fashion dynasties — that defined the scene. Along with their competitive role, the houses served as important places for queer youth to establish systems of support denied to them by their biological families or society at large. In addition to their respective “children,” each house consisted of a “House Mother” or “House Father.” Like the dance floor, the house is central to understanding queer space.

So, too, is accessible housing for queer seniors. As critic Mimi Zeiger points out, queer futurity — the potential for aging — seemed unattainable with the emergence of the HIV/AIDs epidemic. How could one even consider growing old when the lives of friends, colleagues and lovers, such as those chronicled in the Instagram archive The AIDS Memorial, were so tragically cut short? Thanks to more recent advances in advocacy, education and treatment, however, the possibility of a queer future is something real, accessible and now even architectural.

New York-based studio Leong Leong’s recently completed LGBT Center in Los Angeles, which will see youth and senior housing (slated for completion early next year) added to its existing 17,000-square-metre footprint. A similar proposal, in Boston, involves a 74-unit complex designed by DiMella Shaffer. The first of its kind in the city, the structure is described as being “LGBTQ-friendly,” although it’s not exclusively reserved for the queer community.

“The number one issue for LGBT seniors is housing,” Bob Linscott, assistant director of Fenway Heath’s LGBT Aging Project, told The Boston Globe. “There’s a big fear of going to a place where people will be bullied and harassed [in the same way they might have been harassed] decades ago.”

Rather than merely actions or occupancy, queerness might also be regarded as a way to think beyond the very binaries inherent in building. Much of this exploration has — and continues to be — investigated within the context of exhibitions and galleries.

Shortly following the establishment of ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) in March 1987, the New York collective — formed to highlight the severity of the AIDS crisis and the American government’s blatant indifference — was invited to produce an installation for the New Museum’s window overlooking Broadway in Manhattan. The resulting neon emblem, the now-iconic SILENCE = DEATH with its glowing pink triangle, transformed the storefront into a spatial manifestation of absence, one that still feels relevant as reports circulate about the editing of queer narratives from the Canadian Museum of History in Winnipeg.

More recently, the traveling neon-soaked exhibition “Cruising Pavilion: Architecture, Gay Sex and Cruising Culture” examined, as its title suggests, the material structures intertwined with sex — from historic cruising sites to the implication of apps like Grindr. Organized by Pierre-Alexandre Mateos, Rasmus Myrup, Octave Perrault and Charles Teyssou, the show drew vast connections, ranging from DS+R’s Blur Building (considering it akin to the atmosphere of a steam room, a cloaked public space that “makes private action possible,” according to Renfro) to works by Studio Odile Decq and Andreas Angelidakis. In these conceptions, queer space or queer architecture is not simply a place used or appropriated by non-heterosexual people, but a performative strategy to challenge the behaviours, rules, expectations and situations framed by the built environment. “[Queerness] is an open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances, resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning,”

In the end, locating a permanent, stable and material queer space may not be possible. But that’s the point. It’s in the revisiting of these pasts and presents, through a variety of strategies, that allow a glimpse at the potential of queer futures — even if, as noted throughout, they are only a small fraction of the many ways queer individuals and communities navigate space.

“There is no queer space,” the historian George Chauncey aptly concludes. “There are only spaces put to queer uses.” And as we begin to slowly enter the world after sheltering in place, witnessing ongoing anti-Black and anti-trans violence, it has never been more important to remind ourselves exactly whose uses these spaces are being put to.

Analysis

These examples show the importance of dance, drag, architecture, when it comes to building a physical queer safe space. We must rewrite assumptions in architecture to exclude functions of architecture that only serve cishet people. Erasing the function of gender within bathrooms is highlighted in this article and provides a perfectly fine bathroom that isn’t for a particular gender. Many Gay bars are experiencing straight women due to them feeling safer around gay men, then follows the straight men who hunt them like prey. I wonder about what the queer community needs to add resources back into these queer spaces. Drag is definitely something to look into as they draw in queer crowds and have a platform to speak to an audience (both digital and physical).