Introduction

Financial Literacy has been a crucial topic affecting many individuals around the globe. Numerous businesses that have recognized this issue have since opened up new services to help individuals navigate their responsibilities as consumers and spenders and sparked a new trend all around different social media platforms. In schools, money has been subtly implemented in general education such as language arts or mathematics courses; however, recently, different locations have opened up classes focusing solely on financial literacy through business, economics, and entrepreneurship. However, these solutions have been promoted in a rather scattered manner without much of a systematic flow backing the topic up causing inefficient learning strategies.

Huntington Bank reached out to OSU’s Industrial Design program to be a sponsor for a thesis project to help provide an innovative solution that could encourage and foster such topics for individuals of different demographic regardless of where they may land in the financial literacy journey.

Exactly what age group would it make the most sense to design for than middle school children that have just received recognition as economic citizens? By the time children reach the ages of 10-12, many have attained the resources to mobile connect with friends from a distance or visit public facilities with them which requires some extra bit of funding[1]. By the time students reach high school, many courses have already implemented finance-focused courses, which still although does not ensure the student’s ability to fully become financially literate, is arguably too late and too close to their financial independence as a soon-to-be college student. Even in a review of financial literacy programs for different grade levels, results have shown there already being a gap between groups, predominantly male, who are overly confident in the subject, and groups, predominantly female, who lack confidence starting in secondary school regardless of the two groups receiving similar financial education [2].

Research

Included in this research dossier is a set of primary research working with middle school guardians and students alongside secondary research looking at previous research conducted on financial literacy from a generalized scope and lenses of science & technology, business, and arts.

The primary research is divided into four parts inquiring about middle school students through Linkedin, Facebook, and Reddit, and in-person co-design research with middle school children with, of course, the applicable permission from their parents. Primary research activities specifically included:

- A survey directed toward middle school guardians to gauge the importance of financial literacy in their children’s curricula

- Conversational-based Interviews with both middle school guardians and students to discuss tools and discussions occurring in the family to promote financial literacy and incentivize responsible spending habits

- A Hypothetical Allowance Activity for participants to imagine a hypothetical shopping spree and elaborate on how from $5 up to $1000 would be used

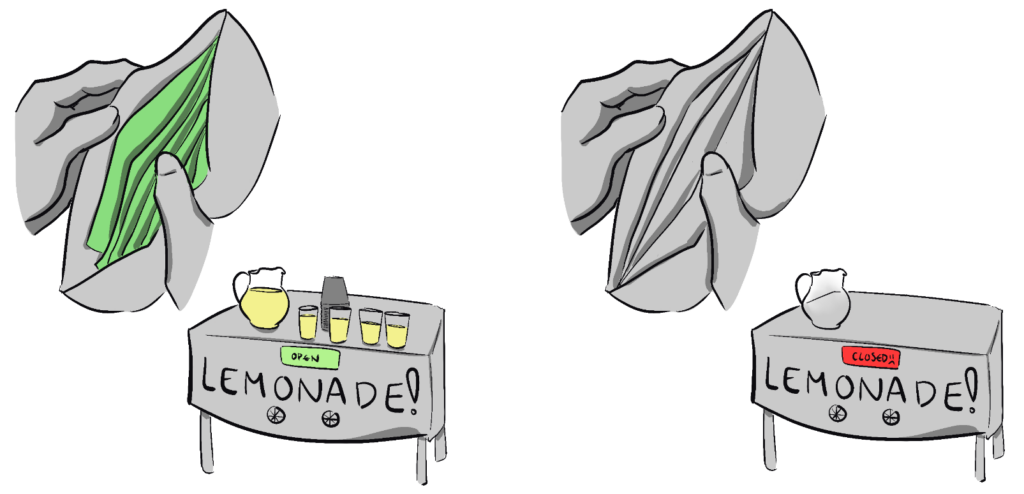

- A Hypothetical Lemonade Stand Activity to analyze how participants would distribute a $100 bill to structure their very own lemonade business

The survey inquiring middle school guardians to address their opinion on the importance of financial literacy in their children’s curriculum was sent through numerous Reddit and Facebook communities that were packed with middle school moms, dads, and teachers in addition to more general groups that don’t necessarily fit the demographic but still had relevant information. In total, only 21 responses were attained heavily weighing on female respondents; however, relatively evenly divided among the grade levels and age groups.

On a positive note, 71% of respondents found financial literacy to be a necessary topic in school; however, unfortunately, the majority of the respondents although not satisfied with their own financial literacy, did feel comfortable taking the responsibility of educating their child on this topic in their own hands. How can this make any sense–why would anyone who wouldn’t feel confident in their own knowledge and skill want to potentially run the risk of providing false information on a topic they deem essential in their school’s curriculum? The answer to this question may be rooted in the generational issue of financial literacy not being implemented in the country’s required learning standards. This topic was only a necessary subject in Ohio’s Learning Standard [3], potentially leading to parents who were not given the opportunity as a child to have no choice but to rely on their own past experiences to stop their children from taking the same path.

According to the results of another question, 71% of participants also deem budgeting to be the most important topic while entrepreneurship and investing were deemed to be equally least important to be taught in school. The amount of popularity of budgeting was no surprise and lined up with the weight placed on Ohio’s Learning Standards for Financial Literacy as well as the thorough responses to rules they set to incentivize their children into responsibly using their money; however, entrepreneurship and investing coming as the lowest two subjects were not expected as they did not align with the business side of this research dossier. Countless young entrepreneurs have found immense success in starting their own businesses by investing. Additionally, other resources have highlighted the importance of entrepreneurship leading to schools offering courses dedicated to the topic.

The interviews were conducted with a series of middle school children ranging from the ages of 11 to 14 with a couple being with parents. Two participants mentioned having siblings, both receiving similar financial privileges at the same time due to only being a couple of year apart.

Some of them at this point had the freedom to receive allowances and spend them on almost anything they would like while others although didn’t receive allowances, did have their parents pay for things if needed for school. Astonishingly, even with the freedom to spend their money freely, none of them had reckless spending habits and understood where each dollar had went to.

One participant (female, 14) that works at her family’s restaurant even went out to say that her parents trust her to not spend it on useless objects and will not even keep track of her spending. “The building up of money [she] sees gives [her] satisfaction and makes [her] feel rich!” she states as she describes the mountain of loose $20 bills on her night stand. However, needless to say, the loose cash out in the open in her room proves the lack of security in her financial habits regardless of the right attitude in saving that money. Even though she knows having Greenlight [4] as an option to keep that money stored in a debit card, she claims to push that back due to her already having an account connected with her parent’s account. This solution has, however, caused difficulties in separating her money from her father’s account, which has caused other complications.

Another participant who has three children has also stated not having any problems with their middle school child’s (male, 13) spending, but rather her college aged child’s (male, 21). As a middle schooler, she mentions, there is nothing for her son to really spend on except some snacks and occasionally Nintendo Switch games, while her college son needs a lot of money to eat out and go out with his friends. Additionally, because her middle school child’s income was not as high as a college student, she did not have to worry about him making reckless purchases as she understood he never has the extra money to spare him from doing so.

Lastly, I also had the chance to speak with a Muslim participant that has a rather structured set of rules for his family’s finances. The two youngest boys who are currently in middle school (11 male, 13 male) have their own debit cards that are tracked by himself. Their school materials, as explained above, are purchased directly by him and they also each receive some additional allowances. Because their studies take priority over anything, their allowances are not made over completed tasks, but rather a set amount for each month.

The hypothetical allowance activity was also conducted with similar participants who had enough time to stick around to participate and a couple of new participants as well. On a Miro board, they were given four quadrants, each representing the amount of money they would receive for a scenario. Starting from $5, they would need to figure out what they would exactly use their money for. They would need to do research to find the exact prices of each product to not go over their budget. Although they may start off with small mundane products, for their last scenario ending with $1000, they would need to make more bold decisions. Of course, they would also have the option to save their money, but they would need to mention where that money would eventually be saved toward. They were also encouraged to keep in mind whether their purchase is cost efficient–if the amount spent for the particular product balances out with the value or time spent with it after being purchased.

In contrast with the interview, more drastic differences between spending habits were apparent through this activity. Some individuals who had close daily contacts with their parents (one previously mentioned individual who works for her parents restaurant and another with a stay-at-home-mother) were often seen saving most of their money in all scenarios, while others who claimed to often stay at home indulging in their personal hobbies alone tend to use most, if not all, of their money to expand their flexibility in such indulgement such as purchasing a new console for if their hobby was to game.

Another pattern could be seen comparing how most participants in scenarios <$10 spent their money on either on products that lasted short term or mystery prize products that would be at low risk even if they were to not win. On the other hand, when they were told to have more freedom spending $100-1000, they were seen making bolder decisions on purchasing products that they only dreamed of that their parents wouldn’t allow them to buy. These bolder purchases for the first set of participants were taking a day trip to an amusement park with their friends or upgrading their airpods while the second group was seen purchasing new mobile devices or rare LEGO sets. One participant listed one product for each of the expensive two scenarios that amounted to almost perfectly $100 and $1000.

The hypothetical lemonade stand involved the same group as the previous activity to map out a business plan for their very own lemonade stand starting with $100. Generally, all participants began listing out what ingredients they would need to set up their stand. Most used google shopping as a reference to how much they might spend on each item. Astonishingly, only one participant searched for a precise recipe for how much of each ingredient would be needed to make her batch of lemonade. The rest seemed to have a hunch on how much was needed but did not bother to do in-depth research.

Across all participants, it was even clear that none of them truly looked into the quality of the flavor of their lemonade. The majority had never even made lemonade in the past, but were confident enough that their businesses would make a profit regardless as long as marketing was prioritized and they had the three main ingredients to make lemonade. One exception was when a participant successfully managed to come up with a free and effective modern method of advertising her business: that being the use of Instagram. This way, she was able to focus all of her $100 on the ingredients for the lemonade. Regardless, this participant also failed to ensure her lemonade would taste good.

A strong connection between the results of the two activities could be seen with their spending habits reflecting on their business decisions. One participant that owned the restaurant was seen wringing out every penny she could from her parent’s business such as transportation costs, pitcher costs, and the location she would set her stand up in. She understands that since most of the customers order sweet drinks rather than water anyway, her drinks would successfully sell and selling sour lemonade would make customers hungry leading to even more business for her family–a win-win situation. The other participant that was seen saving most of her money also saved the majority of the $100 for if her first day in business was not as successful. The two participants had both spent around double the time of the other participants to look for the most cost-effective ingredients for their stand to save the most money and ensure a successful outcome. However, the other group seen to maximize their spending in the first activity both used up the majority of their $100 making general assumption as to how much each ingredient would be worth how much without extensive research.

Conclusion

Overall, this study has made it clear that middle schoolers are not given the adequate educational attention they need to become financially prepared as an economic citizen. Very few tools outside of the classroom are designed to cater to the developmental stages of a middle schooler. Although they do have their parents to rely on, that is not always equivalent to a flushed-out course in school. Depending on the rules these parents have set for their children, some may not even have enough opportunities to experiment with money which could lead to reckless spending habits in the future (similar to those seen in the co-design activities). Through this project, I would like to develop a solution that can expand their resources outside of the classroom to fill in any gaping knowledge, skill, or behavior needed to attain financial literacy.

[1] Child development: Milestones, ages and stages. Children’s Health Orange County. (2021, December 7). Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://www.choc.org/primary-care/ages-stages/

[2] Amagir, A., Groot, W., Maassen van den Brink, H., & Wilschut, A. (2018). A review of financial-literacy education programs for children and adolescents. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 17(1), 56–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047173417719555

[3] Ohio’s learning standards for Financial Literacy. (n.d.). Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/Financial-Literacy/Financial-Literacy-Standards/FLFinalStandards060518.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US

[4] Lake, R. (2022, July 6). Greenlight Card Review. Forbes. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/advisor/banking/greenlight-card-review/