On the list of materials people use most, concrete may be a runner-up, but it isn’t small potatoes. Second only to water in terms of how much is used across the globe, the ubiquitous construction material is produced in staggering quantities. According to industry analysts, some 30 billion metric tons of concrete is used globally each year to build bridges, roads, highways, high-rise buildings, sewage systems, and more.

Without a doubt, the hard-as-rock material supports much of the modern world. It’s also responsible for a lot of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. The high-temperature process for manufacturing cement, the all-important glue that binds the components of concrete, accounts for roughly 8% of the world’s anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions and consumes 2–3% of the global energy supply, according to the International Energy Agency.

A different way to tackle concrete’s CO2 problem is to reformulate cement with similar-behaving materials that inherently generate less CO2 than the ones used in traditional manufacturing methods. Another option is finding materials that enable manufacturers to use less of the CO2-generating components.

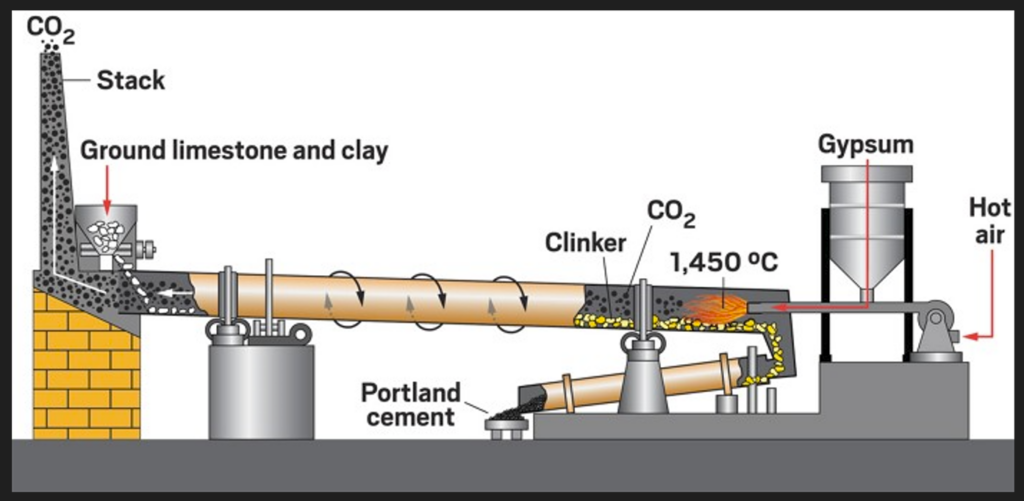

The standard material made by today’s cement companies is known as portland cement. The procedure for making it was developed in England about 200 years ago and has not changed much since then. The name comes from the resemblance of the hardened material to stone quarried on the Isle of Portland in England.

The method calls for heating powdered limestone, a widely available, inexpensive material, and clay to roughly 1,450 °C in a kiln. The high-temperature process, known as calcination, converts calcium carbonate (CaCO3), the principal component of limestone, to calcium oxide (CaO), or lime, releasing CO2.

That simple reaction, which is key to making cement, is the source of about half the CO2 emissions in cement manufacturing and a major reason why reducing emissions is challenging, says the Ohio State University’s Lisa E. Burris, a cement specialist and civil engineer. The bulk of the other half of the emissions comes from burning fossil fuels—often coal—to heat the kiln.

Analysis

This article was really helpful to me in understanding all the different sides of concrete. From its creation, to its properties, to the waste it produces. It also was helpful in understanding more eco-friendly alternatives to typical modern concrete. I had no idea concrete produced that much CO2. With an understanding in the background of concrete, I will be able to more acutely utilize the material in my thesis project. I would like to explore and stretch the boundaries of concrete’s uses and see just how far I can push its applications.

Take-Aways

Concrete produces a significant amount of CO2 – Alternative materials in its “mix” could reduce the environmental impact