By:Sara Gerke, Carmel Shachar, Peter R. Chai & I. Glenn Cohen

Published in Nature Medicine Journal

Published: 07 August 2020

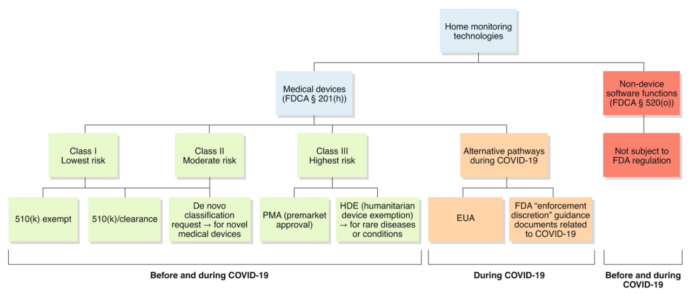

Classification of home monitoring technologies

Some home monitoring technologies are classified as “medical devices” under Section (§) 201(h) of the US Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) since they are “intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions, or in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease,” do “not achieve its primary intended purposes through chemical action within or on the body of man” and are “not dependent upon being metabolized for the achievement of its primary intended purposes.” Medical devices are classified into three classes (i.e., I, II, or III) on the basis of their risk (from low to high). The FDA usually reviews medical devices through different premarket pathways, depending on their risk classification (Fig. 1). Notably, software functions may also fulfill the device definition. The FDA refers to these as either ‘Software in a Medical Device’ or ‘Software as a Medical Device’6. While the former is software that is an integral part of a hardware medical device, the latter is standalone software that as such is a medical device and is intended to be used for medical purposes7,8. For example, Apple launched an upgrade in 2018 to turn its watch into a personal electrocardiogram (ECG), which has enabled consumers to monitor their heart rhythm9. The FDA considered this app to be a moderate-risk device that requires special controls to provide reasonable assurance of its safety and effectiveness and thus classified this ‘ Software as a Medical Device’ a class II device10.

However, some home monitoring technologies are not considered medical devices and thus are not subject to FDA regulation. In particular, FDCA § 520(o), introduced by the 21st Century Cures Act, contains an exception from the device definition for certain software functions (Fig. 1). Examples would include an app that monitors users’ food consumption to manage nutritional activity for weight management, or an app that exclusively monitors users’ daily energy consumption and exercise activity to maintain and improve their good cardiovascular health11.

The appropriate regulatory pathway is especially important during a pandemic, since there is pressure to speed up innovation but to not increase risk. The FDA has recently clarified that it does not consider most software systems and apps for public health surveillance to be medical devices12. In particular, the FDA noted that products that are intended to track contacts or locations associated with public health surveillance are usually not subject to FDA regulation since they generally do not fulfill the medical-device definition12. Consequently, the determination of whether the software function is considered a medical device is always made on a case-by-case basis.

Emergency Use Authorizations for medical devices

The US Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) determined on 4 February 2020 that there is a public-health emergency on the basis of the spread of SARS-CoV-213. On the basis of this determination and to address the COVID-19 pandemic, the HHS secretary has issued three Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) Declarations related to medical devices. The first is for in vitro diagnostics for the diagnosis and/or detection of SARS-CoV-213, the second is for personal respiratory protective devices14, and the most recent one broadly applies to medical devices, including alternative products that are used as medical devices, such as home monitoring devices15.

So far, the FDA has already issued several EUAs for home monitoring devices (‘EUA home monitoring devices’) to address COVID-1915,16 (Fig. 1 and Box 1). For example, an EUA was issued to G Medical Innovations for its VSMS patch intended to be used by healthcare professionals for remote patient monitoring of the QT interval of an ECG17. It is intended for use on patients over the age of 18 with COVID-19 who have been treated in hospitals with drugs that can cause life-threatening arrhythmias17. The patch, worn on the patient’s upper left chest for up to 14 days, is linked to a smartphone, which then transmits the data to a call center, run by G Medical Innovations, for QT analysis. The clinical findings are compiled by a certified cardiographic technician and are subsequently sent to the doctor at the hospital17. It is also easily conceivable that similar devices could be deployed further. Indeed, in 2017, the VSMS patch received the CE mark — a precondition for bringing a device to market — in Europe for home use in patients17.

It is likely that the FDA will issue more device-related EUAs in the coming weeks, including home monitoring technologies. However, authorization of home monitoring devices via the EUA pathway does give rise to potential risks. First, these are uncleared or unapproved medical devices or are cleared or approved devices for an uncleared or unapproved use. The FDA assesses these devices on the basis of four criteria only (FDCA § 564(c)) (Box 1). In particular, one of the criteria is that there is a reasonable belief that the device may be effective in treating, diagnosing, or preventing COVID-19. Thus, the issuing of an EUA does not suggest that the product is safe or effective for monitoring17. Furthermore, another criterion for authorization is the performance of a risk/benefit analysis, and it is difficult to determine where to draw the cut-off for authorization on the basis of this type of analysis. Regulators should always make such decisions carefully and thoroughly, even in times of crisis. Second, when issuing an EUA, the FDA can waive certain requirements that usually help to reduce risks. For example, for the VSMS patch, the FDA waived the requirements for good manufacturing practice, which would be otherwise applicable17. However, such requirements have been developed to prevent harm to the end user and to minimize the risks involved in the manufacture of devices. It would thus be desirable that makers of EUA home monitoring devices build into their manufacturing process as many safeguards as possible to ensure that their products are safe as well as effective in fighting COVID-19.

There are also more-specific risks relating to EUAs for home monitoring devices. In particular, home monitoring technologies include a certain amount of false-positive and false-negative results, such as those caused by incorrect measurements or a failure to measure18. For example, a delay in treatment due to a failure of the device to detect a life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia may have disastrous consequences for a patient’s health. This also raises questions of liability. When the particular circumstances and facts are taken into consideration, the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act may provide liability immunity to a manufacturer of an EUA medical device19,20. But it is also crucial for manufacturers to understand that the FDA’s nonbinding guidance documents for industry and FDA staff about enforcement discretion for certain medical devices related to COVID-19 (Box 2) do not bring such devices within the scope of the PREP Act21 and thus do not provide immunity from liability.

Further risks of home monitoring technologies may include people’s over-reliance on their output without seeking medical advice or the mishandling of such products by recipients — who have a greater range of mental and physical abilities and medical competency than clinicians do — in the absence of direct supervision by healthcare professionals10,18. In the case of Apple’s ECG app, to mitigate the identified risks, the FDA explicitly required, among other things, rigorous clinical-performance and human-factors testing — a demonstration that the user can use the medical device correctly by only reading the labeling and can correctly interpret its output and comprehend when to seek medical help10. In contrast, the FDA has issued EUAs for home monitoring devices on the basis of, among other things, “reported clinical experience”17,22,23. We understand that new digital health solutions need to be deployed quickly to address the COVID-19 pandemic, in particular by reducing contacts between people. Nevertheless, to mitigate risks, companies should make sure, to the best of their ability, to test their products as rigorously as possible, such as by carrying out clinical- and non–clinical-performance testing and human-factors testing to demonstrate safe and effective product use by users in the USA24. This approach is also beneficial for companies in the long term, since an EUA is usually effective only until it is revoked or the applicable HHS secretary’s EUA COVID-19 declaration is terminated (FDCA § 564(f)). Moreover, communication is key for avoiding over-reliance on EUA home monitoring devices, as well as their mishandling (Box 3).

FDA-unregulated software functions

Home monitoring technologies raise, in particular, safety issues, since some of them are not considered medical devices under FDCA § 201(h) and thus do not need to undergo any review by the FDA (Fig. 1). For example, if a COVID-19-exposure-notification app fails to notify a user of their potential exposure to COVID-19, this could result in the user’s spreading the virus.

The risks noted above can be alleviated if device developers take an ethical approach. Ethics requires more than providing reasonable assurance that the product is safe and effective. In fact, technology companies should follow not only the principle of non-maleficence (‘do no harm’) but also principles of autonomy, beneficence, and justice25. Home health technologies need to be designed in a way that maximizes people’s autonomy to the greatest extent possible while at the same time benefiting society and helping to tackle the current public-health emergency26. When developing these products, makers should, for example, ensure they mitigate biases and train their algorithms on unbiased data. They preferably should also work in interdisciplinary teams to reduce the risk of incorporating unconscious bias into the code. It is also essential that during the process of designing home monitoring technologies, technology companies adopt a system view rather than a product view27. A system view requires that companies, among other things, look at the context in which the home monitoring technology will be deployed (e.g., the home setting) and analyze the additional challenges that need to be overcome for successful implementation. For example, developers should consider the practical implementation aspects of home monitoring technologies, such as the need for users to have a wireless internet infrastructure. A system view also requires that developers think about and address the interaction between the user and the product, the design interface, the accessibility of their products for all populations (so that they are immune to language barriers or to inaccessibility to those with disabilities), and issues of reimbursement and just allocation. For example, developers should consider the racial disparities that surround access to these technologies among vulnerable populations who may be most in need of these products. The FDA also developed non-binding guidance on “Design Considerations for Devices Intended for Home Use” that assists them in developing and designing home-use devices with appropriate standards of safety and effectiveness28. The European Commission’s High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence also has Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence29.

More work still needs to be done for better understanding and articulation of how to achieve the goal of designing ‘trustworthy’ digital health solutions such as home monitoring technologies. It will be vital to develop ethical guidelines tailored explicitly to home monitoring technologies by involving all stakeholders in the field — in particular, the users of such products. Health psychology may also serve as a useful tool for guiding the design of home monitoring technologies26. During this pandemic, speeding up of the development of home monitoring products has been indispensable, but developers should not forget to continue to practice ‘ethics by design’ without making too many trade-offs30, to continuously monitor these products31 and adjust them where necessary, to learn from mistakes, and to improve and develop a ‘gold standard’ after the pandemic. Technology companies should also be aware that tort claims by users that home monitoring products that are not classified as medical devices are defective will probably be governed under product liability law and that there is no immunity under the PREP Act.

Fraudulent home monitoring products

Unfortunately, some companies’ goal is to make a profit during this public-health emergency with indifference to patient and/or user welfare. The FDA has already warned consumers against fake medical products that claim to treat, prevent, or cure COVID-19, such as unauthorized vaccines or home test kits32. The US Federal Trade Commission is also warning consumers to avoid coronavirus scams, including ignoring online offers for home test kits and vaccinations33.

It is essential that consumers be adequately protected from fraudulent home monitoring products. State attorneys general should monitor this area closely and bring consumer-protection-act claims when appropriate. Clinicians can also help to educate patients and warn them about particular fraudulent products in the field.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-0994-1

Summary: This article brings an important set of design criteria having to do with safety. The monitoring of children on respirators is a serious topic that will require extensive testing and certification before any product could be trusted to keep a person alive. The article also brings up the point that designers should not only “not harm” but also honor “principles of autonomy, beneficence, and justice.” This means looking into social and ethical needs surrounding my topic.