Author: Christina Öberg, Tawfiq Shams, Nader Asnafi

Publisher: TIM Review

Date: June 2018

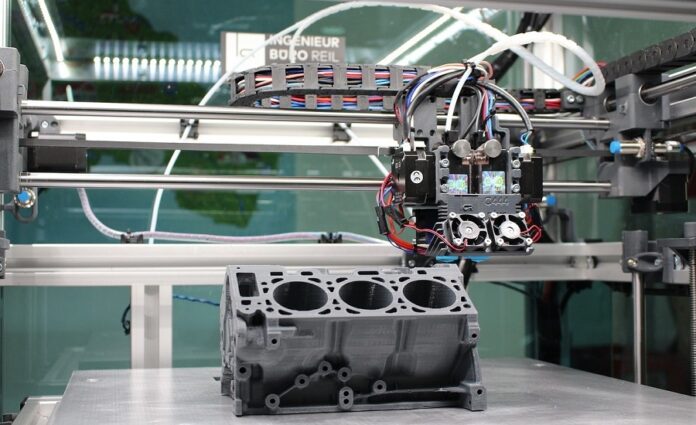

In the article by Öberg, Shams, and Asnafi they discuss how additive manufacturing is expected to change the ways in which business is run. In the case of additive manufacturing, new technologies may constitute challenges as well as opportunities for companies linked to rapid prototyping, rapid tooling, direct manufacturing, and home fabrication.

Introduction

In recent years, interest has risen in additive manufacturing, that is, layer-based 3D printing of goods (Conner et al., 2014; Go & Hart, 2016). Although concerns are still placed on the challenges of getting the technology to work (Gardan, 2016), several industry actors have started to explore the business potential of additive manufacturing. Research largely remains focused on technological advancement, although voices have recently been raised about how additive manufacturing research needs to be integrated with industry (Simpson et al., 2017), and thereby affecting business practices. In short, additive manufacturing is expected to change the ways in which business is run (Brennan et al., 2015; MacCarthy et al., 2016).

This article focuses on the meaning of additive manufacturing for individuals firms by adopting a business model perspective (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010; Zott et al., 2011) on additive manufacturing. Business models refer to conceptual descriptions of a company and its business logic (Osterwalder et al., 2005; Zott et al., 2011), that is, how the company is organized and earns its income. Business modelling describes change processes related to how business is pursued (Zott & Amit, 2010). For additive manufacturing, such changes would follow from the prospective for local manufacturing (e.g., Rogers et al., 2016), but also from completely new designs and materials (Sharma et al., 2017), and companies may try to reposition themselves along the supply chain as their current positions are challenged by local manufacturing and home-based production, for instance (Shams & Öberg, 2017), in turn affecting the business models.

This article addresses whether companies’ business models and changes to them are considered in the present literature on additive manufacturing, and how changes to individual companies’ operations can be understood from present research. The article presents a literature review on additive manufacturing with the underlying question of whether and how the research indicates new business models of companies, the transformation of current business models, or the development of completely new ones. The purpose of the article is to summarize current knowledge on additive manufacturing within management and business research, and to discuss future research directions in relation to business models for additive manufacturing.

The article contributes to previous research by examining how the emergence of additive manufacturing affects existing business models. It further points out research gaps in the intersection of additive manufacturing and business models. The contributions are important due to the emerging practical interest in additive manufacturing (Simpson et al., 2017) and because the literature specifically focusing on business models and their changes related to additive manufacturing has not previously been systematically summarized and analyzed.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. After this introduction, the theoretical building block of business models is presented, followed by the research design. Findings from the literature review are described and analyzed by looking into business model traces in the literature. The article ends with conclusions and a description of a future research agenda on additive manufacturing linked to business models.

Business Models

Business models describe a company’s business logic: what it does, how it is organized, how it earns its income, and how it reaches those resources needed (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). They thereby adopt a holistic perspective on the company’s business (Bolton & Hannon, 2016) and link various activities together (Zott & Amit, 2010) at the centre of what is offered to customers (Margretta, 2002; Teece, 2010). In the general description of business models, one key aspect is the border between activities of the company and those of external parties. Research has here referred to how business models may be open or include border-spanning activities (Vanhaverbeke & Chesbrough, 2014), thus emphasizing the business model’s connection to supply-chain decisions (Lambert et al., 1998; Nordin et al., 2010) in how the business model includes make-or-buy decisions related to core and strategic competences of the firm.

The literature provides several ways to describe business models, often reflected as canvas and non-canvas models. The canvas models refer to illustrative descriptions of a company’s different processes (such as resource provision, value creation, and customer offering, as in Osterwalder et al., 2005), whereas the non-canvas models refer to textual descriptions of, for instance, activities (such as the description of content, structure, and governance of activities, as in Zott & Amit, 2010). The business model canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) describes key resources, activities, and partners on the providing side; the value proposition (the offering); customer relationships, segments, and channels on the sales side; along with revenue streams and cost structures. Key resources, activities, and partners describe what is needed to produce the company’s services or products, and what part of these are made by the company or other companies. The value proposition reflects how the company puts forth its products or services to customers that are then to decide their value. It includes the product, price, extended product, etc., and is what creates the competitive edge of the company’s offering. How the customers are reached is understood through descriptions of channels (such as through independent retailers, the Internet, etc.), whereas segments describe what portion of the market the company aims to reach. Customer relationships, lastly, reflect the relational or transactional characteristic of exchanges along with how resale is created. Cost structures define the types of costs (fixed, variable, etc.) that the company’s operations create, whereas revenue streams reflect structures of payments and financial deals with customers.

Business modeling puts focus on the development of new business models or changes to current ones, resulting from opportunities in the market as well as challenges manifested in awareness of contextual change (Johnson et al., 2008). In the case of additive manufacturing, new technologies may constitute challenges as well as opportunities for companies linked to rapid prototyping, rapid tooling, direct manufacturing, and home fabrication (Rayna & Striukova, 2016), for instance, which would affect and require changes to the company’s business model.

As a means to analyze previous additive manufacturing literature in the business and management research, this article juxtaposes the ideas of Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) with those of Zott and Amit (2010), so as to capture business models (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) and changes to them (Zott & Amit, 2010). Figure 1 outlines this framework. Osterwalder and Pigneur’s (2010) framework consists of the following: key resources, key partners, key activities, the value proposition, customer relationships, customer segments, channels, revenue streams, and cost structures. Zott and Amit’s (2010) description of content, structure, and governance refers to what activities are pursued (content), how they are linked (structure), and who performs the activities (governance), so as to capture their changes.

Figure 1. Analytical framework

Research Design

The article is based on a systematic literature review (cf. Tranfield et al., 2003) conducted as two separate searches so as to capture business models and business model changes in the additive manufacturing and 3D printing literature. The first search provided a very limited number of articles, therefore a second search focused more broadly on additive manufacturing and 3D printing in the business, management, and operational management literature to see whether any traces of business model parts (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) were described in that literature. Both searches used the academic database Web of Science. The literature reviews were delimited to journal articles (thus excluding conference proceedings, etc.). The reason for using the search terms “additive manufacturing” and “3D printing”, respectively, was how an initial search only including additive manufacturing failed to capture some of the predefined relevant articles connecting related methods to business models.

The first search, which focused on “additive manufacturing” or “3D printing” in combinations with “business model” or “business logic” resulted in a total of seven journal articles for the years 2014–2017 (starting date set by occurrence in the database, end date defined to capture entire years):

- Bogers, Hadar, and Bilberg (2016)

- Flammini, Arcese, Lucchetti, and Mortara (2017)

- Holzmann, Breitenecker, Soomro, and Schwarz (2017)

- Kurman (2014)

- Laplume, Anzalone, and Pearce (2016a)

- Pisano, Pironti, and Rieple (2015)

- Rayna and Striukova (2016)

Among these articles, the one by Flammini and co-authors (2017) does not describe additive manufacturing beyond exemplifying it as one of several technologies, leaving only six articles for further inclusion.

Based on the limited number of articles resulting from the initial search, the second search was conducted, this time focusing on the description of any of the parts of the business model canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) or changes thereto as means to code articles in the business and management area. Rather than searching for each of these terms and variations thereof, this second search focused on business research on additive manufacturing and 3D printing and then analyzed the articles through the business model canvas. The search focused on the following research areas: operations research management science, management, and business (research areas defined by the database).

The second search resulted in 82 journal articles referring to additive manufacturing and 66 journal articles describing 3D printing. Among these, 34 journal articles overlapped, leading to 114 unique publications. In the analysis, these journal articles were combined with the result of the initial search meaning that a total of 116 journal articles were analyzed (thus representing an overlap of four articles between the searches). To verify the search result, complementary searches were performed in the databases Scopus and Business Source Premier. Although these searches captured additional publications, the publications were excluded based on the low ranking of the journals or were news items, and similar (and not journal articles).

The 116 articles were analyzed to figure out what assumptions were made about additive manufacturing/3D printing in relation to companies and their management, how the business/management scholars linked to the technological side of additive manufacturing/3D printing, and whether and how the scholars described a process of change, current business models (or parts of business models), or completely new actors and business models entering into a business sector, thus implying a remodelling also on the industry level. More specifically, the journal articles were classified into whether they concerned key resources, key partners, key activities, the value proposition, customer relationships, customer segments, channels, revenue streams, or cost structures. The changes to these were then discussed in terms of changes to content, structures and governance mechanisms as extracted from the different parts of the business models (Zott & Amit, 2010). Appendices 1, 2 and 3 present the articles reviewed and their classifications and content specifications.

Findings

Frequencies

Figure 2 illustrates the frequencies of journal articles per search term (additive manufacturing, 3D printing, or both combined) and by year. As indicated by the figure, there has been a steep rise in the number of journal articles on additive manufacturing and 3D printing during the past few years. Although the data includes few articles published before 2014, it nonetheless suggests that the frequent use of 3D printing as a keyword is a recent trend.

Figure 2. Frequency of results for each search term by year

In terms of the types of journals, most of them have a strong technology/innovation or operations management orientation, with Journal of Manufacturing Systems (17 publications), Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management (14 publications), International Journal of Production Research (10 publications), and Technological Forecasting and Social Change (10 publications) dominating. The type of journals is partly reflected in the key research areas, which focus on the way a company’s offering is produced (key resources and key activities) rather than the value proposition or sales/customer side of the business model, as discussed below.

Business models in additive manufacturing

As Table 1 reveals, most of the journal articles concern the providing side (key partners, resources, and activities) of the business models (77 journal articles in total), with the main emphasis on key activities (42 articles), seconded by key resources (29 articles). These articles concern such issues as how manufacturing is or should be organized with additive manufacturing, the comparison between traditional and additive manufacturing (Achillas et al., 2015), or descriptions of a specific manufacturing process (Zhao et al., 2017). Additionally, several of these articles only refer to additive manufacturing as one of several technologies affecting the future development of producing firms (Hoover & Lee, 2015; Mortara & Parisot, 2016; Pisano et al., 2015).

Table 1. Key themes by year

| Theme | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total |

| Key partners | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 | ||||||

| Key activities | 1 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 42 | |||

| Key resources | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 29 | |||

| Value proposition | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 13 | ||||

| Customer relationships | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| Cost structure | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||||||

| Revenue stream | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Policy/societal level | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||||||

| Not in focus | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 14 | |||||

| Total | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 22 | 33 | 47 | 116 |

As for changes, it is mainly the key activities that are expected to change due to the introduction of additive manufacturing. Mavri (2015), for instance, describes how the production chain changes due to additive manufacturing. Ben-Ner and Siemsen (2017) and Laplume, Petersen, and Pearce (2016b) include the change of supply chains in this regard, describing the shift from global to local, and from long to short supply chains. While not being very specific about the changes of “who does what”, articles by Ben-Ner and Siemsen’s (2017) and Laplume and colleagues (2016b) indicate a change of governance (cf. Zott & Amit, 2010), whereas Mavri (2015) and most other articles focusing on changes to production concern the change of content (activities pursued; cf. Zott & Amit, 2010). This also means that additive manufacturing would foremost be seen changing internal processes of the firm, also indicated by the quite limited number of articles (six) focusing on key partners. The articles concerning key partners mainly describe platforms or communities for design, examine technology transfers from universities, or emphasize the difficulties for small firms to adopt the technology (Birtchnell et al., 2017; Flath et al., 2017; Samford et al., 2017; West & Kuk, 2016). The limited attention paid to key partners implies that additive manufacturing would not require any major changes to core competences of firms or the companies would be equipped to change their current competences to fit with future needs. Related to this, is an acknowledgement of how additive manufacturing could expect to create disruption for certain companies along the supply chain (Mohr & Khan, 2015).

As for key resources, the discussion in the literature focuses on such issues as intellectual property rights (Gardan & Schneider, 2015; Kurman, 2014; Steenhuis & Pretorius, 2017), manufacturing issues and printer choices (Dwivedi et al., 2018; Elango et al., 2016; Paul & Anand, 2015), skills and (financial) support systems, and how new structures may be produced using additive manufacturing (Gardan & Schneider, 2015; Vongbunyong & Kara, 2017; Zhao et al., 2017). While partly concerning changes to resources (such as new skills or changes to intellectual property rules), most articles on key resources describe quite a static view, also not indicating any changes to content, structures, or governance (Zott & Amit, 2010).

As for the offering, 13 journal articles concern value propositions (cf. Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). These include the type of products produced through additive manufacturing: rapid prototyping and innovations, for instance (Berman, 2012; Maric et al., 2016; Rayna & Striukova, 2016; Salles & Gyi, 2013). Rayna and Striukova (2016) make an overview of various offerings and the incremental or radical change they describe, and Laplume and co-authors (2016a) illustrate how small firms use 3D technology in their offerings. Others link additive manufacturing to business performance or business impact more generally (Niaki & Nonino, 2017; Rylands et al., 2016), or describe how incumbent firms would react to the entrance of 3D technology or 3D-printer firms (Hartl & Kort, 2017; Kietzmann et al., 2015). The articles concerning the value propositions broadly defined partly point at changed governance (Zott & Amit, 2010) as new players may enter, but mostly indicate an increased number of practices and thereby offerings enabled through additive manufacturing.

As for the sales side, only three journal articles could be seen to concern customer-related issues, then focusing on customer relationships or changes to them. Rayna, Striukova, and Darlington (2015) discuss co-creation with customers in relation to 3D printing. Christopher and Ryals (2014) introduce the idea of demand chains to emphasize how additive manufacturing means customization and how ideas are pulled by customers rather than created by manufacturers and pushed onto customers. Appleyard (2015), lastly, reflects on piracy music as a means to understand 3D as a process owned by consumers. Thus, the limited literature on the sales side indicates how customers increase their influence and activity on what is produced, thus implying a change in governance of ideas (Zott & Amit, 2010), or “who does what”.

The cost structure is discussed in four articles focusing on the analysis of total costs of production or a change in the cost structure with printers being expensive, while the cost of producing low series is less so (Baumers et al., 2016; Baumers et al., 2017; Manogharan et al., 2016; Tsai, 2017). As for revenue streams, Weller, Kleer, and Piller (2015) discuss revenues related to entry barriers and point at how additive manufacturing may lower entrance barriers, thereby impacting competition and revenues.

In addition to those articles that could be linked to any part of the business model, there are a few journal articles focusing on the societal and policy level, along with a total of 14 articles having 3D printing as one of several empirical examples, while not giving the technology or its business impact any focus.

Summary of results

To summarize the findings, most journal articles thus concern the providing side of the business model, often with an internal manufacturing focus. Optimization is discussed either including changes to activities or meaning that 3D printing is a technology used in processes similar to those of traditional manufacturing. Little suggests knowing about changes to structures (cf. Zott & Amit, 2010), whereas key activities are linked to potential activity changes, and key resources are linked more to static descriptions. The discussion on key partners is limited, where supply chain discussions are quite general while not describing partnerships. Notably, the literature seems to imply that the companies in their internal processes are expected to adjust their core competences to new production methods, rather than link these to partnerships. Value propositions describe various offerings enabled through additive manufacturing, focusing on innovations and prototyping mostly, whereas the literature on the sales side/customer-related issues concerns the increased involvement of customers, implying a possible shift in power (cf. Öberg, 2018) to the customers’ advantage. Discussions on change in business models or their parts focus on some changes to content (activities) related to production, and some few examples of changes in governance (who does what) in supply-chain structures and the shift to customers’ activities, whereas the structures (the links among activities), and thereby the holistic business model influence of additive manufacturing does not seem to be described in previous research. Early articles seemed to be more prescriptive about what would happen, while more recent ones are more questioning to 3D printing/additive manufacturing.

Conclusions

This article summarizes current knowledge on additive manufacturing within management and business research, which leads us now to a discussion of future research directions in relation to business models for additive manufacturing. The literature review indicates a continuous focus on production issues also in the business and management literature. There is an indicated shift from positive connotations to increased questioning of the entrance and meaning of additive manufacturing in the production systems of tomorrow. There is also, when describing how business may change, the tendency to relate to parallel developments in business: the co-production and increased fuzziness between producers and consumers as crowds and communities affect design and production procedures (Ebner et al., 2009; Gulati et al., 2012; von Krogh et al., 2003) that would not be the direct consequence of additive manufacturing.

In terms of business models, what is rarely considered are changes in key partners, entirely new type of offerings, or revenue streams. What is also not considered is how individual companies, given their supply chain position, change or need to change their positions but also competences to meet those challenges and opportunities that additive manufacturing may bring about (Shams & Öberg, 2017). Changes to how various activities are linked are seldom described, which could imply that additive manufacturing is viewed from the lens of traditional manufacturing. And, empirical data beyond measurement in calculations of internal company optimization of manufacturing is rare.

A research agenda for additive manufacturing and business models

Studies on additive manufacturing and its impact on business models are thus scarce, and there is a need to further explore the area and its many different aspects. Specifically, more empirical work is needed, moving knowledge away from scenarios and into how 3D printing in fact affects current businesses on the company level. The following research streams are suggested:

- Research on value propositions and customer-related issues. This would include how offerings are presented, decisions on channels and segments, and their consequences for firm performance. The holistic view including all parts of the business model and how various business models affect the performance of the firm in relation to additive manufacturing would also be important to study, as would the focus on structures (links among activities, cf. Zott & Amit, 2010).

- Research focusing on how individual firms based on their present roles as manufacturers/suppliers, logistics providers, and business customers would change or need to change their roles so as to fit with additive manufacturing. Such research would include the study of various companies as units of analysis and how additive manufacturing would lead to new business opportunities, or constrain current ones. Depending on the company’s position in the supply chain, the vulnerability to additive manufacturing would differ, and the studies could compare companies based on their various supply-chain positions, while thus focusing on the company level.

- Research on the effects of parts, tooling, and prototyping. This would include how companies at various supply chain position would be affected by, take on, and also potentially try to move into more lucrative positions as, for instance, part manufacturing would be insourced by other companies. Comparisons could here be made among companies at each position for the effects of parts, tooling, and prototyping, respectively.

- Research on what competences are needed as companies adapt to additive manufacturing and depending on the company’s current role. Competences would not only include those of additive manufacturing, but also competences on how offerings could be created, and they may well mean that a company manages to keep its position based on specific competences, while it would otherwise be challenged by the additive manufacturing. Competences should ideally be studied over time to see how requirements of them change, and how companies develop and adjust them. The role of key partners and thereby structures and governance would be important to study in relation to competences.

- Research into how payment models should be designed to minimize financial risks, while also taking into account the high investments of additive manufacturing. The payment systems and price strategies of today traditionally focus on how a customer pays the supplier for products delivered. In multiple-party systems, and if competences become a key concern, the way and for what payments are made could expect to change and create new and more creative business models.

- Research taking a deeper look into customer interaction from the perspective of home-based production. While it is important to contextualize any development, it is also important to study the customer interaction as an isolated activity (that is, not in conjunction with, for instance, community trends) so as to understand how roles and powers are changed for parts, tooling, and prototyping, respectively.

- Research into additive manufacturing/3D printing using different materials. Most studies concern plastic materials, and it would be important to compare how various materials change the business models of companies in similar or different ways. This would include comparing plastics with metal printing, for instance, in how they would cause changes to business models of companies.

Comments: This article showcases the possible business ventures that can come out of additive manufacturing. I data displayed allowed me to get a good understanding on how this business can prosper in the future.