By Allison Colburn

April 4, 2016

Published by The Columbia Missourian

COLUMBIA — Angie Zapata calls the palette of intense reds, blues and greens on Latino children’s book covers “artesanía,” a word used in Mexico to describe traditional folk arts and handicrafts.

Zapata, an assistant professor who teaches and researches literacy education at MU’s College of Education, has studied diversity in children’s literature since she started teaching in 1997. When she thinks about why she loves the field, she recalls a day she was teaching children’s literature to undergraduates. She had covered one of the classroom tables with Latino children’s picture books. When one of her students walked in and saw the kaleidoscope of colors, she said she felt like she was home.

“Literature can serve as a mirror into our own lives,” Zapata said.

It can also be a window into different lives.

“The color palette, the language, the stories are hooks,” Zapata said. “They’re little ties that bind us to step into new worlds and new ways of knowing.”

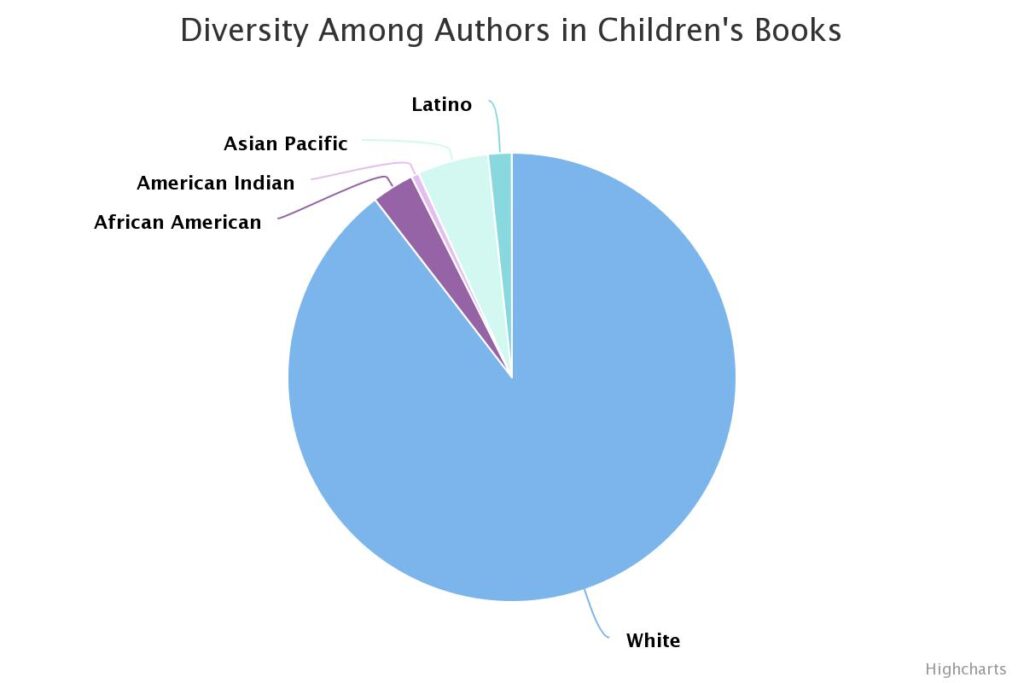

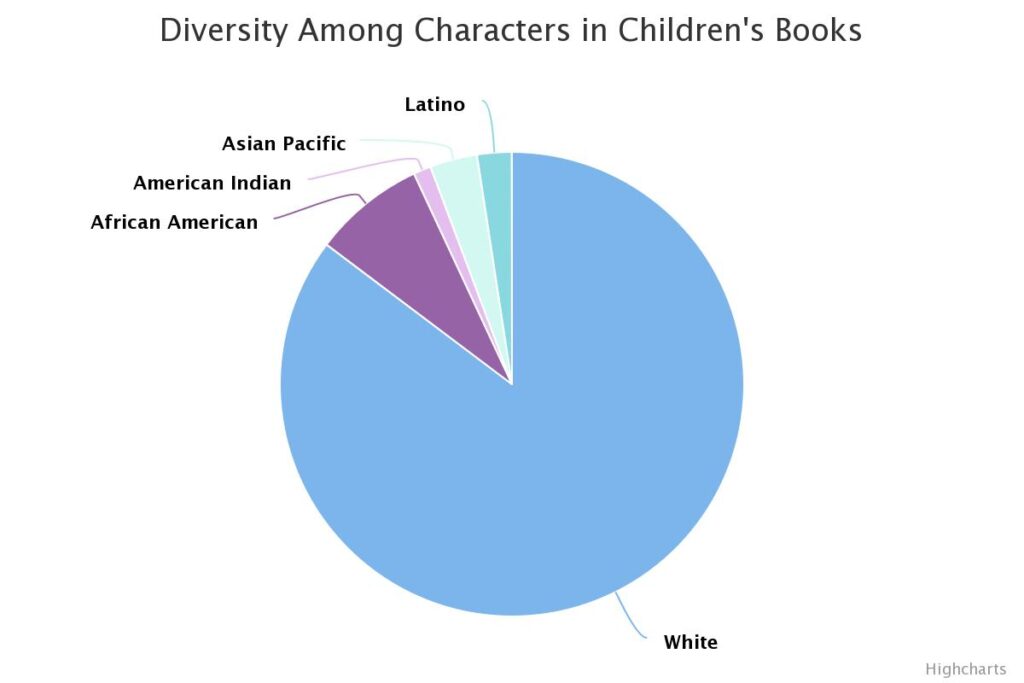

Statistically, children’s literature tends to look into a not-so-diverse world. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin estimates that in 2015, about 10 percent of children’s book authors and 15 percent of the books’ characters were African-American, American Indian, Asian Pacific and Latino. Meanwhile, close to half of American children were not white, according to a 2014 census report.

The tendency in the children’s book publishing industry to cater to white children is not new and there have been calls for change for decades.

In Columbia, public school librarians are working to provide diverse book collections so that minority students feel reflected in literature. Librarians also want white students, who comprise 62 percent of the student body in Columbia Public Schools, to see backgrounds different from their own.

Nationally, activist groups are speaking out against industry bias and hoping to make widespread change.

Local initiative

Kerry Townsend, media specialist coordinator for the Columbia district, said that this year, as part of a larger district initiative to address the needs of all students, school librarians have focused on providing a more diverse book collection.

Townsend said administrators recently participated in a book study of Robert Putnam’s 2015 “Our Kids,” which looks at the growing “opportunity gap” among children in the U.S. She said that after reading the book, she felt she could help the initiative by encouraging librarians to provide stories for and about children who are not from a white, upper-middle class background.

“The practical reason we are doing this is because we want our students to read,” Townsend said. “And they’re more likely to pick a book up if they can find something that speaks to them.”

In that sense, books are mirrors. But it’s also important that they be windows. Sarah Easley, the librarian at West Boulevard Elementary School, said it’s important to keep both in mind.

“I think everyone benefits from both being able to see themselves in a character and to be able to identify with a character that is totally different from them,” Easley said.

Smithton Middle School librarian Anthony Strand agrees.

“A book puts you inside someone else’s head,” Strand said. “Subconsciously, I think that helps you understand their perspective, and I think that makes for more empathetic people in the long run.”

Problems in publishing

But barriers in the publishing industry are making it difficult for readers and librarians to find diverse books.

Lorelei Donaldson, the librarian at Blue Ridge Elementary School, thinks it’s important for children to envision minority faces in literature’s leading roles, which might translate into more prosocial behavior. She wants to provide books with a wide range of characters for her students, but she doesn’t have a lot of options.

“If you look at kids’ books that are published, the vast majority are either animals or white, middle-class kids,” Donaldson said. “It’s really hard to find a good-quality, authentic book that would maybe reflect other experiences.”

Her frustration with a lack of diversity is not new. More than 50 years ago, in a 1965 article in the Saturday Review, Nancy Larrick criticized the mainly white landscape of children’s literature.

“Integration may be the law of the land, but most of the books children see are all white,” wrote Larrick, founder of the International Reading Association.

Larrick had sampled more than 5,000 children’s books and found that 6.7 percent included black characters. By comparison, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center found that last year, just 7.8 percent of children’s book characters were black.

“There seems little chance of developing the humility so urgently needed for world cooperation, instead of world conflict, as long as our children are brought up on gentle doses of racism through their books,” Larrick wrote back in 1965.

In recent years, national campaigns to change the children’s book publishing industry have called attention to the lack of minority representation in books.

In January, Scholastic Publishing stopped distributing “A Birthday Cake for George Washington” after an online backlash. The book was about George Washington’s household slaves, who were depicted as joyous and smiling, prepping for the president’s birthday celebration.

“Without more historical background on the evils of slavery than this book for younger children can provide, the book may give a false impression of the reality of the lives of slaves and therefore should be withdrawn,” a statement from Scholastic said.

The statement also said the company is committed to providing diverse literature. As a response, an online petition organized in February by American Indians in Children’s Literature, the Ferguson Response Network and Teaching for Change quoted Scholastic’s statement and called for the company to do more.

“We are glad that Scholastic recalled the #SlaveryWithaSmile book and has published a few new middle school titles by and about people of color and Native Americans, but there is much more to be done,” the petition said.

On the last day of Black History Month, Feb. 29, Scholastic teamed up with the nonprofit We Need Diverse Books, which works to make the book publishing industry more inclusive. The two organizations announced Scholastic would begin distributing Scholastic Reading Club fliers in schools to advertise books representing diverse races and ethnicities, religions, LGBTQ characters and characters with disabilities.

We Need Diverse Books started in response to an announcement for a 2014 BookCon event in New York where a panel of all-white and all-male speakers was set to speak on behalf of the children’s book industry. Similar to ComicCon, BookCon is an annual celebration of literature that includes panels of speakers and representatives from the publishing industry.

More than 20 children’s authors and literature advocates engaged in a conversation over Twitter with the hashtag #WeNeedDiverseBooks. This garnered a large online response, according to Stephanie Sinkhorn, a spokeswoman for We Need Diverse Books.

“Most children’s literature authors, first of all, are female,” Sinkhorn said. “So that stood out right away.”

Then there was the fact that the panelists were all white — which represents the publishing industry as a whole. It’s a disproportionately white field, Sinkhorn said, and that makes it harder for authors of other races to get the same attention and marketing as their white counterparts.

“It’s far more difficult for diverse authors to get published if their voices aren’t represented in the publishing industry,” Sinkhorn said.

In response to the criticism about the panel, Ellen Oh, president of We Need Diverse Books, was invited to arrange a panel. Sinkhorn said it drew such a large crowd that the room was overcapacity.

The demographic makeup of the children’s book publishing industry was explored last year by Lee and Low Books, a multicultural children’s book publishing company established in 1991. It found that 79 percent of people who work in the industry were white. Book reviewers, who tend to influence what readers buy, were 89 percent white.

Hannah Ehrlich, a spokeswoman from Lee and Low Books, said racial and ethnic disparities are not just contained to the publishing industry. She cited similar issues in the movie industry as an example.

“It helps to think of it more as a symptom, rather than something contained to the publishing industry,” Ehrlich said. She added that the stakes are especially high in the children’s book industry.

“Children are still learning and absorbing everything,” she said.

Source: https://www.columbiamissourian.com/news/k12_education/increasing-diversity-in-childrens-books-still-a-challenge/article_6cafb600-ed49-11e5-92b8-8bbea608e339.html

Comment: This article points out the large lack of diversity in children’s book characters and in children’s book authors. The article brings up the important point that kids are more likely to pick up a book if they resonate with it and it speaks to them. In this way, creating a more diverse set of books in schools or libraries is a way to start catering to minorities who already may have other disadvantages when it comes to learning to read. A friend of mine recently started a GoFundMe page to fundraise money to buy her old elementary school new diverse children’s books. That definitely relates with what this article is getting at and shows that it takes initiative and motivation to bring a diveristy of books into schools and even in publishing.

When I was browsing the LFL site, they recently started an initiative called “Read in Color” where they have emphasized books with authors and characters who are POC and BIPOC. They also push to have mini book clubs within a community to discuss topics on diversity.