By Benjamin Mosher – Sept 22, 2020

Introduction

The topic of Access vs. Ownership as a duality existing within modern society, carries with it a great deal of nuance that spans a variety of research disciplines. While I approached my inquisition through a designer lens, the content of my findings ultimately concerned themes in behavioral economics, consumer psychology, and market analysis as it relates to the shared economy. These topics of interest carry immense opportunity for exploration, as consumer behavior will undertake a dramatic shift following the COVID-19 crisis. My initial concerns dealt with the effect the pandemic would have on the shared economy, as it is an increasingly popular economic model for its benefits in providing accessibility and the potential for sustainable business practice.

Given the unprecedented reorganization of social structure and human interactions resulting from such a far-reaching public health crisis, it is inevitable that community-based economic models will be directly affected. As these economic models provide promising outlooks for more sustainable and equitable business patterns, it would prove detrimental for product designers to fail to adapt and respond accordingly. By understanding how industrial design can respond to these changes, we can begin to augment and inform consumer behavior in a way that proliferates an access-based product and consumer ecosystem within a post-COVID context. Taking themes from the behavioral economics field into consideration, my research aims at discovering how product design can be informed to appropriately respond to dramatic shifts in consumer-behavioral patterns, as they relate to access-based economic models.

Social Exchange: A Perspective

As the subject matter is expansive and the stakeholders are essentially anyone that actively participates in the economy, I decided to take a loosely focused, exploratory approach to collecting secondary research. Beginning with the Focus section of my research blog, I sought out to identify a select group of articles and journal writings that were rooted in some of the same critical themes of interest, while approaching from various lenses of focus. In the journal by Jeonghye Kim, Youngseog Yoon, and Hangjung Zo featured in that section, these researchers sought to explore the competitive reasons behind why one might choose to participate in the sharing economy through analyzing it as it relates to the social exchange theory. This theory of sociology explains the concept of risk / benefit evaluation that we experience as a result of interpersonal interaction. Essentially, it is a theory about our risk assessment within various social relationships. In the article mentioned above, this theory is applied to the sharing economy, as it suggests the presence of a transactional exchange between two entities.

While the social exchange theory is most commonly used when explaining social interactions, or “transactions”, it can be applied when understanding the social relationship that is inherently tied to a transactional exchange. The journal directs this train of thinking into the concept of “ownership transfer” as it’s used to explain the traditional economy in contrast to an access-based transfer of value and responsibility. This particular journal stood out to me, as it best summarizes the findings accumulated from the entirety of my secondary-research within each section of the newspaper. The most relevant topic of interest for product designers is the idea of augmenting social exchange in a way that builds value in access based economies, while simultaneously alleviating the “risks” assessed as symptoms of ownership.This concept directed my inquisition going into the first hand research stage.

Research Inquiry

To gather insight on the various topics of interest to come out of my secondary research, I generated an 11 question online survey questionnaire that was sent out through social media platforms, ultimately accumulating 110 individual responses. The main goal of my questionnaire design was to assess a rough understanding of why people behave the way they do with regards to their respective motivations, behavior patterns, and preferences regarding many of the topics I’ve identified thus far. Drawing from my interest in social exchange as it relates to access-based economies, I hoped to gain a broad understanding of the current state of opinion regarding the sharing economy, as well as a general understanding of what people value and prioritize as consumers. It became clear following this course of inquiry that some exploration was to be done regarding the inconsistencies in what people wanted versus what they did.

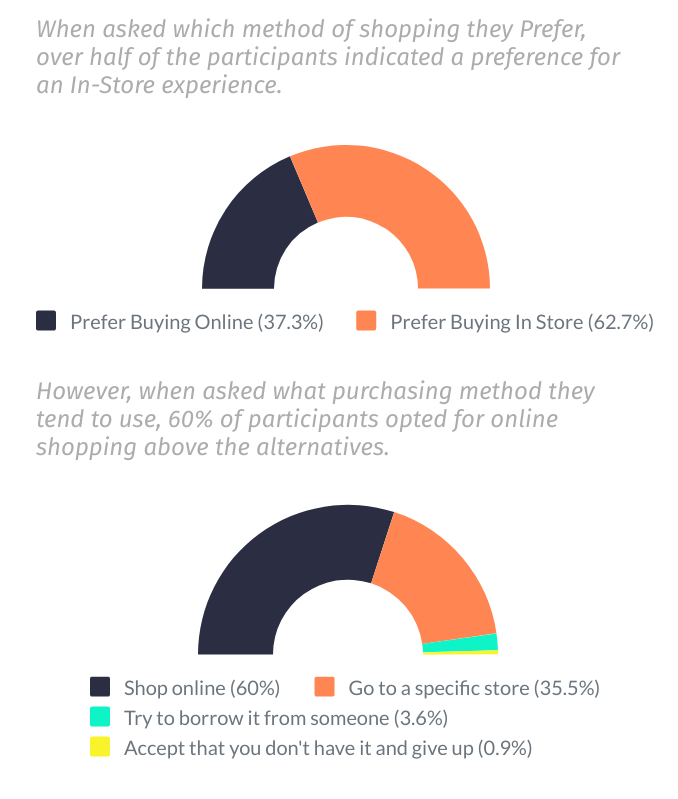

Of the 110 survey participants, nearly 63% indicated a preference for shopping in-store as opposed to buying online. This data point seems rather uncomplicated when looked at in isolation, however, when asked which purchasing method they most frequently use, 60% of the respondents indicated that they shop online most often. Only 35% indicated they most frequently shop in store while the remaining responses were divided between borrowing or opting out of purchasing altogether. With the psychological motivations and elements of behavioral economics as driving forces behind my research inquiry, it became immediately interesting that a large majority of respondents indicated a preference for in-person shopping experience, yet that same majority indicates that they most frequently opt for the online alternative. What accounts for this disconnect between preference and actual action?

I found this question to be informative when conducting my first hand informal interview inquiry. When asked why they prefer to shop in store, a particular interviewee indicated a desire for small business experience with the moral satisfaction that comes with supporting local business. This respondent, a woman in her early 20’s, stated that she feels better about the interaction with local economy and community members that come as a result of purchasing in store. In that same interview, she also indicated that costs were a major determining factor when it came to guiding how she shops; a factor that often came in the way of supporting local, as this type of economic choice tends to cost more than online marketplace alternatives. This further suggests a disconnect between what consumers want out of a buying experience, or social exchange, and the experience they actually resort to for additional external factors. It would appear based off of these observations that there is some intrinsic value rooted in online consumption that results in a sacrifice of the value indicated to be found within in-person shopping experiences. The trend of online consumption is pushing towards an online model, as supported by data cited in the statistical infographic presented in the Numbers newspaper blog. Perhaps this deals with the ease of “access” provided by the internet and online shopping methods.

Access & Ownership

This convenience form of “access” is undeniably attractive to the modern consumer, but how does it relate to the concept of access as we’ve defined it in opposition to ownership? Another male interviewee who self-described as a working professional in his early 30’s, suggested that buying something online felt like the quickest way to “access” the item he needed as soon as physically possible. He seemed to be somewhat unconcerned with what this type of access meant after the need was fulfilled. I continued to question him on the post-purchase, post-use existence the item has in his life, and he expressed an under-considered narrative along the lines of what many Americans experience with the items they own; something to the effect of, “I store it away and I have access to it the next time I need it”. When asked about how this may compound with time and further purchasing, he expressed again that he hadn’t given much thought to the way this pattern of consumption results in a compounding of physical ownership.

Another key part of my secondary research looked at the side effects of ownership, and the American pattern of individualistic ownership and cradle to grave consumption outlined in the paragraph above. A statistic by the LA times states that the average American home contains roughly 300,000 items, while a data point by the U.S. The Department of Energy states that roughly 25% of Americans with a two-car garage don’t have room to park a car due to item storage. These statistics reinforce the narrative outlined by the interviewee above who indicated a pattern of consumption that follows the purchase to use to storage pattern of consumption. This pattern results in financial burden, mental and physical clutter, and unsustainable production as seen in modern product markets. It became clear to me that these are points of leverage that can be used to proliferate a more access-based economic model as an alternative.

Analysis & Outlook

The problem with online shopping is that it results in a consumer ecosystem that promotes quick and cheap ownership as the most convenient means to access. In addition to this model achieving a great deal of buy-in from our convenience based society, we now find ourselves in a global public-health crisis that deters social interaction and interpersonal transactions that often are identified as key aspects of in-store buying experiences. Despite interviewees and survey respondents indicating a preference for this experiential side of consumption behavior, there will be an inevitable apprehension when it comes to face-to-face interaction amidst the COVID-19 crisis. This brings me back to the notion of “social exchange theory” as it relates to risk assessment and analysis of social exchanges and transactional relationships. In order to proliferate an access-based economic mode of consumption, industrial design will need to respond to the drastically evolving state of social exchange economics and consumer behavior as they relate to experience, convenience, and ownership within the context we find ourselves in. In doing this, the designer may be able to re-contextualize the consumers understanding of access and aid in a productive shift away from the “buy with one click” narrative that has become all too familiar in modern society.