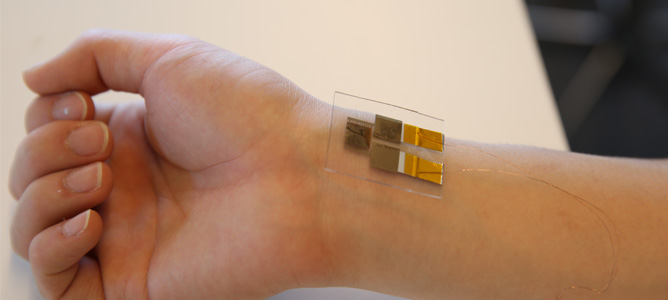

Melbourne researchers have developed a new form of wearable technology that can become part of the body, forming a metallic artificial skin.

The technology, which involves the use of biomedical sensors, was developed by scientists in the NanoBiotics lab at Monash University, for the purpose of monitoring patient health.

Made from an incredibly thin gold thread, ten times smaller than a human hair follicle, the new wearable technology concept could be used to monitor body motion, heartbeat, and blood pressure.

According to head researcher, Professor Wenlong Cheng, the soft electronic skin (or e-skin) can offer applications that are difficult to achieve with rigid conventional wafer and planar circuit board technologies due to its unique capacity to integrate with soft materials and curvilinear surfaces. Dr. Cheng says, “one core challenge [for wearable technology] is that Mother Nature doesn’t provide viable materials allowing for the design of soft electronics”.

During his presentation at CeBit’s eHealth conference in Sydney, Professor Cheng said the dilemma is that the traditional inorganic or organic materials often cannot meet this requirement.

“Rigid and/or crystallised inorganic materials usually have good optoelectronic properties, controllability and stability but their mechanical compliance is generally poor. Meanwhile, soft organic materials often show excellent mechanical flexibility and robustness but poor optoelectronic properties, so we need new eMaterials design rules.”

The ultra-thin piezoresistive materials can withstand 600 percent strain, resulting in a highly stretchy and durable wearable biomedical sensor for real-time health monitoring.

Professor Cheng also noted the fabrication of the technology requires very little cost, is environmentally sustainable, and doesn’t require access to a clean room environment.

The Monash team have been developing various projects on the back of this technology, including the optimisation of an “e-skin NanoPatch” wearable heart health monitoring device, with trial data being collected in a clinical setting. The project has involved collaboration among nanotechnology specialists, electrical engineers, industrial designers and clinicians specialising in cardiac research.

“This form of sustainable nanofabrication will be a key component in future wearable electronics with broad applications ranging from electronic skins, intelligent human/machine interactions, soft robotics, and energy harvesting,” said Professor Cheng.

This article explores the idea of non-invasive blood pressure monitoring through skin patches. Monitoring health patterns is obviously important to overall health. However, most people do not want to take time out of their day to perform personal daily check-ups and measurements. This is especially the case with monitoring blood pressure. Having a skin patch that monitors this data would help with personal monitoring’s ease and time.

However, as we see the market of fitness and health trackers booming, it is important to ask if there is too much interaction with technology among our daily lives. From staring at a computer screen during the work day, to constantly checking our watches to track our calories, to watching TV at night. Although this boom in wearable health technology, is a step in the right direction of personal health monitoring. However, using smart watches and apps only add to our daily screen time. This research project provides an alternative to the screen dilemma by continuously tracking health data in the least invasive way possible.