By Sandra E. Garcia

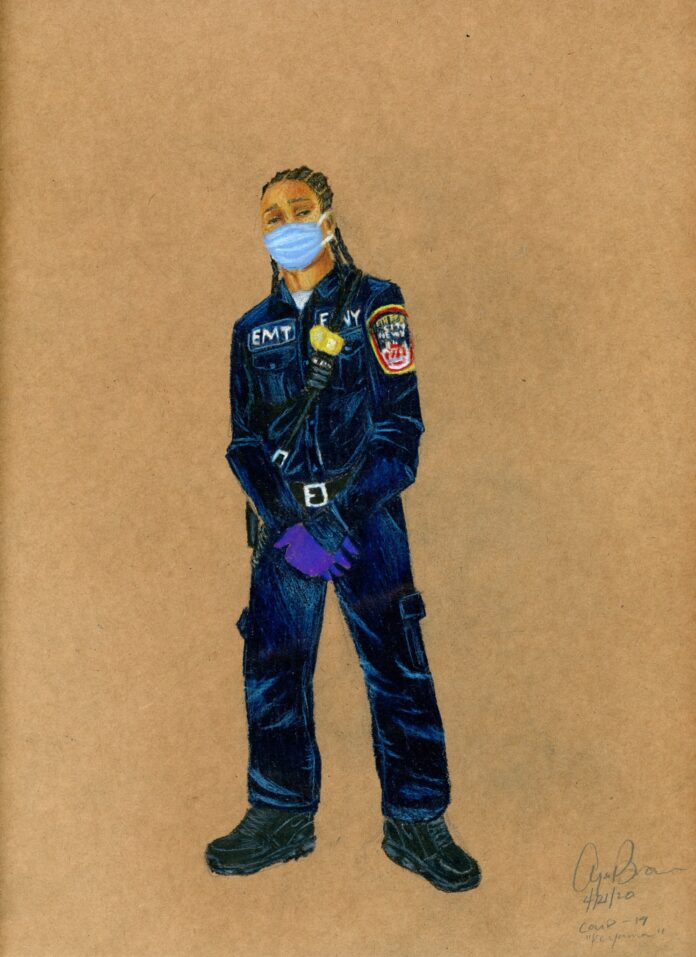

The faces of the women in her portraits are often partly covered by a mask tied behind their heads, tugging at braids, low buns or tufts of curls. They are dressed in uniforms that show their essential jobs, but their style and charisma shine through their everyday armor.

They are Black women who work in jobs that the coronavirus pandemic quickly revealed as essential to the functioning of New York City. And they were all drawn by Aya Brown, 24, a Brooklyn artist. They are women who took care of Ms. Brown during a hospital or a supermarket visit. They include janitors, M.T.A. workers, mail carriers and security guards.

The drawings — made with color pencils on brown paper — comprise Ms. Brown’s Essential Worker series, a collection drawn with an intimacy that makes the viewers feel as if they too know the subject. It’s not just their jobs that are depicted through the lines and colors, but their panache.

“My goal is to uplift Black women who look like me and inspire me — to give them a space to be seen and to bring awareness to them,” Ms. Brown said.

Women have been the heroes of the pandemic. They are in the emergency rooms, on the streets delivering packages, in nursing homes, on construction sites, and many are still teaching their students who have been attending school from home.

One in three of the jobs held by women is essential, according to a New York Times analysis of census data crossed with the federal government’s essential worker guidelines. Most of the women who have essential jobs are women of color.

She began her Essential Worker series in April, after a trip to the emergency room.

“I noticed that nurses in the E.R. are usually Black women,” Ms. Brown said. “I am thinking about these Black women on the front lines. It just bothered me because no one is noticing this.”

Black women are also underrepresented in the worlds of art and media, and Black queer women are nearly nonexistent in museums, according to Chaédria LaBouvier, the curator of “Basquiat’s “Defacement”: The Untold Story,” at the Guggenheim Museum.

Ms. LaBouvier said Ms. Brown’s work is not about being left out of the white, heterosexual, patriarchal art world, but about the Black working class saying, “I am already the center, and there is a lot of beauty here.”

Ms. Brown’s work “looks at what liberation actually could be,” Ms. LaBouvier said. “You’re in a moment where queer women are saying, ‘It is so much bigger than fitting into the system; let’s abolish the system.’”

According to Ms. Carter, when we look back on this moment in history and wonder who saved New York City from the coronavirus pandemic, Ms. Brown’s portraits will provide the answer.

“Who she’s making the art for seems to be just as important as the art itself,” Ms. Carter said. “Art made with that kind of love and rigor is self-evident and can’t be co-opted.”

Garcia, Sandra. “How a Brooklyn Artist Is Making Black Women Her Focus.” The New York Times. July 6, 2020.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/06/nyregion/black-women-essential-workers.html

Analysis–

This was an interesting article about Aya Brown and her illustrations of Black woman working in essential fields. Her illustrations of these women are intimate and uplifting as they show these strong women working to protect and save New York City and its people. Brown’s illustrations also give representation to Black queer women, who have been extremely underrepresented in media and art. I think her work is extremely powerful and uplifting. And this is necessary in these times. Who says art can’t be useful during a pandemic?

I find Brown’s work to be relevant to my research because it supports essential workers, especially the most underrepresented and underappreciated groups of people: Black and Black queer women. I think this article would act as a good reference when designing for my finalized thesis topic. It will act as a reminder to address the needs of women and I hope to be able to gather insight and potentially speak with Black women and Black queer women working in the transportation sector.