This article gives a big picture overview of the situations of students and teachers towards the end of the spring semester as a result of COVID-19. The points that stood out to me the most was the decrease in communication between teachers and students, and the widespread lack of participation of online classes. If children don’t have a caregiver who is wlling and able to support their schooling at home, it is very difficult for children to have a quality education.

—

Kurtz, Holly. “National Survey Tracks Impact of Coronavirus on Schools: 10 Key Findings.” Education Week, 10 April 2020, https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2020/04/10/national-survey-tracks-impact-of-coronavirus-on.html.

“The disruption in K-12 education due to the coronavirus is way more than anyone could have imagined just a couple of months ago. A system that has relied primarily on face-to-face interactions in school buildings for generations is now operating almost entirely virtual. That big, rapid shift has dampened morale among both teachers and students, and it has exposed huge equity problems in K-12 schools.

“At the same time, it has forced educators to learn how to use new technologies, such as video conferencing, very quickly. That rush to use new technologies, though, opened the doors for a wave of data privacy and security problems, especially with the wildly popular Zoom videoconferencing platform.

“Following are 10 key insights from our most recent survey, a nationally representative, online poll of 1,720 educators administered April 7 and 8.

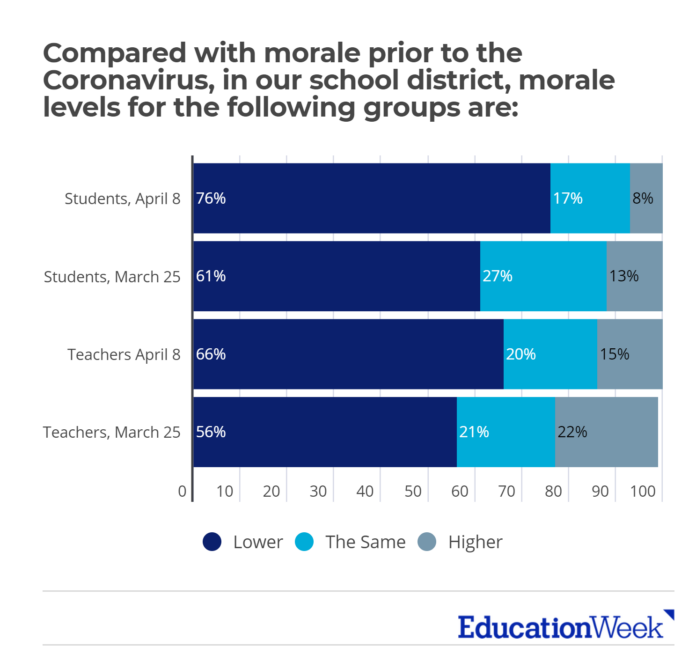

1. Student and teacher morale are down.

“the reality is that student and teacher morale is suffering (as reported by teachers and district leaders), declining considerably between March 25 and April 8.

“There are multiple possible reasons for the declines. Teachers and students miss seeing each other every day. (Morale among teachers is especially low in elementary schools, which are more likely to cultivate a family-like environment.)The rituals of school—from mundane daily routines to milestone celebrations like prom and graduation—have suddenly been struck from the calendar. Teachers worry about the challenges and inequities that their students will face when the supports that schools provide are that much harder to access.

“‘This is a serious loss for both students and teachers,’ Kathleen Minke, the executive director of the National Association of School Psychologists, told Education Week in a recent story. ‘When you experience those kinds of loss, it is perfectly reasonable, acceptable, and human to feel grief around that.’

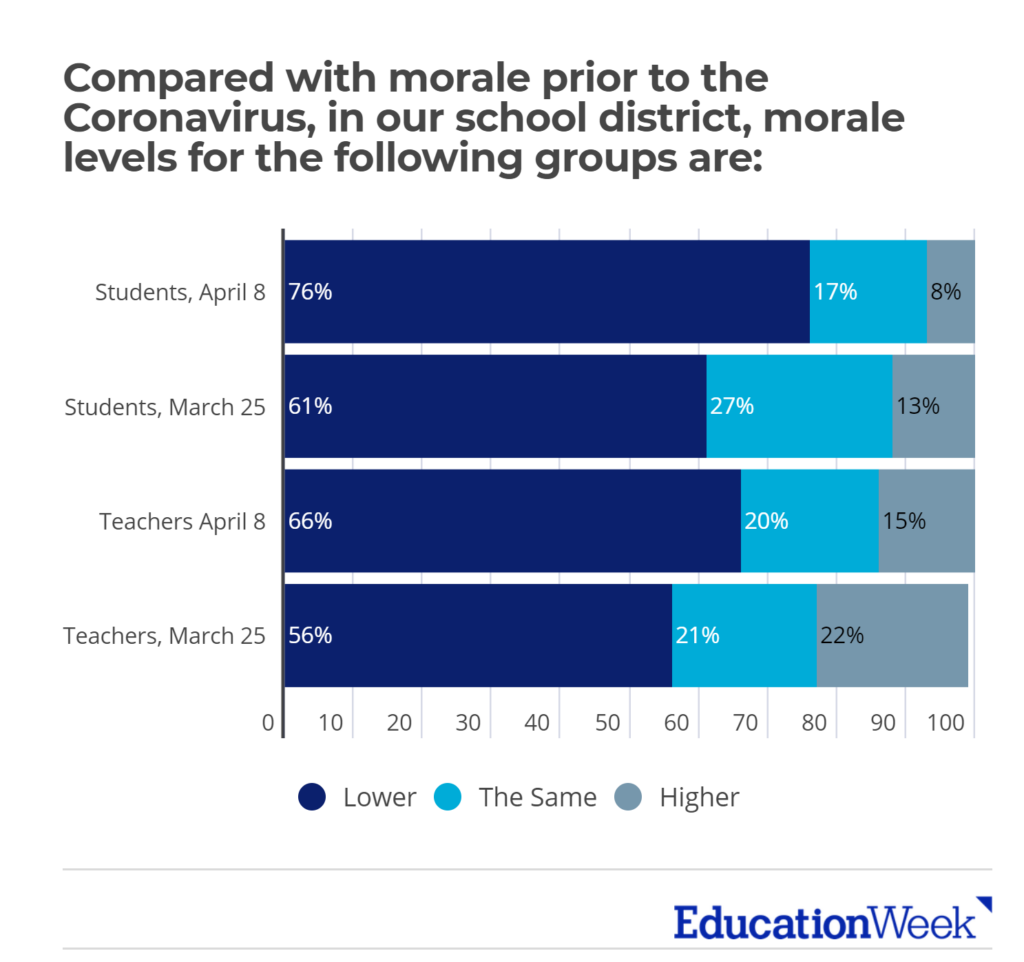

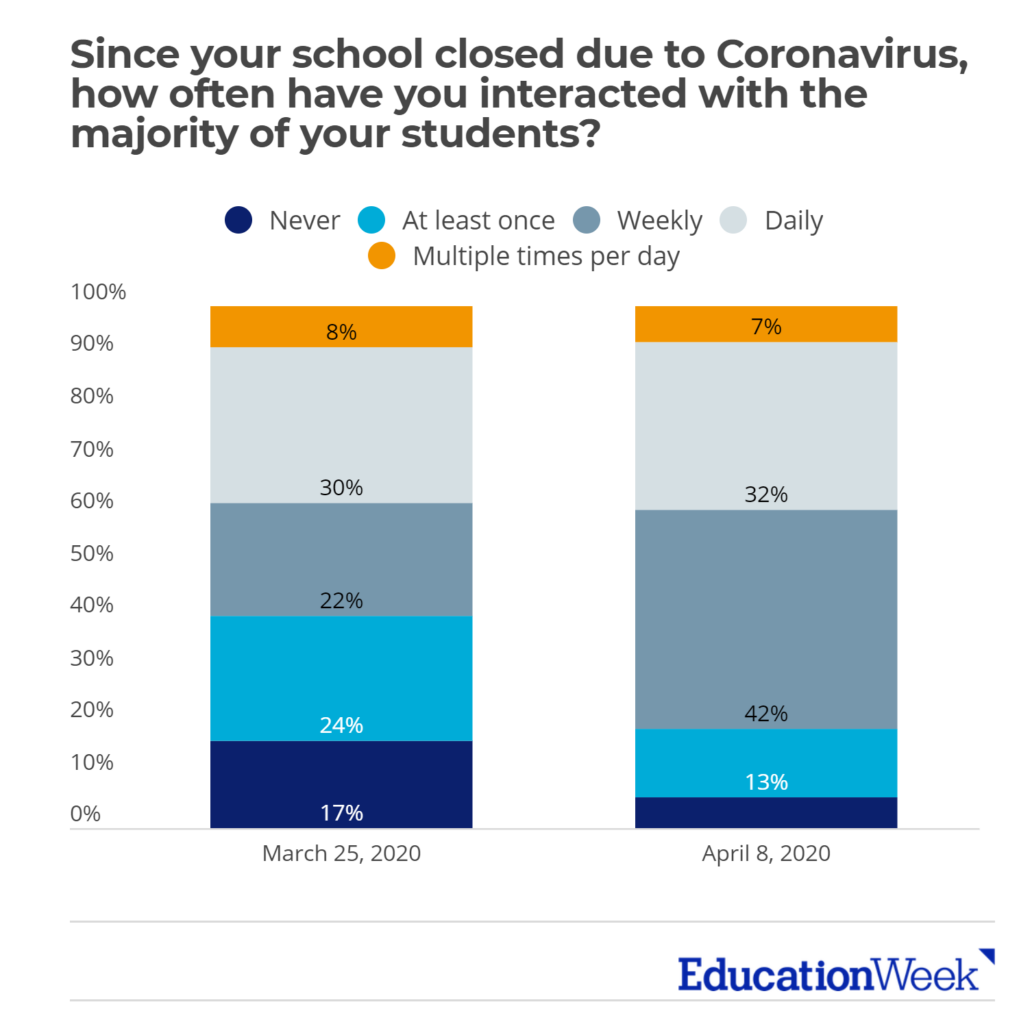

2. Teachers say they’re spending more time on instruction and communication. But equity problems persist.

“nearly all teachers (90 percent) say they are engaging in instruction now, compared with 74 percent in late March. Teachers are also engaging in more communication with students.

“That said, some students are having more contact than others.

“More than half of teachers (56 percent) in lower poverty districts (with poverty rates under 25 percent) are interacting with their students at least once a day, compared with about 1 in 3 in districts in which three quarters or more students come from low-income families.

“Science teachers and elementary educators who teach all subjects report the highest levels of daily contact. Special education and arts teachers report the lowest.

“Woods said he tries to pay particular attention to those kids who might be facing very difficult circumstances.

“When a kid says, ‘My mom doesn’t have a job and there are four of us, and she’s alone and I’m worried.’ That’s somebody I want to pick up the phone and call, and somebody’s mom I want to email,” he said.

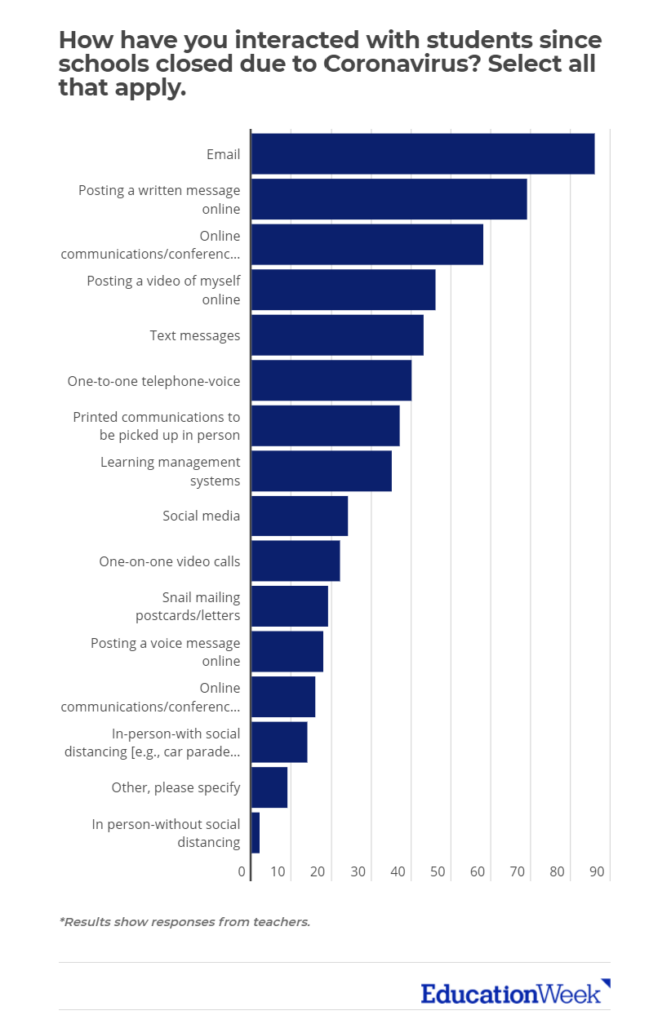

3. Email is the most common form of teacher-student interaction. Videoconferencing is also popular.

“More than 1 in 5 elementary teachers (but just 6 percent of high school teachers) have communicated with their students in-person, with social distancing, through car parades, neighborhood wave-and-walks, and other approaches.

“Emily Richley, a 5th grade teacher at Dennis Elementary School in Springboro, Ohio, told Education Week that video-chatting with students, being able to see their faces, has been important for building community. She hosts chats on Google Meet throughout the week. It helps her connect with the kids, but also gives them a chance to see each other.

“‘They miss each other,’ she told Education Week. Her 5th graders show each other their dogs or introduce the class to their siblings. ‘In a way, it has made the community a little more personal, because we’re almost meeting in each other’s homes,’ she said.

4. More than a fifth of students are not participating in school, with larger truancy rates in high-poverty communities

“Even as teachers amp up communications and instruction, they report that, on average, 21 percent of their students are essentially ‘truant’ during coronavirus closures (not logging in, not making contact, etc.)

“The percentages are highest among districts in which more than three-quarters of students are from low-income families. Nearly 1 in 3 students in those communities are not participating in remote learning, compared with 12 percent in districts in which a quarter or fewer students live in poverty.

“Given that income is strongly associated with opportunities to learn, this means that the students who are most likely to need it most may be receiving the least instruction, opening up the possibility that closures will widen existing equity gaps.

“’These students were distracted from their world by coming to this building that was outside of the community where they faced all these barriers,’ Jones said. ‘Now, they’re stuck at home in that chaos. Who can really expect some of these students to do that [academic work packet] when they’re at home starving or they’re at home taking care of their siblings?’

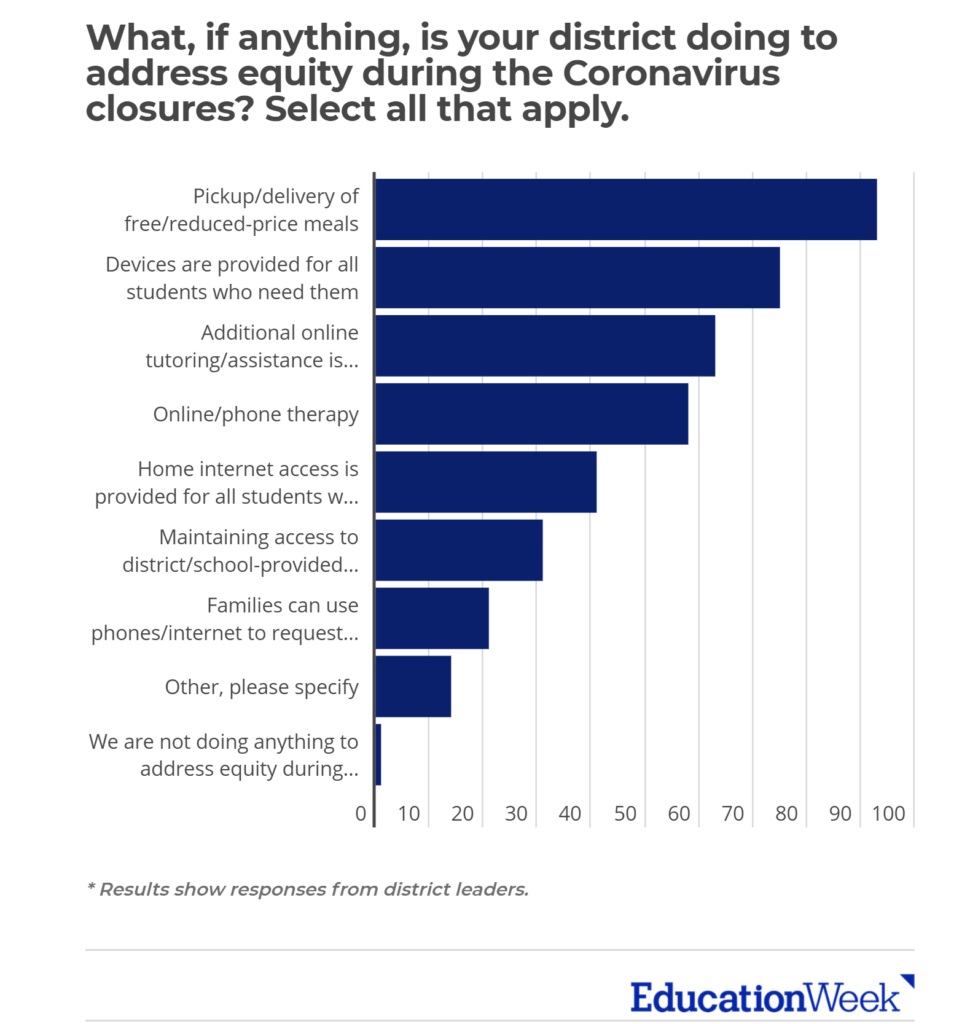

5. District leaders are trying to address equity

“Ninety-nine percent of district leaders say they’re at least doing something to address equity during closures.

“Offering pick-up/delivery of free or reduced-price meals is the most common measure. A majority of administrators also say they provide devices to all students who need them, make additional online tutoring available, and provide online/phone therapy.

“Unfortunately, these efforts are not necessarily reaching the students who need them most. For example, 62 percent of leaders in districts with poverty rates under 25 percent say everyone who needs home internet access gets it. Among leaders in districts where poverty rates exceed 75 percent, the rate is roughly half that amount (31 percent).

“In fact, the coronavirus has exposed the digital divide that exists in K-12 schools. In response, many urban districts are scrambling to purchase digital learning devices such as Chromebooks and iPads so that students without those technologies are not left behind. Other districts are outfitting school buses with WiFi hotspots and locating them near apartment complexes to help students get access to the internet.

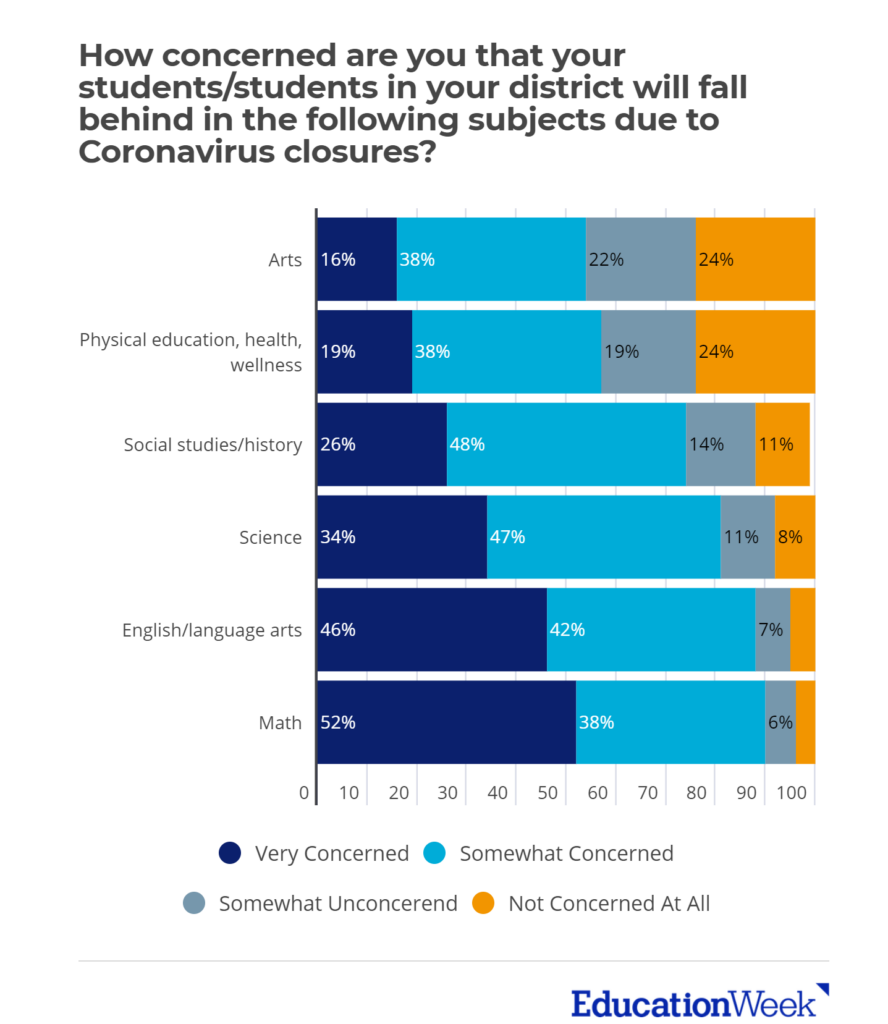

6. Educators are most concerned students will fall behind in math

“Educators are most likely to be very concerned that students will fall behind in math during school closures, although English/language arts is a close second.

“However, math teachers are concerned that students having difficulty understanding certain concepts will not be able to get the one-on-one attention they would usually receive in a regular classroom. As a consequence, kids who struggle with math might fall further behind during school closures.

“Additionally, across the board, in every subject included on the survey, educators in higher poverty districts are significantly more likely to be concerned that students will fall behind. For example, two thirds of educators in districts where three quarters or more students live in poverty are very concerned that students will fall behind in math as compared to 38 percent of those in districts with poverty rates of 25 percent or less.

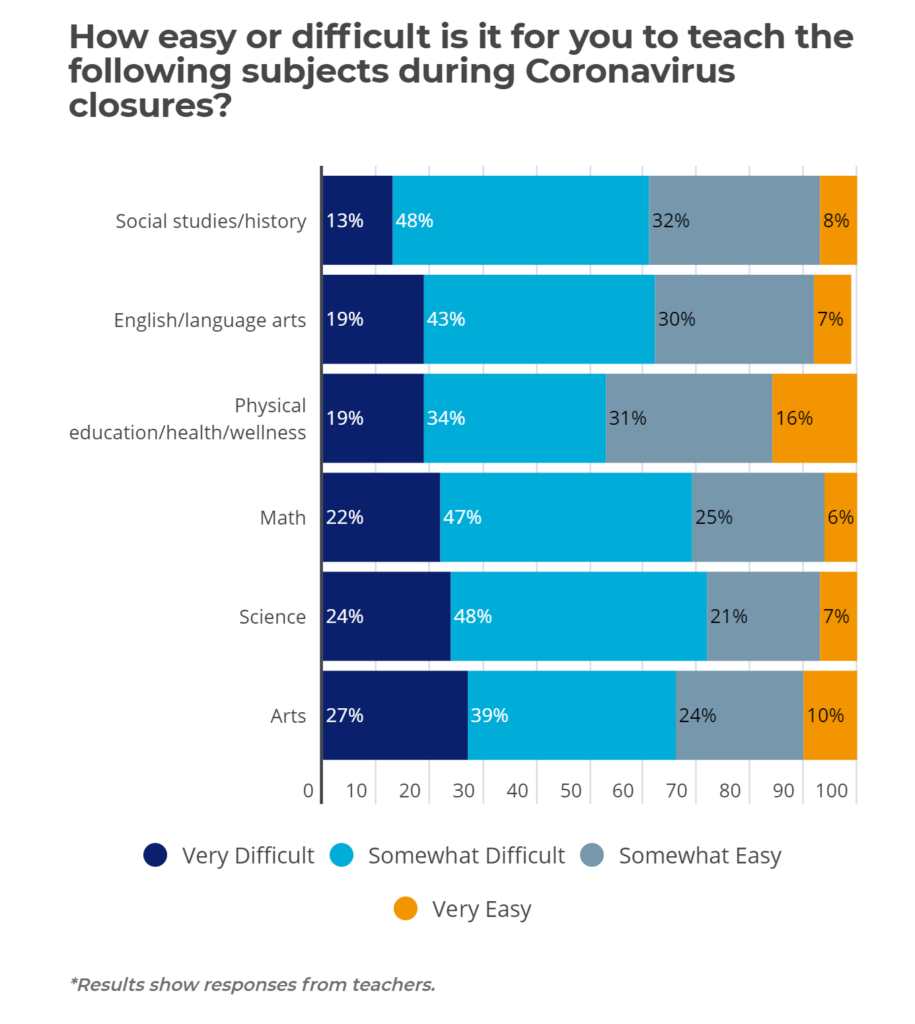

7. The arts are tough to teach remotely

“But teachers perceive that the arts are the toughest topics to teach remotely: 27 percent say it’s very challenging.

Parent Maggie Hunter, an instructional designer and technical writer in Holmdel, N.J., told EdWeek that she was thrown by an art assignment that asked her son to demonstrate six different shading techniques.

“There was crosshatch, hatching, and ‘scumbling’,” she said. “I have no idea what scumbling is.”

“Unless they participate in or frequently listen to or watch a particular art form, parents may be less familiar with the terminology—even at the elementary level—than they are with, for instance, fractions or syllables. In addition, many arts require specialized materials or equipment (e.g. musical instruments, paint) that families may or may not have at home.

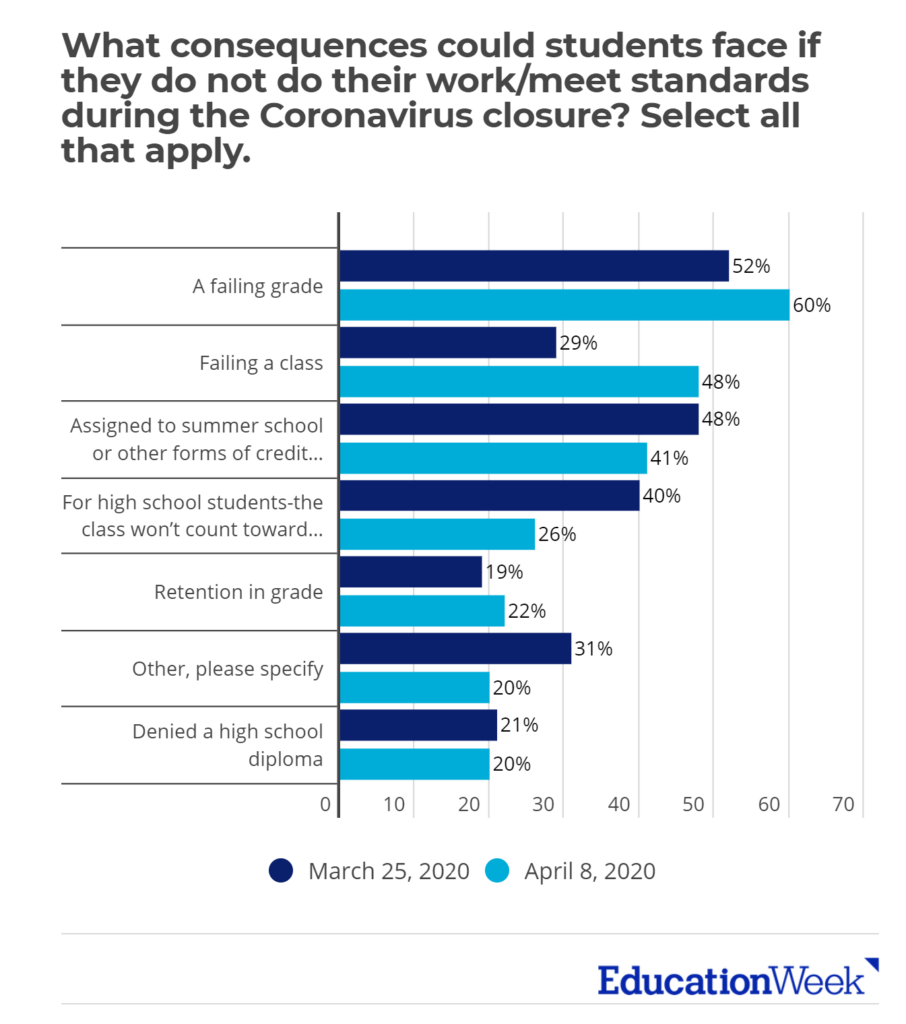

8. More students may face consequences for schoolwork not done during closures

“Since late March, more teachers are reporting that they are partially or fully counting work assigned during closures toward final grades (57 percent versus 50 percent).

“However, practices vary significantly by grade level. Less than half of elementary teachers (43 percent) have decided to fully or partially count work, compared with 59 percent of middle school teachers and 76 percent of high school teachers.

“A failing grade is the most common consequence (now as in March). The share of leaders who say students who slack off during closures could fail a class has also increased substantially.

“’We realize that if we tell kids today, ‘Hey, your grade can’t be any lower than it is now,’ or if we tell them we’re not going to grade them for the rest of the year, we’re going to have a big chunk of kids check out,’ Curtis Hicks, the assistant superintendent of the Salem City Schools in Virginia, told Education Week.’And that’s not healthy for them for the short run, and it’s not healthy for the long term, if students are underprepared for what comes next.'”