This article projects the potential long-term impacts on children whose schooling was impacted by COVID-19, especially those in underprivileged situations. It warns of further increasing achievement gaps, and the huge future economic and health impacts of the kids at stake. I believe it is extremely important to take special consideration of underprivileged communities when approaching this problem because they are the ones most drastically impacted. How will a young child learn if both of their parents (or a single mom/dad) has to go to work in order to put food on the table, and what impact does this have on their future chances of breaking out of the poverty cycle?

—

Dorn, Emma, et al. “COVID-19 and Student Learning in the United States: The Hurt Could Last a Lifetime.” McKinsey & Company, 1 June 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime#.

“The US education system was not built to deal with extended shutdowns like those imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Teachers, administrators, and parents have worked hard to keep learning alive; nevertheless, these efforts are not likely to provide the quality of education that’s delivered in the classroom.

“Even more troubling is the context: the persistent achievement disparities across income levels and between white students and students of black and Hispanic heritage. School shutdowns could not only cause disproportionate learning losses for these students—compounding existing gaps—but also lead more of them to drop out. This could have long-term effects on these children’s long-term economic well-being and on the US economy as a whole.

Learning loss and school closures

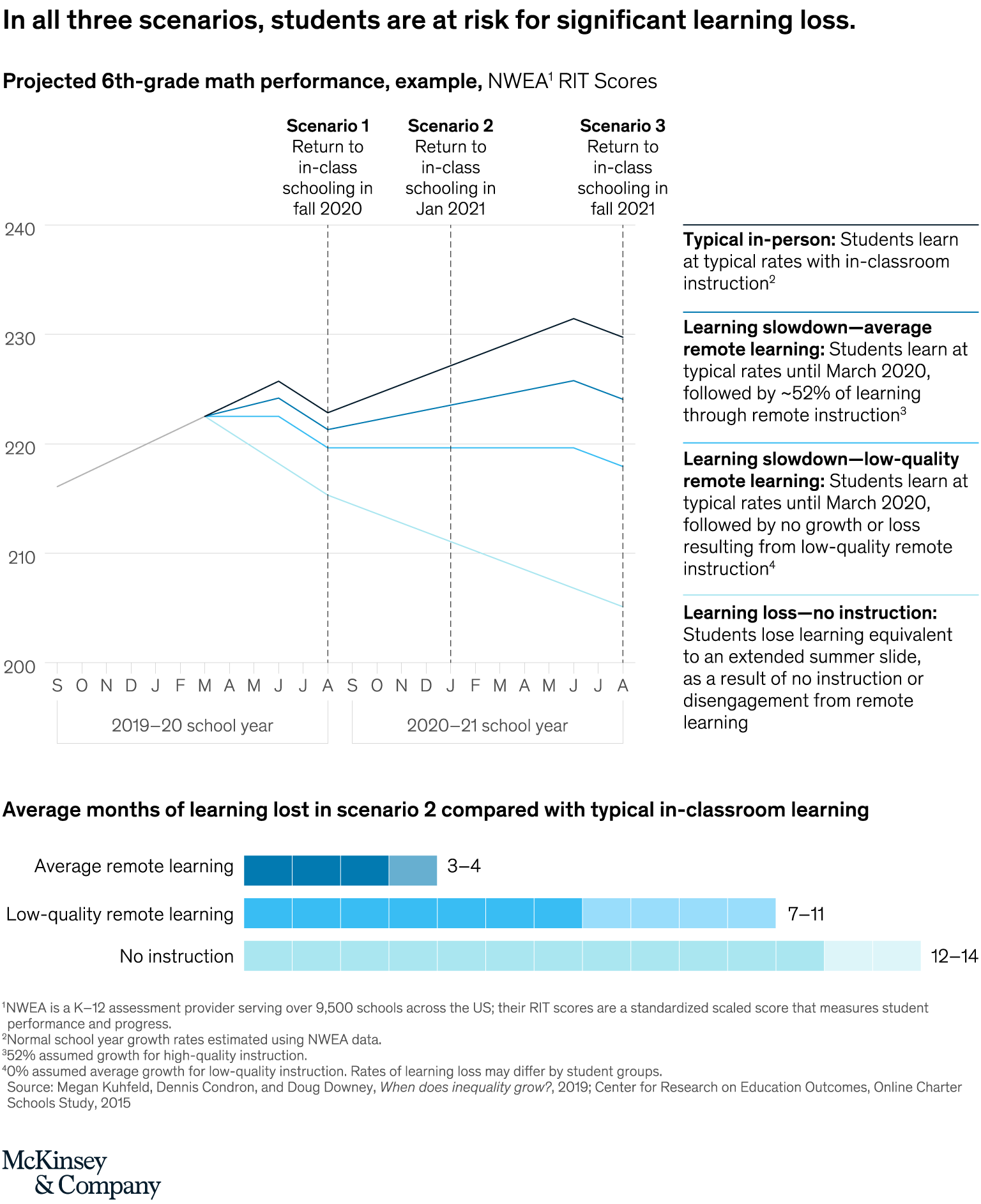

“To that end, we created statistical models to estimate the potential impact of school closures on learning. The models were based on academic studies of the effectiveness of remote learning relative to traditional classroom instruction for three different kinds of students. We then evaluated this information in the context of three different epidemiological scenarios.

“Although students at the best full-time virtual schools can do as well as or better than those at traditional ones, most studies have found that full-time online learning does not deliver the academic results of in-class instruction. Moreover, in 28 states, with around 48 percent of K–12 students, distance learning has not been mandated. As a result, many students may not receive any instruction until schools reopen. Even in places where distance learning is compulsory, significant numbers of students appear to be unaccounted for. In short, the hastily assembled online education currently available is likely to be both less effective, in general, than traditional schooling and to reach fewer students as well.

Likely effects on low-income, black, and Hispanic students

“Learning loss will probably be greatest among low-income, black, and Hispanic students. Lower-income students are less likely to have access to high-quality remote learning or to a conducive learning environment, such as a quiet space with minimal distractions, devices they do not need to share, high-speed internet, and parental academic supervision. Data from Curriculum Associates, creators of the i-Ready digital-instruction and -assessment software, suggest that only 60 percent of low-income students are regularly logging into online instruction; 90 percent of high-income students do. Engagement rates are also lagging behind in schools serving predominantly black and Hispanic students; just 60 to 70 percent are logging in regularly (Exhibit 3).

“These variations translate directly into greater learning loss.The average loss in our middle epidemiological scenario is seven months. But black students may fall behind by 10.3 months, Hispanic students by 9.2 months, and low-income students by more than a year. We estimate that this would exacerbate existing achievement gaps by 15 to 20 percent.

“In addition to learning loss, COVID-19 closures will probably increase high-school drop-out rates. . . The virus is disrupting many of the supports that can help vulnerable kids stay in school: academic engagement and achievement, strong relationships with caring adults, and supportive home environments. In normal circumstances, students who miss more than ten days of school are 36 percent more likely to drop out. In the wake of school closures following natural disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina (2005) and Hurricane Maria (2017), 14 to 20 percent of students never returned to school. We estimate that an additional 2 to 9 percent of high-school students could drop out as a result of the coronavirus and associated school closures—232,000 ninth-to-11th graders (in the mildest scenario) to 1.1 million (in the worst one).

“In addition to the negative effects of learning loss and drop-out rates, other, harder to quantify factors could exacerbate the situation: for example, the crisis is likely to cause social and emotional disruption by increasing social isolation and creating anxiety over the possibility that parents may lose jobs and loved ones could fall ill. Milestones such as graduation ceremonies have been canceled, along with sports and other extracurricular events. These challenges can reduce academic motivation and hurt academic performance and general levels of engagement.

“The loss of learning may also extend beyond the pandemic. Given the economic damage, state budgets are already stressed. Cuts to K–12 education are likely to hit low-income and racial- and ethnic-minority students disproportionately, and that could further widen the achievement gap.

The economic impact of learning loss and dropping out

“These effects—learning loss and higher dropout rates—are not likely to be temporary shocks easily erased in the next academic year. On the contrary, we believe that they may translate into long-term harm for individuals and society.

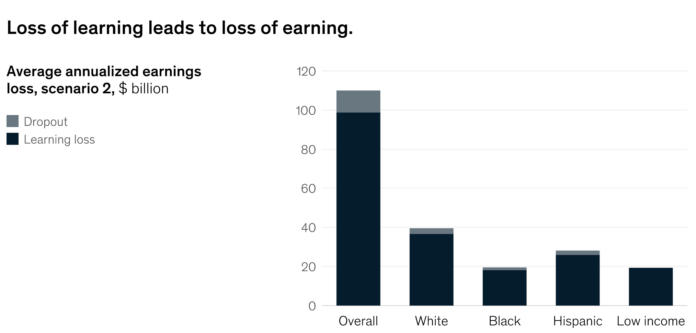

“Using the middle (virus resurgence) epidemiological scenario, in which large-scale in-class instruction does not resume until January 2021, we estimated the economic impact of the learning disruption. (The results would, of course, be worse in the third scenario and better in the first.) All told, we estimate that the average K–12 student in the United States could lose $61,000 to $82,000 in lifetime earnings (in constant 2020 dollars), or the equivalent of a year of full-time work, solely as a result of COVID-19–related learning losses. These costs are significant—and worse for black and Hispanic Americans. While we estimate that white students would earn $1,348 a year less (a 1.6 percent reduction) over a 40-year working life, the figure is $2,186 a year (a 3.3 percent reduction) for black students and $1,809 (3.0 percent) for Hispanic ones.

“This is not just an economic issue. Multiple studies have linked greater educational attainment to improved health, reduced crime and incarceration levels, and increased political participation.

A Call to Action

“If the United States acts quickly and effectively, it may avoid the worst possible outcomes. But if there is a delay or a lack of commitment, COVID-19 could end up worsening existing inequities.

“It is therefore urgent to intervene immediately to support vulnerable students. Many students will continue to take advantage of free learning resources, but school systems must also think creatively about how to encourage ongoing learning over the summer. Initiatives might include expanding existing summer-school programs, working with agencies that run summer camps and youth programs so that they add academics to their activities, and enlisting corporations to identify and train volunteer tutors.

“The necessity of continued remote learning cannot be an excuse for inaction or indifference. There are examples of high-quality online education, and reaching this level should be the general expectation. . . Educators need to use the summer to learn how to make instruction more effective, whatever the scenario.

“Achieving this goal will make it necessary to provide teachers with resources that show them how they can make virtual engagement and instruction effective and to train them in remote-learning best practices. It will also be necessary to work with parents to help create a good learning environment at home, to call upon social and mental health services so that students can cope with the pandemic’s stresses, and to ensure that all students have the infrastructure (such as laptops, tablets, and good broadband) needed for remote learning.

“As a blend of remote and in-classroom learning becomes possible, more flexible staffing models will be required, along with a clear understanding of which activities to prioritize for in-classroom instruction, identification of the students who most need it, and the flexibility to switch between different teaching methods. And all this must be done while school systems keep the most vulnerable students top of mind. That may require investment—something that cannot be taken for granted if state and local government budgets are cut.