Bloomberg CityLab, by Richard Florida on March 22, 2018.

Carl Grodach, Nicole Foster, and James Murdoch conducted research on the relationships between the arts and gentrification, published in Urban Studies. To conduct their research, they used zip codes for 30 large metropolitan centers between the years 2000 and 2013, a period that brought deep gentrification in many places. In the study, multiple aspects of the arts are explored, categorized into fine arts and commercial arts. Fine arts refers to “independent artists, art galleries, fine arts schools, museums, and performing arts companies”, and commercial arts means “film, music, and design industries”.

A significant part of this research is the categorization of zip codes based on level of gentrification, which the team broke into the following categories:

Affluent: “in the top 20% of income areas at the beginning of the study period”

Already gentrified: “follow the same trajectory as “gentrifying” ones, but also have either a median housing value or a median household income in 2013 that was higher than the metro average”

Gentrifying: “experienced an increase in the percentage of over-25-year-olds with a bachelo’rs degree or higher that was equal to or greater than the metro-area increase, as well as an increase in median housing value during the same timeframe”

Potential to gentrify.

No potential to gentrify: “not affluent, but above metro median in terms of both income and housing construction in 2000”

Next the article breaks down some of the stand-out data points from the research. In the year 2000, fine arts and commercial arts were more frequent in areas that were affluent, gentrified, and that had no potential to gentrify. Interestingly enough, areas that had the potential to gentrify or were already gentrifying had fewer art establishments. As for displacement in 2000, the same trend existed. The areas with the lowest amounts of displacement were actually areas deemed to have potential to gentrify.

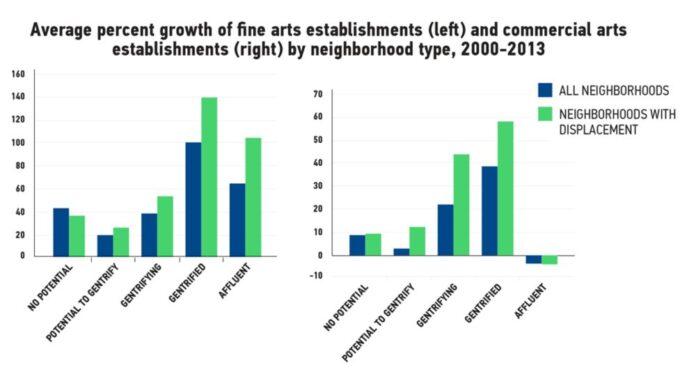

Over a 13 year period; however, the average percentage of growth of fine arts and commercial arts establishments followed a different trend. Already gentrified and affluent neighborhoods showed percent-growth of fine arts establishments ranging from 60%-140% growth. As for commercial arts, growth happened more heavily in gentrifying and already gentrified areas, with a decline in affluent areas. The article supposes that this trend is due to the profit-based nature of commercial arts and their reliance on cheaper rents.

Finally, the article sites specific parts of the research that investigates New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Dallas, to conclude that fine arts and commercial arts establishments are more frequent in affluent or previously gentrified neighborhoods, and least frequent in currently-gentrifying ones. In the research author’s words, “while arts growth does occur in the context of gentrification, an arts presence is not driving the relationship. Rather, gentrified environments lead to arts growth.”

Analysis: I came across this study multiple times in my searches, as it does a comprehensive job looking at the trends between the existence of arts establishments and the gentrification status of the area they’re in. Since the conclusion of the research is that arts growth happens post-gentrification, this article supports my general thesis topic of reclaiming the already-gentrified Short North for BIPOC artists looking to profit off their work and or enjoy other artists’ work.