by: Artspace Editors

One of the most important and wide-ranging paradigm shifts to arise out of the social, political, and aesthetic upheavals of the 20th century is a sustained, visible challenge to the outdated notion of a hard and fast gender binary. As usual, artists have been at the forefront of these changes, creating works that question the normative assumptions of what our bodies should look like or do while drawing from a variety of perspectives on the subject. These divergent representations are far from a modern development, however—as these excerpts from Phaidon’s Body of Art show, inquiries into the complexities of sex and gender transcend both time and place, making this a vital if sadly under-theorized facet of art history.

*This article will focus on two of the nine featured works.*

The sexual ambivalence of the Sleeping Hermaphroditos is more disquieting today than it would have been to ancient viewers, who knew the history of this son of Hermes and Aphrodite. For Hermaphroditos had rejected the advances of the nymph Salmacis, and she, in her distress, asked Zeus to merge their two bodies into one forever, hence the strange union of voluptuous female curves with male genitalia. The late Hellenistic date for the original work from which this Roman copy was made is based on the theatricality of the work: a first impression of a sensuous female nude, and then a surprise on the other side, rendered in realistic detail. The sculpture was discovered in Rome in 1608 and immediately became part of the Borghese collection. Its intrinsic eroticism was intensified in 1619 when Cardinal Scipione Borghese commissioned Gianlorenzo Bernini to sculpt the tufted mattress on which Hermaphroditos sleeps. The torsion of the figure’s body and the slightly raised left foot suggest an impression of restless dreaming, however, rather than deep sleep; the art historian Kenneth Clark saw this work as the direct inspiration for Velázquez’s decidedly alert Rokeby Venus.

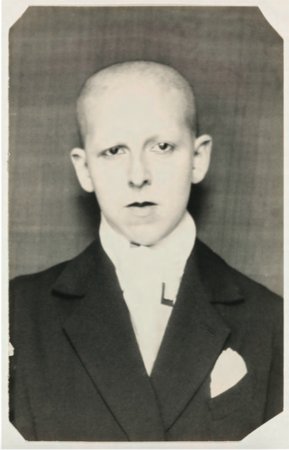

Artistic collaborators, lovers, stepsisters, and French Resistance fighters, Claude Cahun (1854–1954) and Marcel Moore (1892–1972) created works that investigated gender and identity politics in Europe between the wars. Born Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe respectively, the women adopted male pseudonyms. Cahun, who began experimenting with self-portraiture in 1911, is the subject of most of their photographs, which were never exhibited during their lifetimes and only came to light in the 1980s. These performative portraits explore the fluidity of gender. In some Cahun is hyper-feminine in exaggerated make-up and kiss curls, while in others she is hyper-masculine in a sailor suit or with a shaved head (something extremely rare for a woman in the 1920s) and a dandy’s evening finery. Here, Cahun, wearing a cravat and velvet jacket witha pocket-handkerchief looks out at the viewer with a defiant expression. She was interested in upending conventional notions of gender not only in her dress and her art but also her writing. When translating Havelock Ellis’s groundbreaking texts on gender and transgender identity she asserted: “Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neutral is the only gender that always suits me.”

The reason for selecting this article is it highlights how the bending of gender has a long history in the art world. It also highlights its power to shift the viewer’s mind to a subject. “Sleeping Hermaphroditos,” shows that the idea of intersex has been around since ancient times, it also highlights the sexualization of it through the positioning of the subject’s body. The image of Claude Cahun highlights that gender is an easy thing to be manipulated and broken. Both pieces highlight the flexability of gender bianary. The outdoor industry has a real gendering problem and these artworks are a great reminder that it is easily broken.