If creative reuse counts as recycling, people have been doing that for millennia—but early American recycling systems go back to the colonial era, when new materials were hard to come by.

Into the 19th century, as peddlers traveled the countryside to sell manufactured goods, they also purchased recyclable materials from the households they visited, according to Susan Strasser, author of Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash. A 1919 survey in Chicago estimated there were more than 1,800 individual scrap-material dealers.

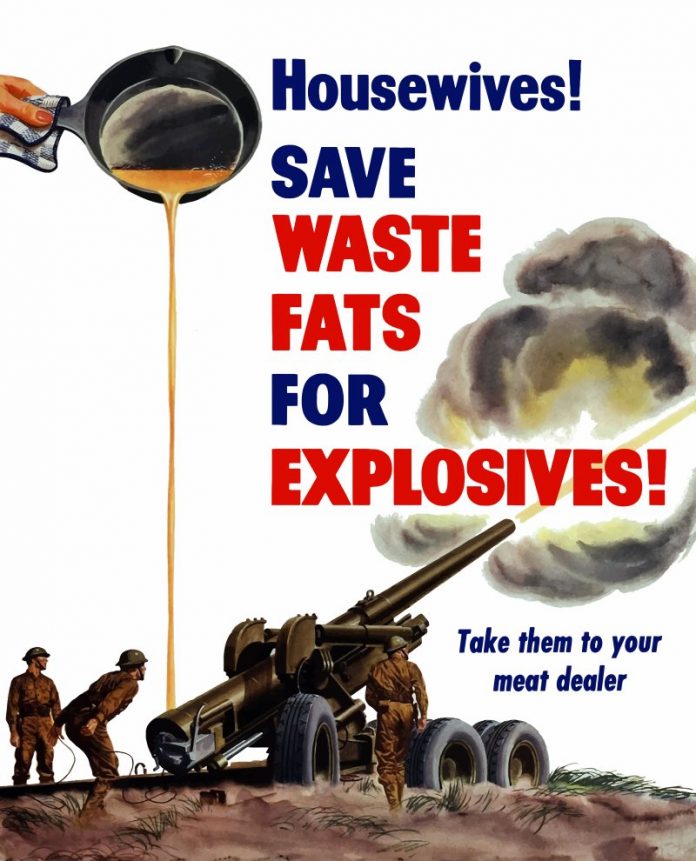

During the Great Depression, the need to reuse continued. Manufacturers marketed products by their dual-use potential. And during World War II, Americans were famously encouraged to collect scrap metal, paper and even cooking waste.

What happened in the 1960s and ’70s wasn’t that recycling was invented, but that the reasons for it changed. Rather than recycle in order to get the most out of the materials, Americans began to recycle in order to deal with the massive amounts of waste produced during the second half of the 20th century. “People start pollution. People can stop it” was the tagline a famous PSA that featured an Italian-American actor as a crying Native-American man.

That ad can be seen as an important moment in the history of recycling, argues Bartow J. Elmore, environmental historian and author of Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism. The companies behind the campaign successfully framed waste as problem for consumers rather than one for the companies that manufactured the items being wasted, he says, and thus framed recycling as something that taxpayers should pay for.

The shift in the framing of recycling can also be seen in bottle-return deposits, says Elmore. In the first half of the 20th century, they were widespread and consumers saw getting their money back as a normal part of purchasing something in a bottle. “Back in the early period, containers are doing 20 trips back and forth between bottler and consumer, largely because people wanted to get their deposit back.”

That system faded away over time, replaced by the idea that consumers should recycle for altruistic reasons, with the fate of the Earth in mind. “I think history shows us why it didn’t work,” he says. “Listen to industry itself in the early 20th century: If you do not put a price on packaging waste, then that stuff is going to be wasted, and it won’t come back.”

Analysis:

Looking at the history of recycling proves to be a highly beneficial exercise, as we understand more holistically how our current culture of wastefulness has arisen. The historical angle presents a different narrative than that which we are accustomed to seeing in discussions about recycling; it brings in a sharp reality check about the economic factors which, this piece seems to argue, should be taken into consideration alongside message-based approaches.