Imagine a small city, built from scratch, overflowing with parks and green space, dense enough to be walkable but not so much to feel crowded. A place where the land is collectively owned, houses are quirkily individualized rather than cookie-cutter, and rents from the land support the creation of luxurious public spaces—like a farmers market housed in a crystal palace, with waterfalls throughout. Rent is low, jobs pay well, there is little inequality, and there are good public transit networks. This is the sort of place envisaged by the Garden City movement, an ambitious and eccentric school of thought about urban planning that popped up in early 20th century Britain and actually produced several complete cities as well as inspired planners across the world for decades.

What is remarkable about the Garden City movement is that something so odd and utopian could become so successful and have a lasting impact. The Garden City movement, while it too disappeared, still left a lasting legacy in urban planning (traces can be found in New Urbanism). But while physical vestiges of the Garden Cities do remain, many of the values that animated the movement have been lost.

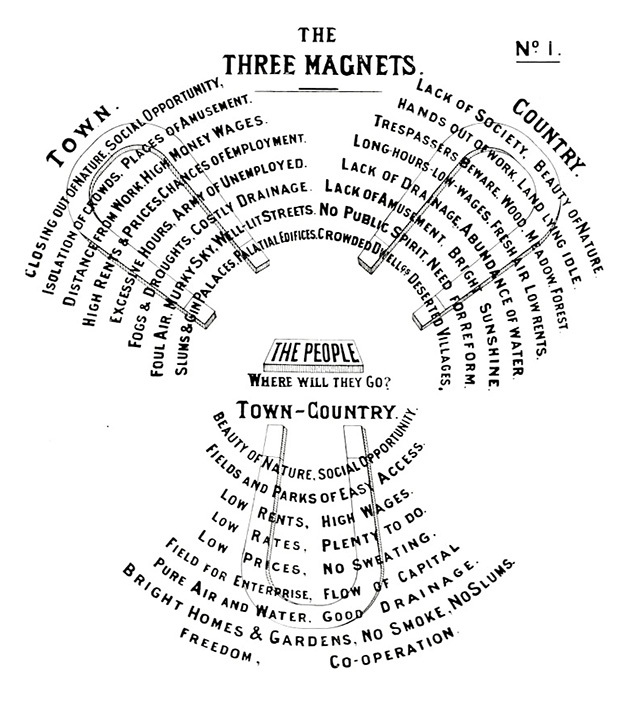

The Garden City movement began in 1898, when British urban planner Ebenezer Howard published To-morrow: A peaceful path to real reform, later republished under the better-known title Garden Cities of To-morrow. Howard’s Garden Cities of To-morrow proposed a new kind of town that would contain the best of both city and country. It would be dense and walkable like a city, but surrounded by natural green belts. It would contain a balance of all that is good in different types of places. He used “three magnets” to show what draws people to towns and the countryside, and what a “town-country” hybrid needed. To sum up: in cities there are higher wages, opportunities, places of amusement, and “palatial edifices,” but there are also high rents, foul air, the isolation of crowds, etc. In the country there is the beauty of nature, but “no public spirit” and low wages. The magnet that would surely draw the most people would combine the advantages of each.

Brett Clark of the University of Oregon describes the model garden city:

At the center of town, covering 5 to 6 acres, a large, well-watered garden was located. The public could enjoy their days in this peaceful social setting. Beginning at the edge of this garden, six wide boulevards radiated out from the center to the circumference of the city, dividing the city into six sections. Larger public buildings, such as city hall, libraries, museums, hospitals, concert halls, and theatres, encircled the garden at the center of town, providing a central point for the public to come together. A large public park was reserved for the space following the public buildings, providing grounds for recreation. Immediately bordering the park, the Crystal Palace, a glass-covered, open-air market and exhibition space, was to be constructed for the trading of manufactured wares and agricultural goods. Moving further outwards, a series of roads in concentric rings provided avenues for several blocks of residential housing. The streets were to be lined with trees and bushes. Each home had ample space for privacy—but not so much that it was a detriment to social interaction—and ample amounts of sunlight and fresh air. Garden space was available at each home for personal enjoyment and the production of food. The architecture and design of the homes were varied, allowing for personal expression and satisfaction, rather than enforcing a lifeless uniformity in structure… The hope was to integrate the homes into the natural setting of the garden city. Surrounding the series of residential rings, a wide Grand Avenue circled the city, providing an additional zone for gardens, schools, and parks. The outer ring of the city consisted of factories, warehouses, dairies, markets, and timber yards. A railroad circled the outskirts of town operating to transport goods between industries and warehouses as well as reducing traffic through the city. Outside of the city, an extensive agricultural belt existed. On this land, small landholdings, allotments, pastures, large farms, forests, orchards, open space for recreation, and charitable institutions existed. No extensions of the city could be developed in the country-side. This agricultural belt had to be maintained for the health of the land and the people.

Planning eventually began to drift from Howard’s original ideas, and abandoned the social aspects of the garden city vision. Katy Lock says that by mid-century “everywhere seemed to be calling itself a garden suburb… They were leafy green places inspired by its art and architecture that… had nothing to do with Howard’s ideas.”Lewis Mumford responded harshly to those who believed suburbs with lots of trees could be “garden cities,” saying that the garden city: “is not a suburb but the antithesis of a suburb: not a rural retreat, but a more integrated foundation for an effective urban life.”

Analysis

The concept of the garden city is about merging the benefits of country living with the benefits of city living. Garden cities are centered around a large garden that is flanked by public buildings such as city hall, libraries, museums, etc. Further outside the center lie the houses, which each have plenty of garden space for personal enjoyment and growing food. Outside the residential rings lie more gardens, schools, and parks. The outside ring of the city is for factories, warehouses, and markets, connected by a railroad. On the very outside of the city lies farms, forests, and orchards. After reading this article I’m not sure that Old Arlington could really be considered a true Garden City. The neighborhood has meandering streets, plenty of small parks, and houses in a variety of architectural styles, but I feel like it might align more with the neighborhoods addressed in the last paragraph- a suburb with lots of green spaces, but a suburb nonetheless. There might be something useful with considering the organization of the Garden City in the planning of a bus route.