Above: Trash bag photographed by me at Buckeye Lake

The beauty of ODNR state parks is that they are free and open to all. However, this makes my job as a designer a little more difficult, where do I start? With such a broad scope of people participating in a diverse range of activities across 76 state parks, there is no one single archetype of visitor. At the most basic level, state park visitors can be divided into two groups, day visitors and overnight visitors. As I was looking into ODNR related current news events, I came across a group of people protesting against fracking proposals in and around state parks. As residents, they feel as though imminent fracking leaks put not only their health, but the health of the environment at risk (Save Ohio Parks 2023). I realized even the most basic categorization of visitors, day vs overnight, didn’t account for a third type of visitor: the local resident. Sure, the local resident visitor probably visits on a daily basis, or even overnight at a camping site, but unlike visitors like me who don’t live in proximity of a state park and therefore can only make infrequent short trips, local residents are fixed. When they leave a state park after their visit, for many, it is only a matter of minutes before they arrive home.

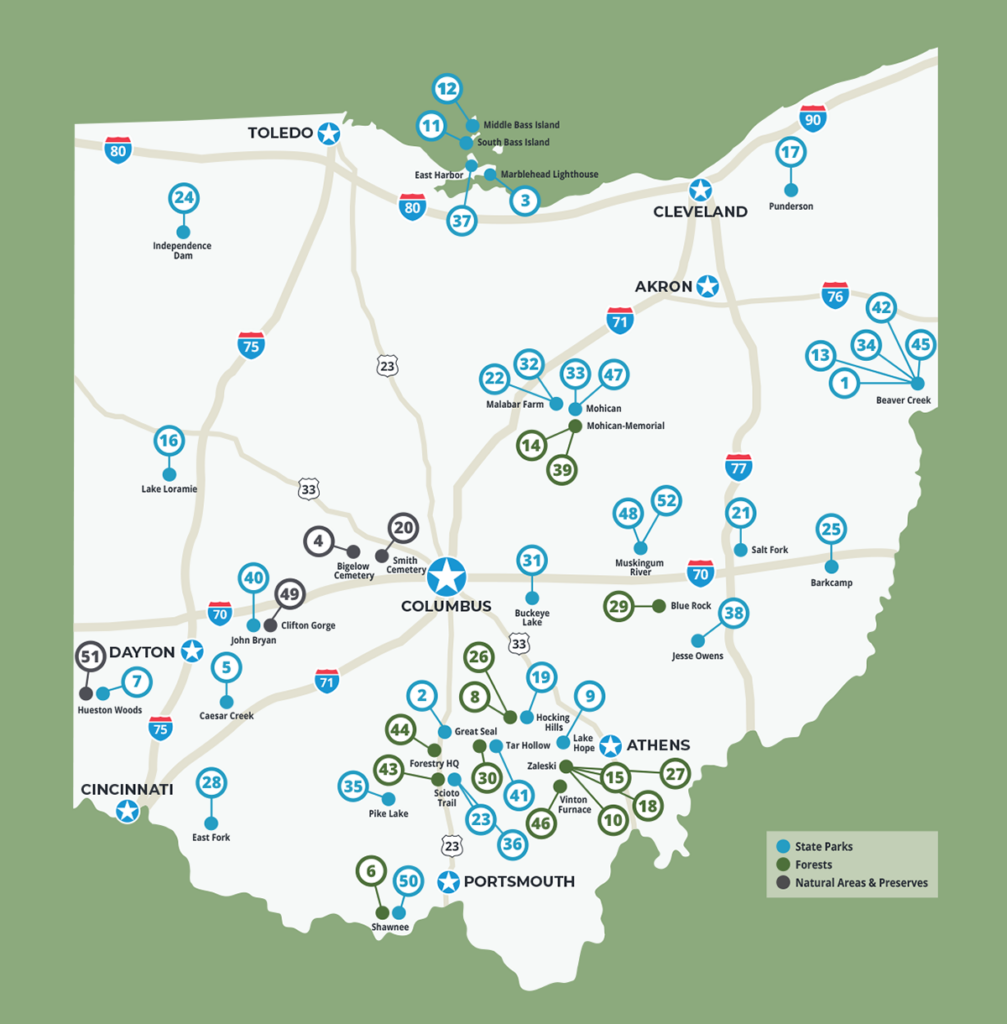

My original focus was local residents of state parks, which is still a very broad scope; there are probably millions of local residents spread out across the 76 state parks. Because so many state parks are located in more rural regions of Ohio, local residents have another thing in common: they are rural Ohioans.

As someone who has always lived in Columbus, and never spent any extended amount of time in rural Ohio, my impression of the region is based on things I’ve heard over the years. Most things I’ve heard are on the negative side, to say the least. At the start of this project I was under the impression that rural Ohio was very conservative, very Christian, and a generally unpleasant population to interact with. I was also aware that this was a very biased perspective, and if I was to understand state park local residents, I would have to confront that bias, which is exactly what I did. My research consists of attempts to understand rural Ohioan’s social, political, economic, and environmental perspectives. I’m a little more familiar with the Appalachian region of Ohio because I’ve studied the region’s history a bit in courses I’ve taken here at OSU. So while I am looking generally at rural Ohioans across Ohio, I am also more specifically looking at rural Ohioans from Appalachia and using the general rural Ohio as a frame of reference because rural culture is entirely new to me.

Who is a Local Resident?

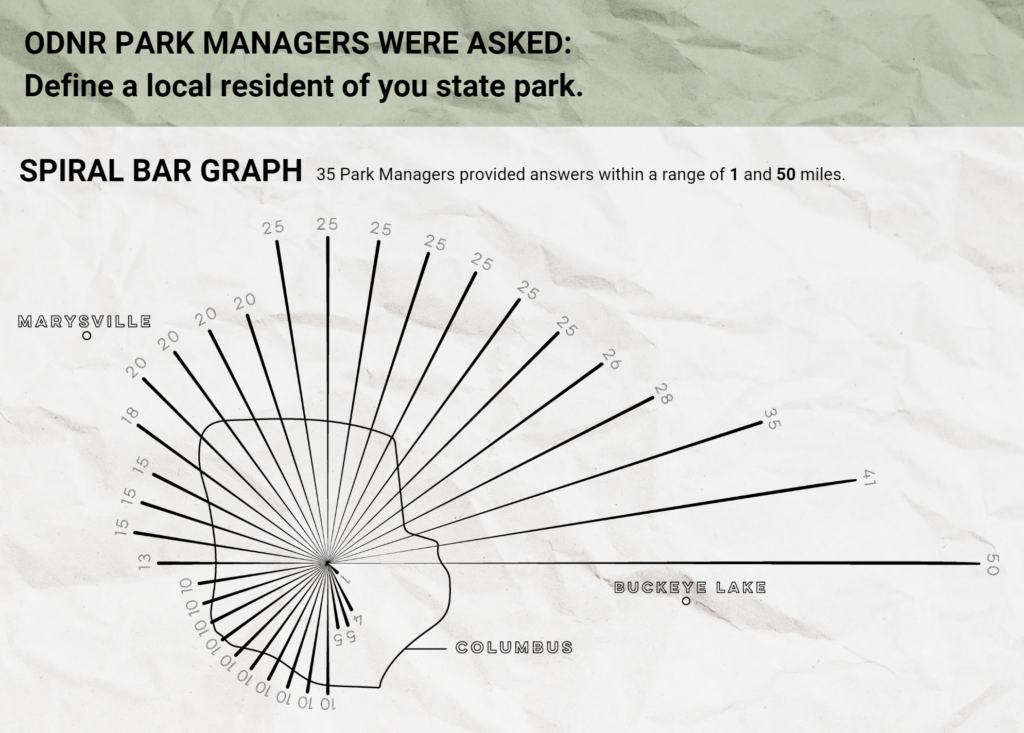

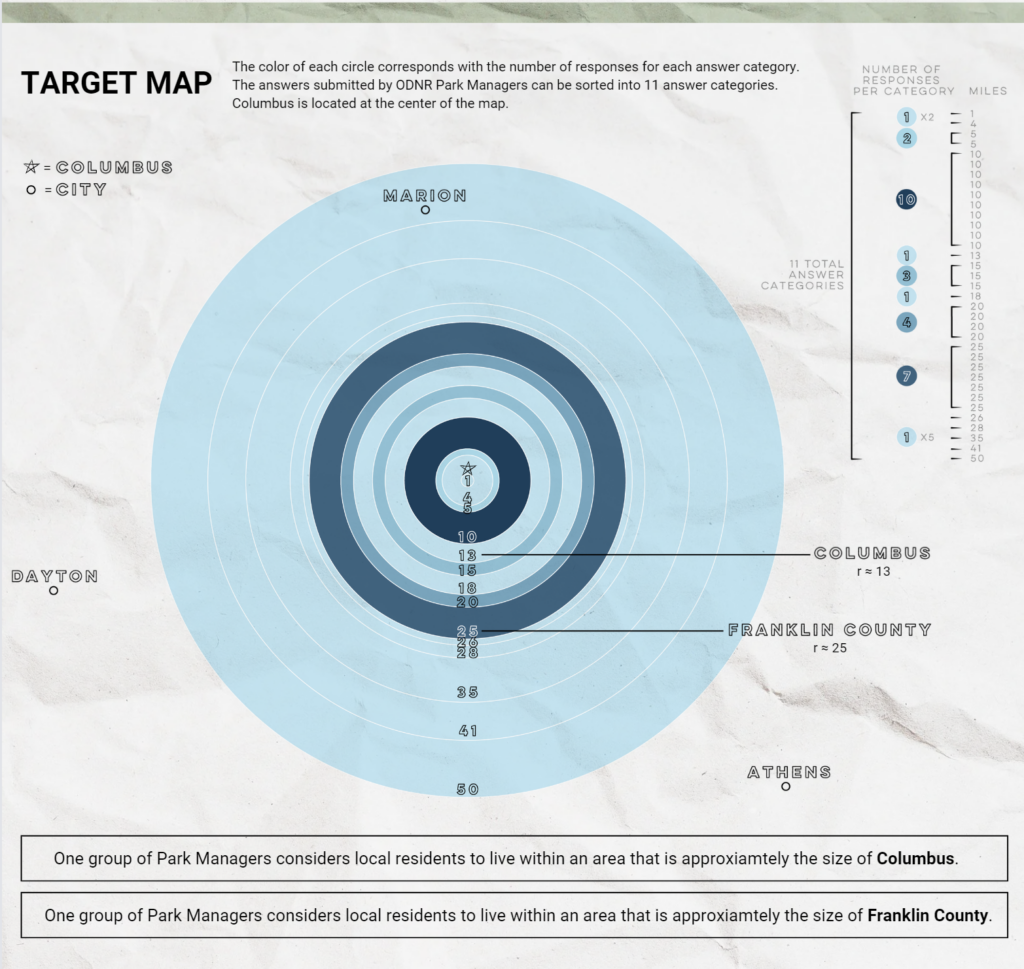

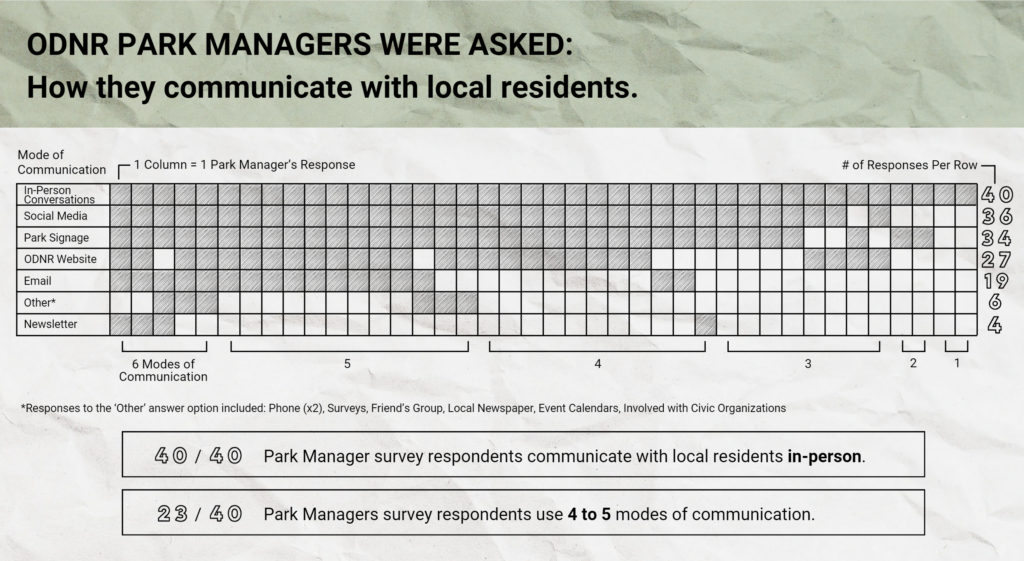

To understand how state park managers perceive this idea of a ‘local resident’, a survey was emailed to 63 out of 76 park managers. When asked to provide a range of miles to define a local resident of a state park, 35 state park managers provided a range of answers between 1 and 50 miles (as seen in the image above).

Local residents were most commonly defined as living within either an area comparable to the size of Columbus, or an area comparable to the size of Franklin County (as seen above).

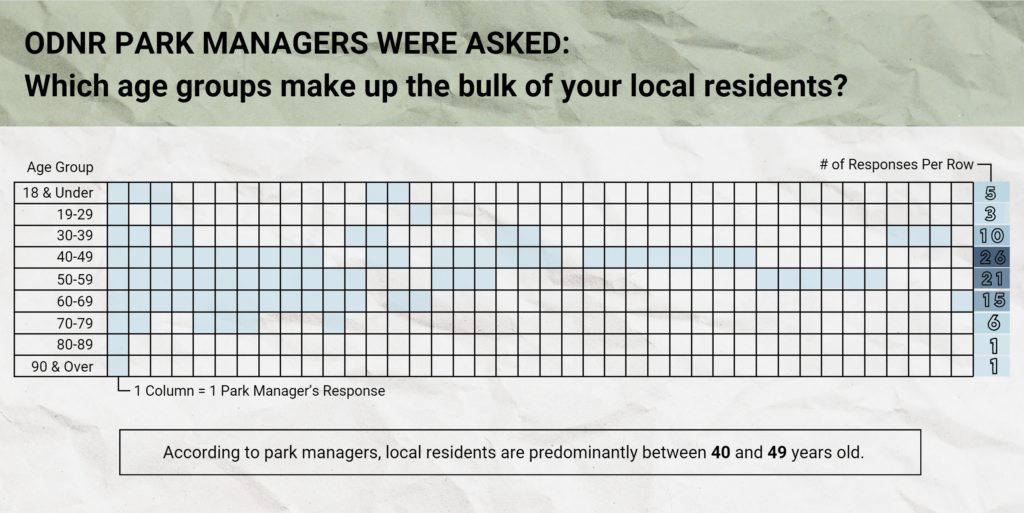

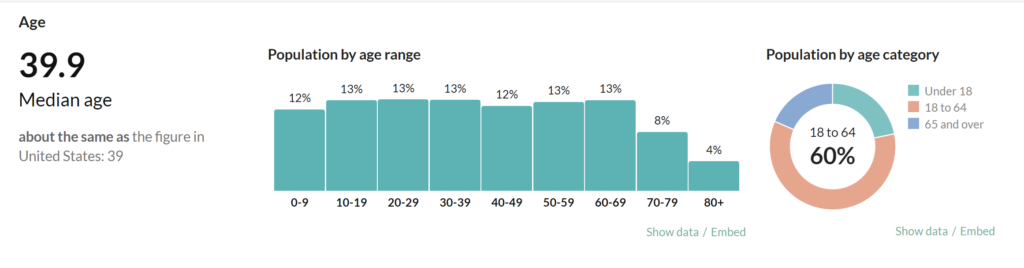

Park managers identified the main age group as 40-49 year olds. It’s worth noting that the 40-49 age group is not the predominant age group of Ohio.

As I continue to research local residents of state parks, I will need to account for the size of the area I look at, and the ages of the people I research.

Political Perspectives of Rural Southeastern Ohioans

In an interview with political scientist and professor in the WGSS department, Cindy Burack, says that while at one time economic liberalism was more salient to sural Ohioans than social conservatism, at this moment, social conservatism is now more influential on rural Ohioans’ political views. This means the generalizations that rural Ohioans are politically and socially conservative are true. However, Cindy also notes that while this may be true at a regional level, at a county or city level, there is more variation.

Economic Perspectives of Rural Southeastern Ohioans

In an interview with ODNR Historical Programs Administrator, Phil Hutchinson, Phil shared his knowledge and background of Southeastern Ohio, also known as a region of Appalachia. A lot of Southeastern Ohioans live in poverty. This is the lasting impact of the coal industry’s exploitation of the region’s natural resources and labor. The area is low-income, there are few jobs nearby, and schools are underfunded.

Social Perspectives of Rural Southeastern Ohioans

When asked about how outsiders are perceived by rural Ohioans, Phil says, “If you come into a community from the outside without any credibility, it kinda gets brushed off as ‘Another outsider coming in who doesn’t know what they’re doing. Some way or another they’re going to exploit us’. In the past 150 years, when people did that, came and made promises about prosperity, they took your coal and leave you with nothing.”

Along the same lines, Cindy relates the social culture to the current political climate and says, “Politics have become one side saying ‘we should do our best to figure out what to do to make our world better,’ and the other side saying, ‘don’t listen to them, they’re making stuff up’. With interventions, you can’t parachute in and tell people something is bad, that what they’re doing is wrong. Because people will be like ‘who are you to tell us what to do’. You have to downplay the imposition from above.”

Environmental Perspectives of Rural Southeastern Ohioans

Cindy remarks that Appalachians view the environment as powerful and indestructible.

Phil says something similar, that there is generational knowledge of the land that is deep, organic, and complex. Because people have an internal knowledge of their environment through their lived experiences growing up with nature, they are not receptive to the outsider scientific sustainability approach. And while there is love for the land, because of the political, economic, and social history, people will lease their land for gas and oil drilling; the region has long been exploited by outsiders, so when outsiders approach rural Ohioans telling them that their practices are unsustainable and scientifically proven to be so, it is seen as another attempt to disown residents of their land.

This means…

While the political, social, and economic perspectives confirm existing stereotypes, the environmental perspectives shift the entire story. Rural Ohioans are not necessarily resistant to sustainability initiatives simply on a difference in opinion, they are resisting in order to protect. The opportunity here is that rural southeastern Ohioans want to protect their environment just as much as we do. The design work begins with understanding how to work with the values of southeastern Ohioans without butting heads due to resistance culture. The answer lies in a community strength building approach (Rural Action), reframing sustainability to include generational understanding of the environment, and treating that generational understanding of the land as knowledge of equal intellect of scientific knowledge.

What can design do?

For example, Ibuku is an architectural firm based in Bali that uses local material, designers, engineers, and craftsmen to make incredibly intricate bamboo structures. The bamboo structures are built in coordination with community needs. Ibuku approaches sustainability through local knowledge and community strengthening (Hardy).

Ibuku is also operating under an entirely different culture and social context. How do you create a relationship where you can have constructive conversations about cultural perceptions of sustainability?A little closer to home is Loma, Nebraska, the filming site for 1995 film To Wong Foo Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar, a road trip movie following three drag queens. Because the Loma is a rural community, one might assume that a queer campy film would land poorly among residents, but in reality it is a source of nostalgia and pride. What we can learn from this is that while rural communities often have a resistance culture, they are still capable of being critical participants on outside culture (Benes).

My “Bigfoot on the Runway” conjecture features a runway collection that explores the manufactured side of the Bigfoot and Appalachian identity through trashy and campy imagery balanced with the deeper generational connections Southeastern Ohioans have with nature and folklore. Similar to Ibuku, the collection would be made in coordination with local material and craft, using waste mitigation techniques. Similar to the phenomenon of To Wong Foo in Loma, “Bigfoot on the Runway” would allow for an identity to be expressed beyond what is generally expected based on political, social, and economic values. Redirecting sustainability away from the tense political, social, and economic atmosphere, and instead integrating through art and playful expression of identity creates a new space where environmental issues such as waste and litter can be thoughtfully examined.

Another thing about resistance culture is that signage doesn’t work. Perhaps this is why in survey responses, 34 out of 40 park managers say one method they use to communicate with local residents is signage, but only 1 park manager prefers signage as a main method of communication, and 23 out of 40 managers prefer in-person conversations.

Cindy explains that in the West Virginia Appalachian region, while there are plenty of signs saying dumping is illegal and will result in fines, it is common for people to ‘dispose’ of large appliances by dumping them cliffside. Because nature is dense and fast growing in these regions, litter is out of sight and out of mind.

My conjecture titled, “Make it Orange”, aims to make it impossible to ignore litter by making single use products offensively orange. The ease of throwing things away is a culture that was manufactured by plastic companies in order to sell more plastic (Copley). “Make it Orange” combats this by getting people to look twice at the trash at hand.

While “Bigfoot on the Runway” is an outlandish stretch, it is identity based and therefore an affirmative approach to sustainability. “Make it Orange” is a solution that operates directly at the trash level, but is also an aggressive approach that might land poorly amongst communities with resistance culture.

In Conclusion

I now have a more nuanced understanding of the values and beliefs of rural Ohioans/Appalachian Ohioans. At the same time, I have had very little interaction with the region and its people. I have a higher level, theoretical knowledge of the Appalachian identity, but next is understanding the community at a ground level as Phil and Cindy suggested. It is then that I can begin to answer the question, how can waste mitigation strategies strengthen rural communities?

About Us. (n.d.). Rural Action. Retrieved September 21, 2024, from https://ruralaction.org/get-to-know-us/about-us/

Benes, R. (2014, March 24). When John Leguizamo Fixed Up My Hometown. Esquire; Esquire. https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/movies/a28046/to-wong-foo-loma-nebraska/

Copley, M. (2024, June 9). Creating a throw-away culture: How companies ingrained plastics in modern life. NPR; NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/06/09/nx-s1-4942415/disposable-plastic-pollution-waste-single-use-recycling-climate-change-fossil-fuels

Hardy, E. (2015). Magical houses, made of bamboo. Ted; TED Talks. https://www.ted.com/talks/elora_hardy_magical_houses_made_of_bamboo?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

Let’s Get Historic: ODNR’s Historic Places Across Ohio. (2021). Ohiodnr.gov. https://ohiodnr.gov/go-and-do/see-the-sights/historic-places/lets-get-historic-sites

Service Area | Foundation for Appalachian Ohio. (2023). Appalachianohio.org. https://appalachianohio.org/about/service-area/

Timeline. (2023, May 14). Save Ohio Parks. https://saveohioparks.org/history/

U.S. Census Bureau (2022). American Community Survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved from Census Reporter Profile page for Ohio <http://censusreporter.org/profiles/04000US39-ohio/>