But let’s start with the QWERTY keyboard. So on most English-language keyboards, the three rows of letter keys are not arranged alphabetically or by frequency of use. Indeed, the two most common letters in English—e and t—aren’t even on the so-called home keys where your fingers rest while typing. You’ve got to reach for them up on the top row, where the letters, from left to right, begin Q W E R T Y. The reasons for this involve typewriter mechanics, a militant vegetarian, and a Wisconsin politician who belonged to three different political parties in the space of eight years.

I love a straightforward story of inventors and their inventions. In fact, in fifth grade, I wrote my first-ever work of nonfiction on the life of Thomas Edison. It begins, “Thomas Alva Edison was a very interesting person who created many interesting inventions, like the light bulb and the very interesting motion picture camera.” I liked the word interesting because my biography had to be written by hand in cursive, and it had to be five pages long, and in my shaky penmanship, “interesting” took up an entire line on its own. Of course, among the interesting things about Edison is that he did not invent either the light bulb or the motion picture camera. In both cases, Edison worked with collaborators to build upon existing inventions, which is I think the central thing that humans are good at. Like, even though fifth grade me loved a story of a rugged individual who invents a light bulb from thin air via the sweat of his brow, the truth is that what makes us special is our capacity for collaboration and accumulation of knowledge. But who wants to hear a story about slow progress through iterative change over decades? Well, you, hopefully.

The earliest typewriters were produced in the 18th century, but they were too slow and too expensive to be mass produced. Over time the expansion of the Industrial Revolution meant that more precision metal parts could be created at lower costs, and by the 1860s, a newspaper publisher and politician in Wisconsin, Christopher Latham Sholes, was trying to create a machine that could print page numbers onto books when he started to think a similar machine could type letters as well.

Sholes was a longtime veteran of Wisconsin politics—he’d served as a Democrat in the Wisconsin state senate before joining the Free Soil Party, which sought to end legal discrimination against African Americans and to prevent the expansion of slavery in the U.S. Sholes later became a Republican and on the political side is most remembered today as a vocal opponent of capital punishment. He led the way toward Wisconsin abolishing the death penalty in 1853. And then there’s his other legacy—the typewriter.

Working with his friends Samuel Soule and Carlos Glidden, Sholes set out to build a typewriter similar to one he’d read about in the magazine Scientific American, which described a “literary piano.” They initially built a typewriter with two rows of keys—literally ebony and ivory, just like a piano—with a mostly alphabetical layout. But because their typewriter was a so-called “blind writer,” which is to say you couldn’t see what you were typing as you typed it, you also couldn’t see when the typewriter had jammed, and the alphabetical layout of the keys led to lots of jams—common letters like S and T were adjacent, and other common letter combinations were also problematic—R was right on top of E in the alphabetical key layout, for instance.

There were many typewriting machines using many different key layouts and design strategies at the time. One of the great challenges of humanity is standardization. Like, learning a new key layout every time you get a new typewriter is wildly inefficient, just as most of us don’t really care if a computer uses USB-A or USB-C; we just want something consistent that works, a cry the world’s tech companies seem unable to hear, but we’re not here to review Apple’s 1-star practice of changing standards every 12 months; we’re here to review the QWERTY keyboard, which blessedly Apple has not yet attempted to abandon.

While designing their typewriter, Sholes and co received help from a wide array of collaborators and advisors, including Thomas Edison. They also found investors, most notably Sholes’ old friend James Densmore. Densmore was a proper eccentric—he was a passionate vegetarian who survived primarily on raw apples, and he was known for getting into arguments with strangers at restaurants who ordered meat dishes. He also cut his pants several inches above the ankle for comfort, and he happened to have a brother, Amos, who studied letter frequency and combinations in English. According to many reports, Amos advised the typewriter manufacturers on how to minimize jams. Meanwhile, stenographers and telegraph operators used prototypes of the machines and provided feedback, leading to more than twenty different iterations of what came to be known as the Sholes and Glidden typewriter. By November of 1868, Sholes had designed a four-row keyboard in which the first row began A E I period question mark. By 1873, the four-row layout began Q W E period T Y. That year, the gun manufacturer Remington and Sons bought the rights to the Sholes and Glidden—with the U.S. Civil War over, they were looking to expand outside of firearms. Engineers at Remington moved the R to the top row of the typewriter, giving us more or less the same key layout we have today.

Analysis

This essay covers the invention of the QWERTY keyboard, the keyboard we all grew up with, learned how to type on, and don’t really give much of a second thought every time we use it. And most of us use it ALL THE TIME. So how did something so crucial to our tech lives come into existence? Through iteration and time. Lots of hands with all sorts of different experience played their part in developing the keyboard layout we know and love today, from a politician to an academic to the town eccentric. Each player had their experience and education to contribute to the development of this keyboard layout, and it was that diversity of thought that allowed that layout to become as widespread as it is today. So here’s my takeaway: When you go to design/engineer/create something. It does NOT stay in your head. You get as many eyes on it as possible to search for unexpected innovations that will make it more useful for all.

One more thing. This article brings up the necessity of standardization. Imagine having to figure out the layout of your keyboard every time you switch products to type. When designing/engineering/creating, one must remember to start broadly, and narrow to personalize only when necessary. When innovating on the banking experience, I shouldn’t be looking at just the ATM outside my apartment. There are lots of other ATM stories to be told, and I need to hear as many as possible to provide the best solution for all.

Source

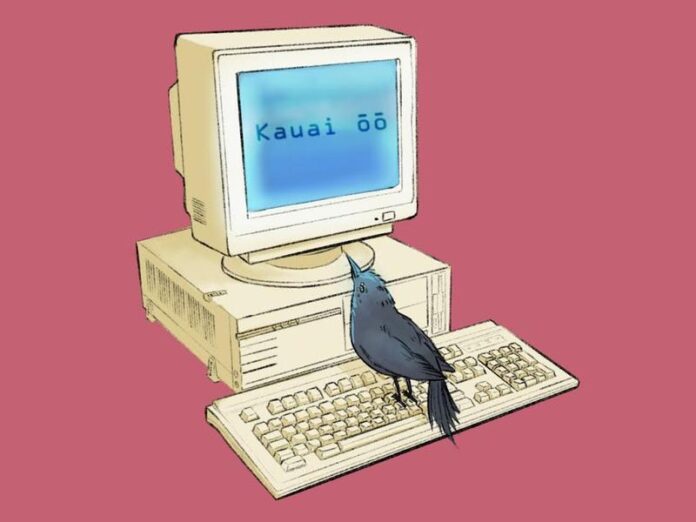

Green, J. (2019, September 26). QWERTY keyboard and the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō: The anthropocene reviewed. WNYC Studios. https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/anthropocene-reviewed/episodes/anthropocene-reviewed-qwerty-keyboard-and-kauai-o-o