Sustainability Education Through Play: Op-Ed

I. The Opposition

I am gearing up to fight one of the most impossible battles against the most impossible opponents. No one knows anything about them: their gender, race, age, or even social class. We don’t know how many of them there are. They could be standing next to you as you read this essay right now. You may have made eye contact with them in the coffee shop the other day. You may even be the enemy yourself.

How do I fight something I know so little about? How do I protect the world from the cumulative actions these opponents take? The more they are left alone, the bigger their impact is and the worse the entire Earth becomes because of it. It’s an important battle, but I continue asking myself, where do I start?

I am talking about littering. Research demonstrates that we do not know who litters. It shows that littering happens across all genders, races, and social classes. Sometimes research findings show age being a factor; the younger ages tend to litter more, but after factoring in the smokers who litter their cigarettes, that threshold becomes insignificant. Research does show that once an area has litter, other people are way more likely to litter there too. That’s the cumulative action I mentioned earlier, the litter just builds on other litter, exaggerating bad habits among people. More trash cans have little impact on litter. More signs only do so much. More fines just do not get enforced enough. What this problem needs is a designer working on a small scale solution in a specific park to spark that engagement in human beings to not litter (Schultz et.al., 2017).

Hi, I’m Erin Shaw and I am a 4th year industrial design major working with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources on finding a step towards a solution to keep the parks litter-free. Using research gathered about education, children’s agency, and sustainability, my design ideas around play could provide an opportunity for children and their families to appreciate the need to protect our environment, specifically in a state park setting.

II. Positive Reinforcement

Just the other day, I went to a play by the Columbus Children’s Theatre called “Fitting In.” The play was geared towards a younger audience of 0-6 year olds and was the majority of the audience members’ first theater production. What stood out to me was the introduction. A crew member came on stage to announce the play, and taught the children what to do during the play. They said to clap when they see something they really like and to laugh when they think something is funny. After practicing both of these actions, the play started. What’s so interesting about laughing and clapping? My reaction was that they were not telling the children what not to do, things like talking, walking around, etc. Rather, they explicitly told the children what they could do: clap and laugh. By giving them things to do during the play, they successfully created a more welcoming atmosphere by explaining what positive interactions the children could engage in during the play. And what did the children do during the show? They clapped and they laughed (Columbus Children’s Theatre, 2024).

III. Sustainability Education

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, sustainability is “the quality of causing little or no damage to the environment and therefore able to continue for a long time” (Cambridge University Press, n.d.). Sustainability is a broad topic with many different facets. It is an important concept to understand so that we can acknowledge our environmental impact and learn ways to mitigate our negative impact. Despite this, sustainability is not part of the academic curriculum in Ohio. The Ohio Department of Education outlines a fair number of learning standards and objectives that need to be met in every school across the state. None of those learning standards explicitly discuss taking care of your environment (Ohio’s Learning Standards, 2024). So let’s create a nature classroom and subjects that are dedicated to teaching sustainability and environmental activism. What would that look like? Here’s an example textbook cover of the new “sustainability” subject for a third grade classroom. I styled it off of my old science textbooks.

Maybe fully immersing myself into changing the education system and adding an entire new classroom and curriculum to underfunded schools is not the answer though.

IV. Put it in a Park

During a recent trip to a park in Maine, I was asked by a park ranger, “Are you here for the park or the trolls?” Intrigued by this question, I became even more interested in visiting this particular park. The trolls were made by a sculpture artist named Thomas Dambo. He practices sustainability by building enormous wooden trolls out of found and recycled objects and places them in parks around the world. By developing the various trolls’ personalities and even providing a scavenger hunt on his website to explore and discover locations of trolls, he’s made going into parks and admiring objects that were once trash, fun (Dambo, n.d.).

.

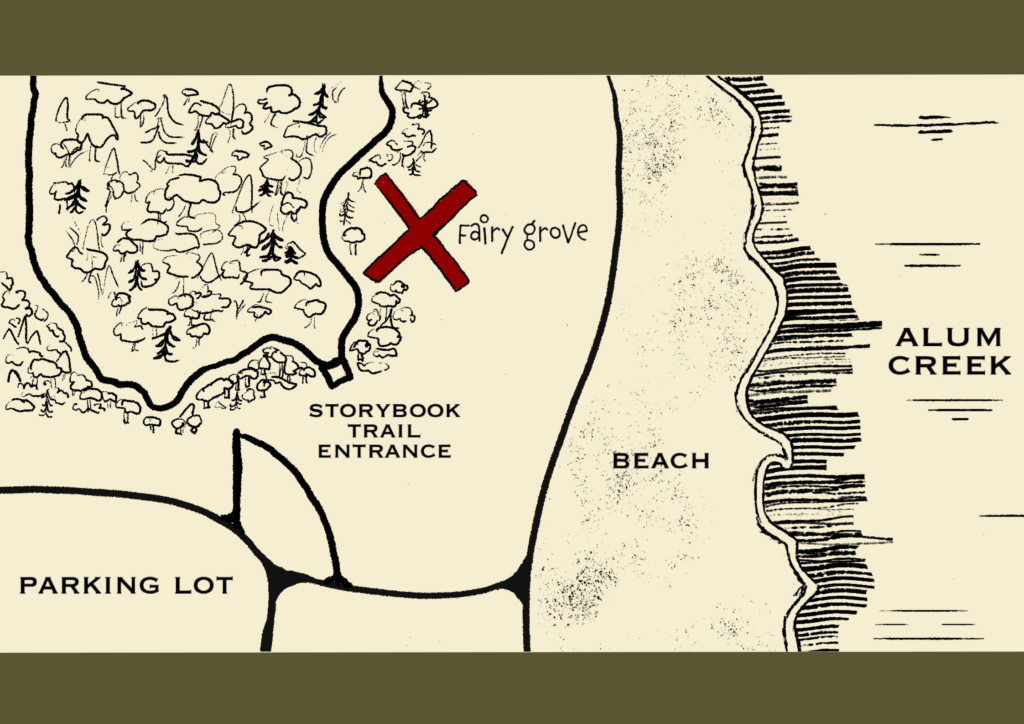

Taking inspiration from the fantasy story building and secret oases of Thomas Dambo’s work, I propose a fairy grove to be built in Alum Creek, Ohio, engaging visitors of all ages to use found objects like bark, sticks, and moss to create homes for the fairies to live in. This could be the start to hundreds more fairy groves in Ohio parks, and could encourage more visitors to the parks who might be asked, “Are you here for the park or the fairies?” Looking for the fairy groves and adding their own elements to the fairy homes could help visitors connect with nature in an interactive way and can incentivize them to keep the fairies’ homes free of human trash.

Because park visitors will be using found natural items to build the fairy houses, this may not encourage them to consider their littering habits and likely would not lead to significant behavioral change. They may simply keep the fairy groves clean of trash, but not think about this once they leave the grove.

V. Children’s Ability to Make a Difference

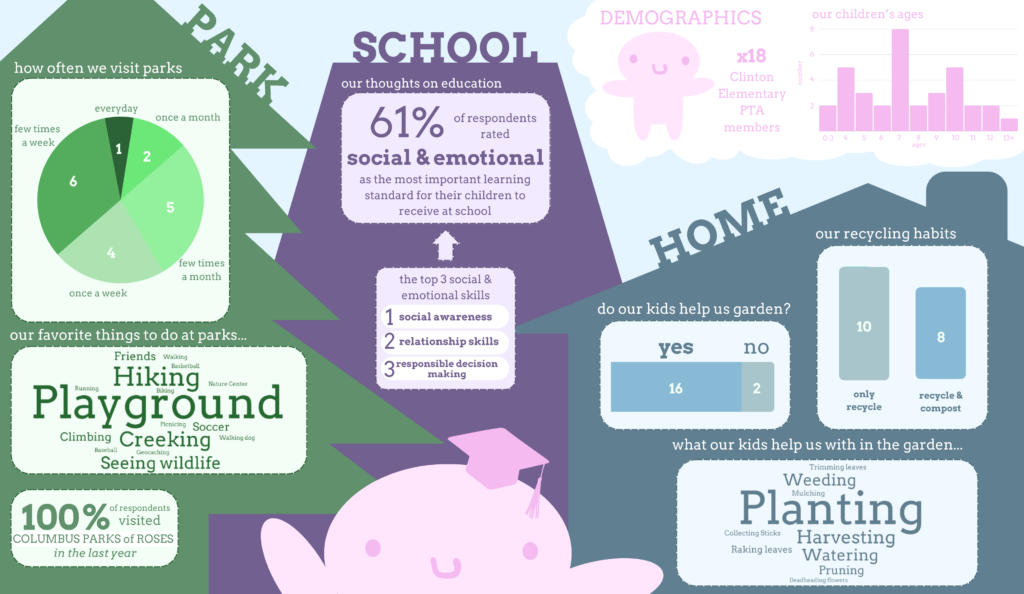

How do I educate people about something as big and complex as environmental impact? One of the first things I thought about in this research process was keeping in mind how smart kids can be. Their imagination is full and their ideas are exciting and unique. My friend Mason created a business at the age of 13 selling brownies to his classmates that has since grown so large that it easily funded his out-of-state college education. Although he was not thinking of the massive scale of his actions at the time, he was still completely capable of taking those first steps towards that achievement (wfaa.com, 2024). I find we sometimes underestimate the abilities of children and their own capabilities of developing connections to larger scale issues. In fact, studies on children’s play demonstrate the positive effect that play items with more affordances have on creativity and cognition. Think of a sandbox and its nearly unlimited play options compared to a single button that may only make the sound of a bird (Zosh et. al., 2017). This path of thinking about play and the interactions, story-telling, and role-playing children are able to learn and do during play, led me to think of one of the most popular areas at a park: the playground. In fact, 88% of primary caregivers interviewed from Clinton Elementary School’s PTA said that playing on the playgrounds was among the top three things their children do at parks (n=18).

VI. The Focus Conjecture

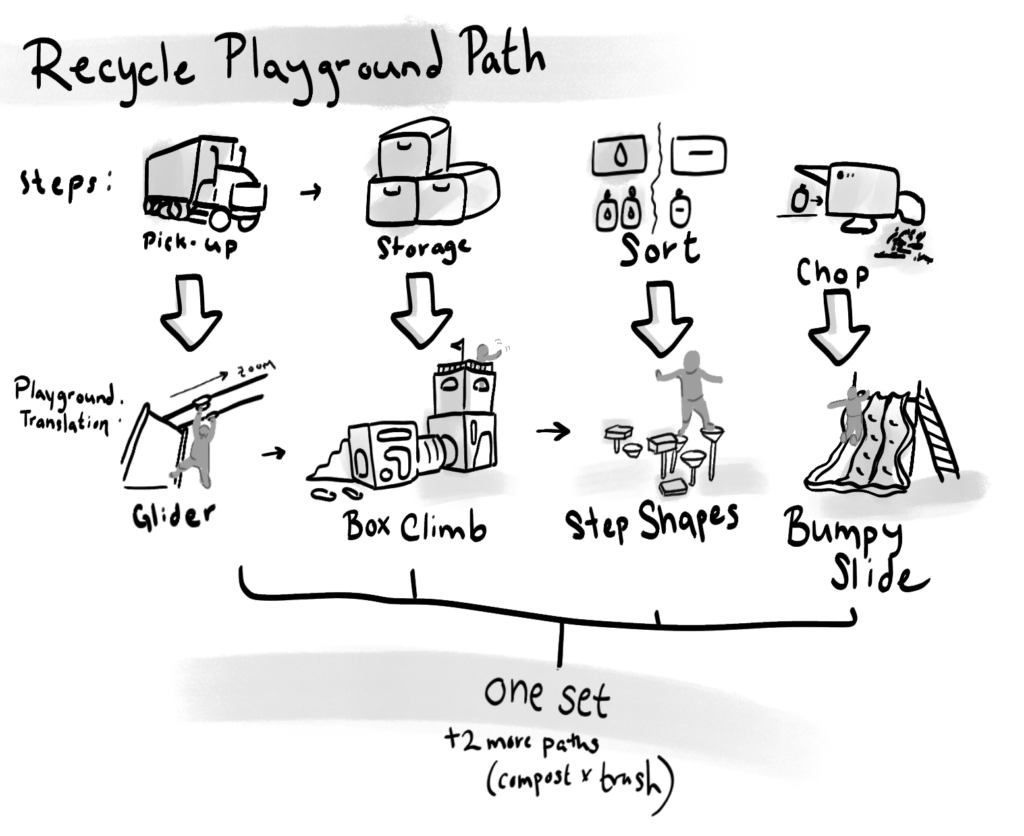

That leads me to the final design conjecture: the sustainability playground. What if we could teach children how recycling, composting and waste management work through the use of a playground? I imagine 3 different paths to take, each one taking you through the process of a piece of waste via the play set. Are you a plastic water bottle? Follow the path to see and learn how plastic bottles are reused into something new. While the full idea is not completely fleshed out, the point stands that through combining play, children’s innate ability to story-tell and role-play, education about sustainability, and proactive measures of telling children what to do rather than what not to do, I can establish a method of teaching the younger audience something as seemingly boring as throwing away a banana peel.

VII. Who Cares?

Why is this important and who is this even affecting? Litter contaminates nature through plastics and chemicals bleeding into the soil. Animals mistake litter for food and can poison themselves or get trapped in packaging. The incorrect disposal of waste can lead the way for bacteria, rodents, and other creatures that can cause diseases in humans to thrive. The presence of litter can predict other social transgressions and increase crime rates in the area. Aesthetically, litter is gross, and it makes an area feel unfriendly, unwelcome, and unclean. It can decrease property values and make people think ill of a location (Schultz et.al, 2013). Just recently, NPR released a podcast discussing the harm that a single Cheeto bag can do to an entire cave ecosystem – think mold and critters. It destroyed the cave system. And that’s just a single bag (Detrow, 2024).

So litter affects you, me, your parents, your neighbors, your pets, your best friends… and I can keep going until I name every person and animal on this Earth. Maybe you are thinking about how it’s the job of janitors and even park managers to clean up the litter. I would counter that by pushing you to think about the myriad of more important things they could be doing instead of cleaning up after people. Think of that neglected corner that makes you sneeze every time you walk by because of the thick layer of dust that always builds up, or how there are never enough paper towels when you make it to the public bathroom. Consider all of the projects and events you wish your park would do to engage with the community more. These things are not impossible to implement, but with the amount of time individuals spend on cleaning up after other people, it’s hard to get to everything and the priorities are forced to change.

VIII. What’s Next?

Think of all the signs you’ve seen saying “please do not litter” or “$500 fine for littering.” This “do not do this” approach to littering is negative and seemingly easy to ignore. Learning from children’s theater, maybe approaching this problem with an active “do this” response can actually ignite change in people. I am focusing on play in a park because children best learn by doing and experiencing their environment through play. When they are engaged in activities rather than just being told about something, they have a stronger chance of internalizing messages they will carry through adulthood. I want to use my design knowledge to influence this engagement by designing sustainability education with play. My hope is that if people can be encouraged to keep our green spaces cleaner, they will generalize this behavior to other settings.

REFERENCES

Cage the elephant – neon pill tour – Friday, August 30, 2024. Riverbend Music Center. (n.d.). https://riverbend.org/concerts/2024/08/cage-the-elephant-neon-pill-tour

Cambridge University Press. (n.d.). Sustainability definition. Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary & Thesaurus. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/sustainability

Columbus Children’s Theatre. (2024, September 4). CCT Sandbox Series. Columbus Children’s Theatre. https://columbuschildrenstheatre.org/shows/

Dambo, T. (n.d.). Hi, I’m Thomas Dambo – recycle artist and activist. Thomasdambo. https://www.thomasdambo.com/

Detrow, S. (2024, September 14). The dire consequences of a bag of Cheetos in a cave. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/09/14/nx-s1-5111577/the-dire-consequences-of-a-bag-of-cheetos-in-a-cave

Hejny, E. M. (2024). The Process of Making a Braided Comic Through Creative Inquiry [Master’s thesis, Ohio State University]. OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1713118950046221

Ohio’s learning standards. Ohio Department of Education. (2024). https://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/OLS-Graphic-Sections/Learning-Standards

Schultz, P. W., Bator, R. J., Large, L. B., Bruni, C. M., & Tabanico, J. J. (2013). Littering in Context: Personal and Environmental Predictors of Littering Behavior. Environment and Behavior, 45(1), 35-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916511412179

wfaa.com. (2024, March 22). Making Da Bomb Brownies. WFAA. https://www.wfaa.com/video/entertainment/television/programs/good-morning-texas/287-0fee6bb7-92fe-4a34-b739-c042b4fd432d

Zosh, J. N., Hopkins, E. J., Jensen, H., Liu, C., Neale, D., Hirsh-Pasek, K., … & Whitebread, D. (2017). Learning through play: a review of the evidence. Billund, Denmark: LEGO Fonden.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My mom for editing my paper and helping me word my thoughts

Professor Will Nickley for his in-depth (and visualized!) critique

Brett Enders for her review and suggestions for improvement on my writing tone

Liz Hejny for her sources and thesis paper on structuring braided narratives which I used to organize my writing better