For all of the horror that emerged from the Second World War, there were some bright spots: With the men out fighting, women were brought into the workplace.

In the mid 1950s, one visionary executive believed women could have a lasting impact on the automobile industry. Harley J. Earl, then the vice president of design at General Motors, introduced “The Damsels of Design,” a group of industrial designers.

“[Earl] really recognized before his contemporaries that women in post-war era really had a lot more buying power, and they were making a lot more decisions about the home, and kind of the car as an extension of the home” says Rebecca Veit, the Designing Women columnist at the magazine Core77.

Veit says that Earl believed that this 10 member design team could give GM “the feminine touch” — a softer aesthetic sensibility that American car consumers could appreciate.

“GM’s PR department really saw a great opportunity to promote the women they were bringing in, and dubbed them ‘The Damsels of Design,’” says Veit. “From everything I’ve read, they really kind of hated the name and being called ‘The Damsels’ — they really felt that it didn’t give them a fair shake as designers.”

Four of “The Damsels” worked as industrial designers for GM-owned Frigidaire, where they helped create the Kitchen of Tomorrow, while the remaining six were tapped specifically for the General Motors Interior-Design Department. Taken together, they’re now considered the first prominent all-female design team in American history.

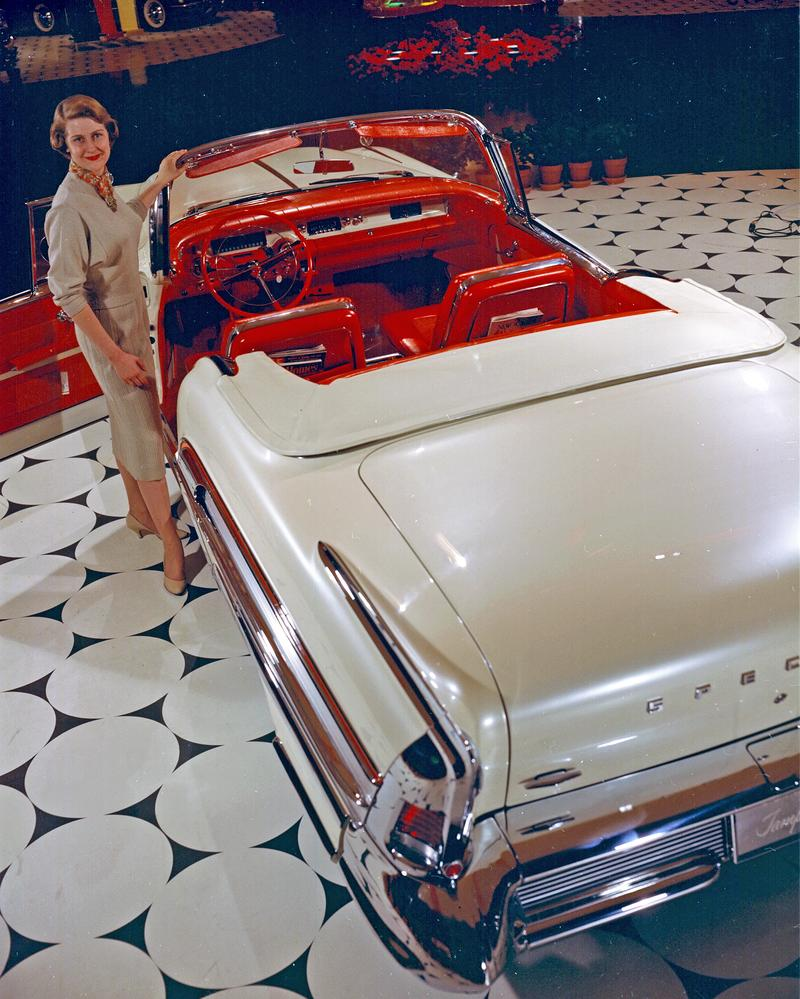

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

…

“One thing that GM specifically did was to promote them with what they called the ‘Feminine Autoshow,’” says Veit. “This was really a time for them to show their taste and design prowess. They designed two to three automobiles each, and really put in some interesting innovations.”

With the Corvette, “The Damsels” introduced the first retractable seat belt, and they also developed other innovations, like glove compartments and light up mirrors — features that would remain in GM cars for decades to come.

“They had fun storage consuls for picnics and for umbrellas, and they also put in some new safety features,” says Veit. “They had some of the first safety latches that could be controlled on the dashboard for children in the back seat.”

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

Veit says that “The Damsels” were thinking more “holistically” about automobiles and the different ways that a car would actually be used in the real world. But “The Damsels” weren’t the only women in the design field at the time.

“There were a lot of women in America, as well as Europe, who were designing and kind of flying under the radar either because they weren’t taken seriously, or because they were working with their husbands and they were kind of in their shadow at the time,” Veit says.

But the story of “The Damsels” didn’t end happily.

“It was kind of a brief blip, unfortunately,” Veit says. “They brought them in around 1955, and in 1958, Harley Earl retired. The man who came after him kind of famously said, ‘No women are going to stand next to my male senior designers.’ So by the early ‘60s, they were gone.”

One of the women — Suzanne Vanderbilt — did stay on at General Motors.

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

…

Vanderbilt never did stop pushing the boundaries forward, even if her company wasn’t responsive. In the 1960s she developed a patent for an inflatable seatback, which allowed for a new approach in automotive back and lumbar support. GM considered her invention, but didn’t actually bring the model into production until decades later.

“I think the women who were referred to as ‘The Damsels of Design’ by GM, they really thought of themselves as designers for men and women,” says Veit. “They didn’t see themselves as designers just for women. I think that kind of design thinking was very forward at the time, and carries over to today — people are designing for people. Female designers today don’t want to be thought of as designing for women. They want to be thought of as designing for everybody.”

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

(Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections)

-Frankman, E., & Raphael, T. J. (2016, April 11). The Damsels of Design: The women who changed automotive history: The takeaway. WNYC Studios. https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/takeaway/segments/gms-all-female-design-team

I loved, loved, loved reading about this design group! Seeing how much beauty and care they put into their car designs just makes me so happy. If I knew about these women before, I might have gone into automotive design. I have never really been into cars that much, but I adore classic cars and wish those designs could make a resurgence. There are a lot of amazing ideas they came up with to make life more joyful for car owners, and I’d love to use them as inspiration for my capstone design. I think the article is correct in dubbing these classic car designs as neither masculine nor feminine but just elegant. The gender neutrality of today’s boxy SUVs is all well and good, but bringing this style and grace back into car design without it costing an arm and a leg is what we should be pushing for. And for Pete’s sake, let’s not go in the hyper-masculine direction of the Cybertruck!