Mass casualties incidents (MCI) such as natural disasters have gone up from costing the United States twenty-nine billion dollars in the 1980s to one-hundred and twenty three billion dollars in 2010s, it is evident that we must prepare for greater disasters in the future. Deaths from natural disasters have increased from 2,870 in the 1980s to 5,224 in the 2010s (Smith 2022). Therefore, we must respond to MCIs in ways that addresses the greater scope and impact of mass casualties. As larger amounts of people are being affected by these mass casualties, the more overwhelming it becomes for first responders.

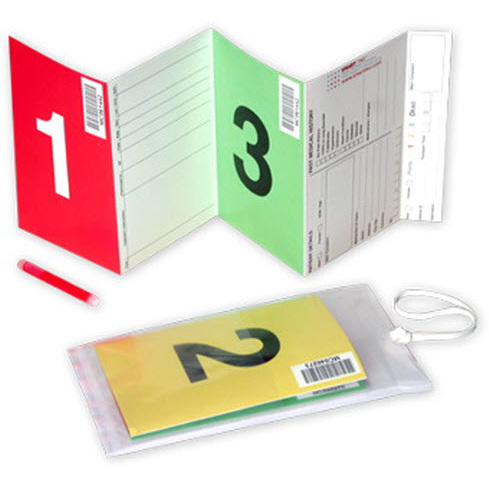

When first responders arrive on the scene, they have to follow triage protocol. Below is an image of the START triage method that some first responders follow. Additionally, below is an image of a triage tag. The triage tag is meant to identify the status of the patient as well as their injuries and other personal information.

The START triage tag not only accounts for the severity of an injury, it also allows for patient tracking and identification.

While a great intervention, it comes with limitations. For example, the tear off tag has little space for information (Lenert et al. 2005). However, with some triage tag designs, it can take up to four minutes long (Brownlee 2014) to fill out the tag. This wastes precious time in responding to other patients who are severely injured. While some tags have improved in efficiency, the paper tag is still poor when it comes to bad weather and motor control skills. The SMART triage tag has helped immensely with patient identification and tracking, however, it is information in a vacuum. It does not add to the “information repository” (Killeen et al. 2006).

Therefore, hospitals and first responders can only access this information if they have the physical paper on hand. In addition, the below MCI process flow chart is what was used at the hospitals during the Las Vegas shooting in 2017. It is evident that patient tracking was one of the main concerns of the healthcare workers. Questions that pop up in the red bubbles concern how to track a patient after a name is erased from the white board, and “how are results matched to the patient?”. What happens when the patient is handed off to the hospital? How can first responders be more efficient and communicative on the field that would help with the hospital response?

Problematic: Responding to an MCI is a traumatic event. It is chaotic, overwhelming, and a logistical nightmare. The last thing first responders want to consider is paperwork. While a mundane task, keeping track of those one has triaged and making sure they arrive and are treated at the hospital is essential to the survival of the casualties and vital to the aftermath of an MCI. Additionally, healthcare workers are responsible for the patients once they arrive at the hospital. Therefore, patient information must be made readily available and communication between the first responders easy and less stressful.

Based on interviews and co-design research sessions conducted with first responders, mainly firefighters and EMTs, it has become apparent that tracking patients is a source of extra stress when triaging patients.

First responders are accountable for the casualties that they triage, and they must keep count of those they treated. Then, they must notify their commander of those numbers, who is then in charge of keeping all that information (El Dorado County Government).

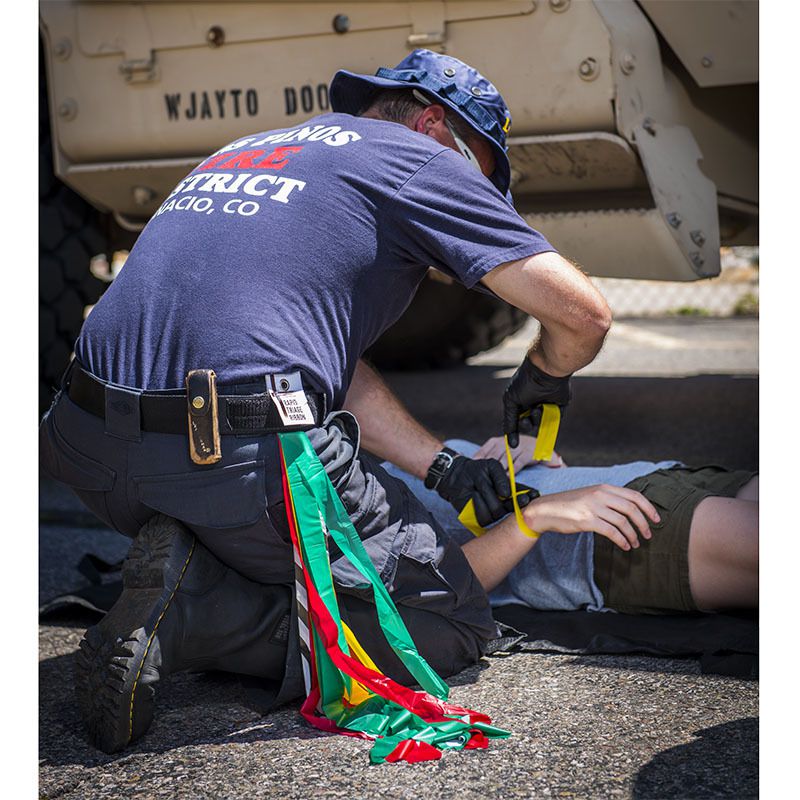

Communication and information is vital for a successful mass casualty response. The Aurora Colorado shooting is an example where information was not disseminated. Triage tags weren’t made available at the beginning. When they were, first responders were not trained on how to use it and it became clear that they were useless. Additionally, before the triage tags were made available on the scene, triage ribbons were used instead (Gale 2021). Motor control skills are a lot more difficult in stressful situations. Therefore, tying on the ribbons is a task in itself. It also only provides information on the physical state someone is in: red, yellow, green, or black. No other information is reported.

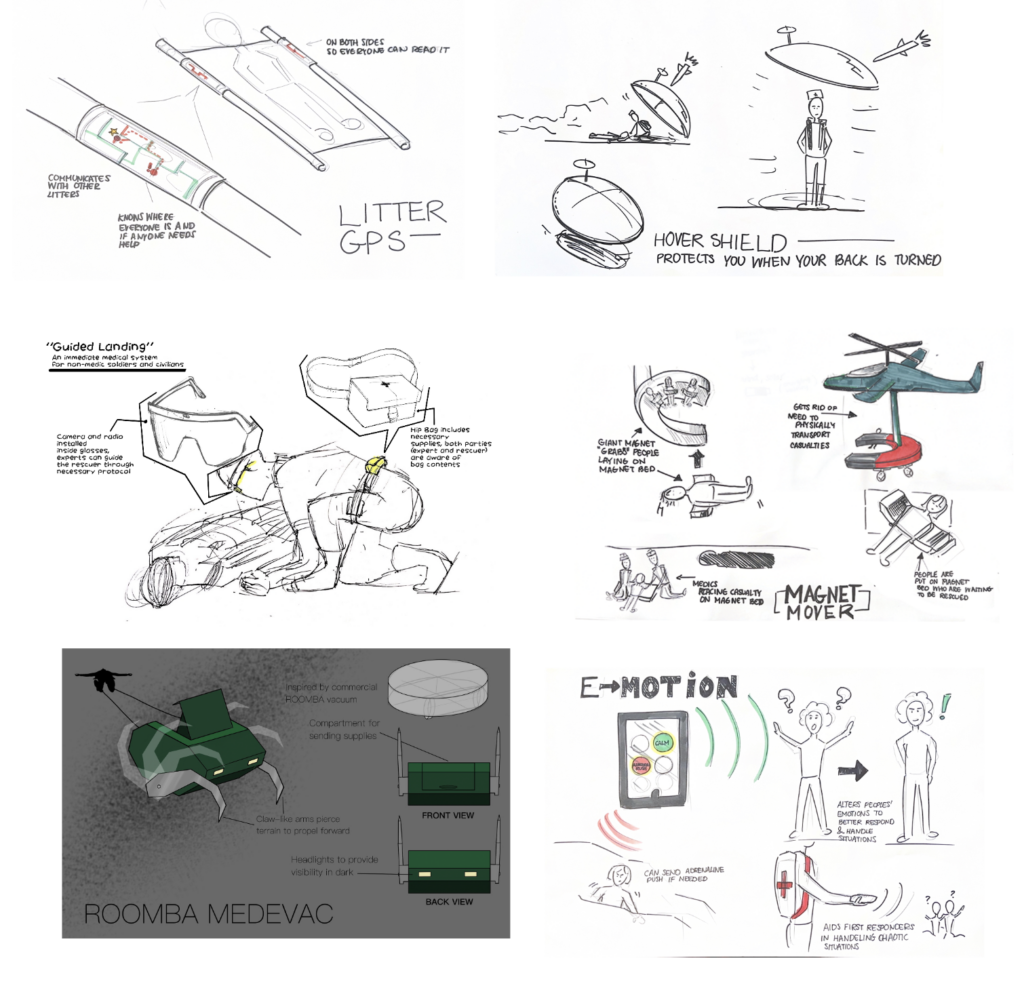

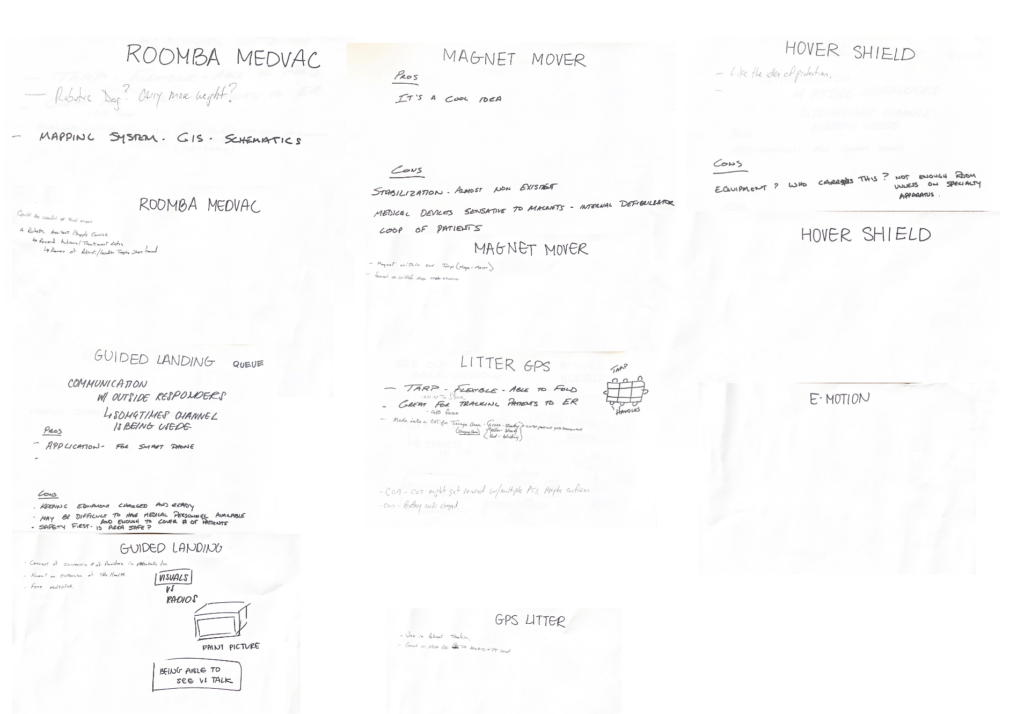

The co-design research sessions brought up interesting insights. I conducted two separate sessions. The first one had five attendees which included the Fire Captain, Research and Development, and other EMS officials. I presented five design conjectures that were related to the topic of mass casualty response and transport. Some ideas were quite wild, such as “The Magnet Mover” which would have a helicopter fly over a mass casualty scene and essentially “pick up” casualties and move them all at once to a safer location. Some less wild ideas included the “GPS Litter” where a GPS device was connected to the litter and notified where everyone was in the MCI scene and communicated location. Another idea was “Guided Landing” where first responders would be able to communicate with civilians on scene through glasses and a radio. After presenting these ideas, I had everyone respond to them. I asked for feedback that included what they did like, what they didn’t like, what could be improved. Afterwards, I handed everyone a bullseye, and small versions of the ideas I presented and had them place them on the bullseye based on how well it captured the problem and what needed improvement. In both sessions, “Guided Landing” and “GPS Litter” landed in the bullseye.

Below are the feedback pages with concrete responses as well as the bullseyes that responded to the design conjectures. Some ideas such as the “Hover Shield” didn’t get responses because they were so out of the ballpark regarding mass casualty response. Throughout our discussion, everyone kept on coming back as to why the GPS litter and Guided Landing were on target. The participants relayed to me that keeping track of patients after they triaged them was stressful. As for the Guided Landing, in both co-design groups, the idea of being able to visually communicate instead of just verbally communicate would make a world of difference to those who are on scene and those who have not yet arrived.

Communication seemed to be a big topic of conversation in both sessions. While I gave ideas that covered transport, protection, and allocation of resources, it was communication that was the main point of focus. This suggested that while physical movement of the casualty is important, communication is what makes everything possible.

During the mass casualty response mock scenario, information dissemination was essential to the success of the transport and survival of the triaged casualties.

The Columbus Fire Department is reverting back to the SALT triage method that also eliminates the SMART triage tag. Instead of using tags to mark patients, EMTs are going to use a triage ribbon to identify patients. This was incredibly interesting. The ribbons were originally used because they were easy and efficient. Even in the mock casualty scenario, I noticed that when a first responder went to use a triage tag, he wasted precious time accessing it and then flipping it over to get to the correct identifier. Additionally, he wrote down no information. A different group that used the ribbons was a lot faster at attending the casualties and getting to everyone on time.

The triage tag became more common because as MCIs became more complex and started including biohazard scenarios, more information about patient status became relevant. However, the more thorough the information the more complex the triage card became until it took a whopping four minutes to fill out. When responding to a scene, first responders must only spend a maximum of thirty seconds on each patient. How can the first responders convey important information such as injury and status while also quickly attending to every casualty on the field? This begs the question of how to be efficient as possible while conveying the most information.

Works cited

Andra M. Farcas , Hashim Q. Zaidi , Nicholas P. Wleklinski & Katie L. Tataris (2022) Implementing a Patient Tracking System in a Large EMS System, Prehospital Emergency Care, 26:2, 305-310, DOI: 10.1080/10903127.2021.1883166

“Aurora Century 16 Theater Shooting After Action Report.” Police Foundation, 2016. https://www.policinginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Aurora-Century-16-Theater-Shooting_AAR.pdf.

Brownlee, John. “A Design History of the Life-Saving Triage Tag.” Fast Company. September 10, 2019. https://www.fastcompany.com/3028492/a-design-history-of-the-life-saving-triage-tag.

El Dorado County Government. “EDC Triage Instructions 2015.” El Dorado County, 2015. https://www.edcgov.us/government/ems/mci/documents/EDC%20TRIAGE%20INSTRUCTIONS%202015.pdf.

Gale, Brendi “The Lost “DOE”: A Quality Improvement Project for Unidentifified Patients” The Elanor Mann School of Nursing. April 2021. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=nursstudent

Killeen, J. P., Chan, T. C., Buono, C., Griswold, W. G., & Lenert, L. A. (2006). A wireless first responder handheld device for rapid triage, patient assessment and documentation during mass casualty incidents. AMIA … Annual Symposium proceedings. AMIA Symposium, 2006, 429–433.

Lenert, L.A., Palmer, D.A., Chan, T.C., and Rao, R. “An Intelligent 802.11 Triage Tag for Medical Response to Disasters.” AMIA … Annual Symposium proceedings. AMIA Symposium, 2005: 440-444.

“1 October After Action Review.” Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, 2019. https://www.lvmpd.com/en-us/Documents/1_October_AAR_Final_06062019.pdf.

“2021 U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Historical.” Climate.gov. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2021-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historical.