Author: David Roberts

Date Published: 26 September 2016

Publisher: Vox

Link: https://www.vox.com/a/new-economy-future/transportation

Since the great interstate-building binge that began in the 1950s, America’s dominant mode of travel hasn’t changed much.

The vehicles have grown more powerful and luxurious. The network of roads, highways, and interstates has grown more elaborate and extensive, and more congested. But the basic elements are the same: It’s people driving cars on roads, with transit, cycling, and walking relegated to the margins.

Today, three technological shifts that could change the transportation system are unfolding in parallel. Let’s review.

1) Autonomous (self-driving) vehicles

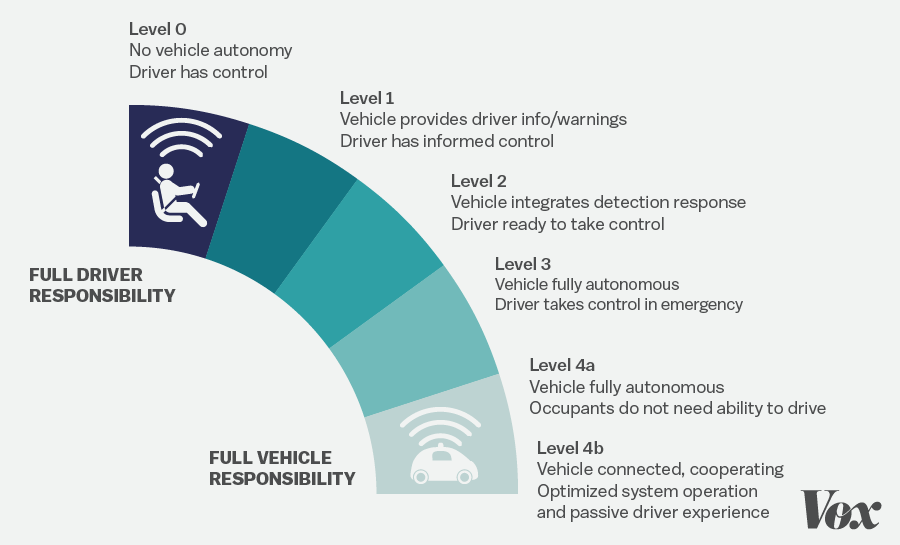

Increasing automation is coming to more and more cars these days. Newer luxury vehicles already stay within lanes, maintain appropriate distance from the car ahead, park themselves, and even valet themselves to you. Cars are marching through the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s levels of automation:

Currently, most new cars have reached level 1, providing the driver with information and warnings; some have reached level 2 in a few specialized contexts, like parking or highway cruising. Soon, level 2 will become more standard and begin bleeding into level 3 (probably via Tesla).

At the same time, several car manufacturers (and companies like Google, Apple, and Uber) are working directly on level 4, 100 percent autonomous vehicles. Such cars already exist — Google has test-driven its versions for more than a million miles on public roads — but they are not quite ready for primetime.

There’s no consensus on exactly when fully autonomous vehicles will be ready for market, but it is definitely predicted to happen at some point.

Just what socioeconomic changes autonomous vehicles might bring about is anyone’s guess. They would destroy thousands of jobs (think of everyone who drives for a living, including truck drivers). But they would also open up mobility to huge classes of people who, due to age, income, or disability, have been unable to get around independently.

2) Vehicle electrification

The US passenger fleet is going to go electric (an argument I have made in several previous posts). Some transit and freight will be electrified, as well. If batteries get substantially better, cheaper, and smaller, and charging infrastructure becomes reliable enough, electrification could even overtake some long-haul or heavy-duty vehicles.

But the electrification of the personal vehicle fleet has already begun. Bloomberg expects fully electric vehicles to reach 35 percent of global new car sales by 2040.

Internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles and electric vehicles are different in ways that current comparisons tend to underplay. I like to quote this passage from a book called Reinventing the Automobile: Personal Urban Mobility for the 21st Century:

A traditional [ICE] car requires elaborate systems of reservoirs, tubes, valves, and pumps to distribute the gasoline, oil, water, air, and exhaust gases, but a battery-electric automobile replaces most of these complicated distribution systems with wires connecting the batteries to the wheels.

That’s all you really need for an EV: batteries, wheels (which contain electric motors), and wires.

Well, technically you need wheels, a battery, a platform for the driver to stand or sit on, and, unless the car is self-driving, some sort of interface to control the vehicle (steering wheel, joystick, touchscreen, what have you). What you build around those simple core components can vary based on the intended use of the vehicle.

Eventually, one could envision most daily travel needs being met by cheap battery-powered vehicles like Segway-style walkers, electric bikes or scooters, or one- or two-person urban pod cars, with long-distance travel reserved for specialized vehicles.

The second development radically expanding the prospects for electric vehicles is the internet and mobile connectivity, which allows the firmware and software controlling electric vehicles (and thus their performance) to continually improve — Tesla is already demonstrating this as well. Eventually, electric cars will be like big mobile iPhones with wheels. The hardware will mostly be boring, except for the improving batteries and charging.

But that’s dreamy future talk. What’s happening now is that electric cars are rapidly coming down the cost curve and competing with ICE vehicles on a total cost of ownership basis in more and more places.

1 + 2) Autonomous electric vehicles

How will these two ongoing technological revolutions mix? What will it look like when all those electric vehicles are also smart, i.e., aware of their surroundings, in wireless communication with other vehicles, and capable of navigating independently?

One possibility it opens up is an end to, or at least a vast reduction in the need for, personal vehicle ownership. Instead, transportation could become almost exclusively a service, as it is now in the case of taxis, Uber/Lyft, and good old-fashioned mass transit.

If you could order up an autonomous electric vehicle (AEV) from a shared fleet with a click of your smartphone — a vehicle appropriately sized to the nature and distance of your trip — you wouldn’t have much incentive to take on the cost and responsibilities of owning a car.

Shared fleets could reduce the total number of vehicles on the road, even if they also increase demand for transportation services.

Also, private vehicles are parked about 95 percent of the time. Shared AEV fleets could ensure that individual vehicles are utilized much more efficiently, which would reduce the need for the parking spaces that eat up an extraordinary amount of valuable urban land. When not in use, AEVs could return to a central charging station/garage to refuel.

Shared AEV fleets could make dense communities more pleasant to live in and easier to build. Plus, smart electric pod vehicles could mix more freely with pedestrians and bikers in some areas, reducing the sharp line between roads and other types of surfaces.

Then again, AEVs could also make suburbia and exurbia more attractive. After all, a long commute isn’t so bad when you can check email and watch cat videos. AEVs could make all private vehicle travel more attractive, possibly increasing the number of vehicles on the road —and sapping what little appetite Americans have for public transit.

3) Distributed energy

More and more energy is being generated by small-scale, distributed energy producers, especially rooftop solar panels and wind turbines.

With the rise of distributed renewable energy has come a commensurate need for energy storage, to even out the variable supply from wind and sunlight, and smart energy management, to balance all the sources and loads on distribution grids.

AEVs can help on both those fronts.

If the grid can communicate with all those millions of AEVs, through “vehicle-to-grid” (V2G) technology, it can coordinate the use of their batteries as a kind of mega battery. When wind and solar are generating more power than the grid needs, the parked and connected fleet can store the excess in their batteries.

Then, when the grid needs power, either to balance out short-term fluctuations in supply or for longer-term coverage, it can draw from those batteries.

AEVs would then be doubly smart, tapped into both the transportation and electricity grids, optimizing the performance of shared AEV fleets to serve both. They would become a kind of vector where the electricity and transportation systems meet, having effects on both that are impossible to predict in advance.

Conclusion

These three revolutions are going to intersect in powerful ways, creating an unstoppable force for change.

Then again, they face an immovable object: the deeply entrenched, path-dependent US transportation system, with all its vested interests, sunk costs, and status quo bias. It’s difficult to change that system at all, much less in any rapid or orderly way.

Something will give; cracks and crevices will open up and expand. We’re unlikely to predict the results in advance, but no matter what, it seems almost certain that the rate of change in the US transportation system over the next 50 years will vastly exceed that of the past 50.

As we know already, the current vehicle scope and market is expected to change drastically over the next 10-20 years. That being said, this article goes into the big expected future trends that are predicted to happen in that time period, as well as mentioning many of the long term effects of these changes. The author addresses the key element of how autonomous vehicle tech is expected to merge with EV tech, and I think that is probably the big takeaway that we need to understand moving forward with this project. Thinking about a backseat space that can both be used as a personally owned space as well as one that could double as a ridesharing space is going to probably be something that we have to do, or should be conversing with Honda about. It can be easy to assume that the future models of these vehicles that they put out may be used in a ridesharing service, similarly to how current models of cars double as Lyfts and Ubers, so it’s important that we consider this moving forward.

Plumer, B., Klein, E., Roberts, D., Matthews, D., Yglesias, M., & Lee, T. B. (2016, September 26). The way we get around is about to change: The new new economy. Vox.com. Retrieved September 26, 2021, from https://www.vox.com/a/new-economy-future/transportation.