Evja is a platform that helps farmers make better decisions using a system based on sensors and predictive algorithms. The startup was born in Naples, Italy, in summer 2015. Their product hit the market last year, starting from Italy, and Evja is already moving forward with partners and customers worldwide.

Paolo says, “We really wanted to use our IoT [Internet of Things] know-how to do something cool in the agricultural market. Agriculture is a key area globally, due to issues such as overpopulation, pollution and deforestation. We thought it would be great if farmers could really understand what was happening on their fields.

…

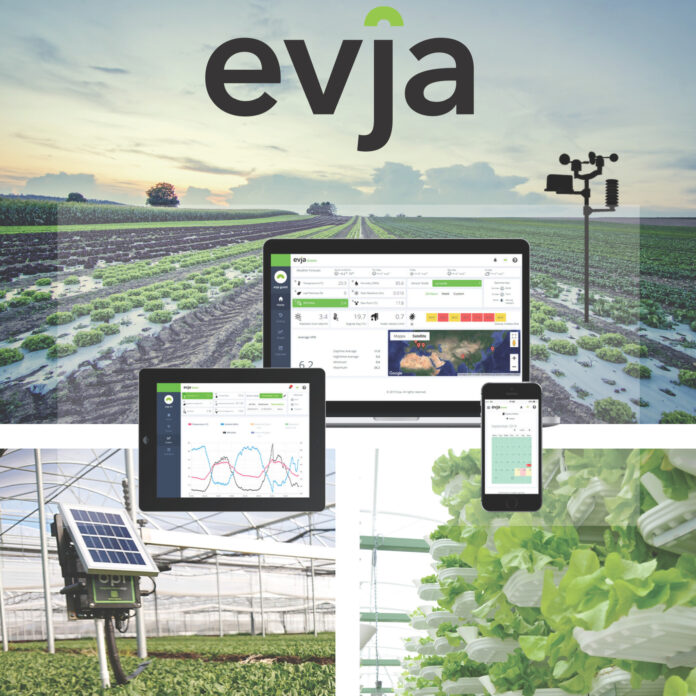

Evja’s founders created OPI, which stands for O.bserve P.revent I.mprove. It is a decision support system (DSS) designed for the agribusiness — a network of sensors collects all significant data from the field and sends them to a central system. All the data is crossed with weather reports and processed through predictive models for pruning, pathogens, and irrigation. The final information is accessible on one’s browser, smartphone, or tablet. With OPI, the firm claims that farmers can save money, time and water, and lower the usage of pesticides for healthier produce. Paolo says, “OPI works like a translator, that makes farmers understand their cultivation. They can forecast adverse weather conditions and prevent plant diseases.”

…

Talking about the objective behind the startup, Paulo says, “We wanted to help advanced, modern farms with high agronomical know-how to further improve their performances, by helping them save time and money and, more importantly, obtain a healthier produce.” On the other hand, they wanted to support farmers with low agronomical know-how, those who have scarce resources and not so advanced tools. For that, they came up with a software that performs like the most advanced ones in the market, and looks like an iPhone app. It gives one an insight into what’s going on and what will happen on the fields, without the need of an expert. “You just fix the box on your plantation and turn it on, and then you can access that area through our website. No installation and no setup required,” Paulo added.

…

The sensors collect the most relevant factors, which vary based on the cultivation, but are usually temperature, humidity, leaf wetness and solar radiation. The farmers can see in real time, on their PC or mobile, the data coming from each one of their fields. So, just with four sensors it can provide advanced information, all readable at a glance. This also means that a single agronomist can manage fields on the other side of the world, and provide remote assistance to the local farmers. The system uses both a mobile connection and the LoRa network, a new technology that allows to cover a very large area with a single antenna. It even works well for farmers with low agronomical knowledge, working in remote areas.

…

The revenue model is based mainly on direct sales and on a double pricing system. The company usually sells OPI as a bundled solution with a one-shot fee, including the hardware and two years of software licence. It also has a renting model that includes hardware and software with a monthly fee starting from €50 per hectare. After starting its sales in the summer of 2017, Evja now serves over a dozen of major companies. Although there are companies using different means of monitoring, such as weather stations, drones or satellites, the Evja team considers them as potential partners, because, Paolo says, “We have developed our software platform to be highly modular. It means we can integrate third-party systems in OPI, and have them work seamlessly for the farmers.”

Source: https://yourstory.com/2018/01/italy-based-agritech-startup-using-iot-help-farmers-know-crops

Evja en

Analysis:

Evja and their software OPI, are an interesting example of leveraging upcoming digital capabilities in the agriculture sector. With their work targeting a specific point of the food supply chain, they may be able to help reduce waste and unnecessary use of materials by empowering farmers with the data to make good decisions.

However, since this business acts as an intervention at a specific part of the food supply chain, I question if and how well they take into account the totality of the food system. For example, do we need to be growing more food? Or is the issue in how that food is distributed? If the answer is the latter, how will implementing this technology affect the environmental consequences pf increased agricultural output?

Despite this, Evja and OPI offer insight into how new technology in the digital world can be applied to the agricultural sector. They illuminate how different physical and virtual components can work together to ensure better yield for farmers.