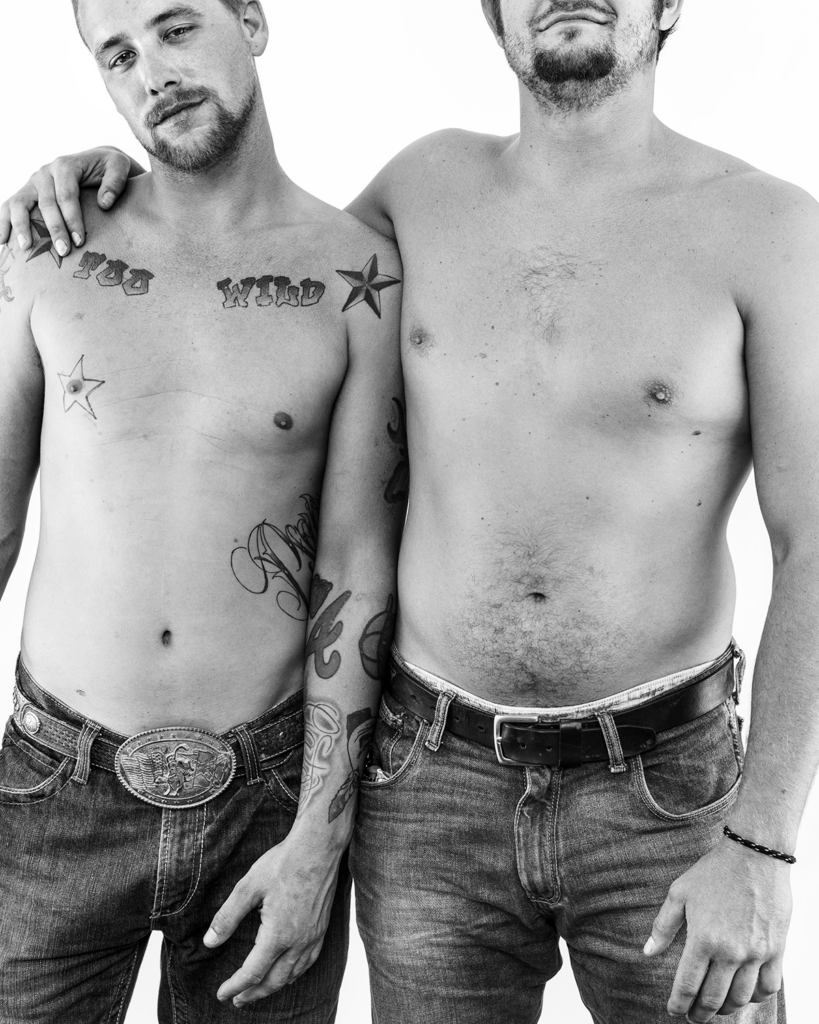

Above: Photos from “Looking at Appalachia” by Roger May

“In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson declared unconditional war on poverty in the United States and nowhere was this war more photographed than Appalachia. A quick Google image search of “war on poverty” will yield several photographs of President Johnson on the porch of the Fletcher family home in Inez, Kentucky.

Many of the War on Poverty photographs, whether intentional or not, became a visual definition of Appalachia. These images have often drawn from the poorest areas and people to gain support for the intended cause, but unjustly came to represent the entirety of the region while simultaneously perpetuating stereotypes.

In an attempt to explore the diversity of Appalachia and establish a visual counter point, this project looks at Appalachia fifty years after the declaration of the War on Poverty. Drawing from a diverse population of photographers within the region, this new crowdsourced image archive will serve as a reference that is defined by its people as opposed to political legislation.” (May 2021)

“In After Photography (2009), Ritchin suggests that the digital photograph acts less as “window” than “mosaic,” not only because any digital image consists of pixels, but because once digital, any image exists as a link within a larger network. Photography in a networked environment “is far from a mechanical recording; it becomes a collaborative, multivocal interrogation of both external and internal realities in which the initial exposure is only a minimalist starting point.” In Looking at Appalachia each photograph speaks to “Appalachia” in its own way, while commenting upon the reality that other images purport. Looking at Appalachia offers a mosaic of disparate images in dialogue with one another. Any image added to the mosaic does not move us closer to completion but only complicates attempts to define a “region.” Because the network is always an open-ended structure, an open call for additional contexts, commentaries, and contributions, the project can never be “finished”—even after the editorial board stops adding images. It is in those gaps and contradictions among a large array that the project succeeds in evoking a sense of Appalachia while offering less and less certainty as to what exactly Appalachia contains.” (Nunes 2017)

I love the vibrancy of these photos, my favorite being the first photo. Pots on the stove are steaming, a salt lamp emits a warm glow, and the golden sunlight makes the photo feel surreal and dreamlike. The space holds life which juxtaposes many more common photos of Appalachia that show crumbling houses that are eerily beautiful in their decay. The former shows an Appalachia that is thriving in the present while the latter portrays Appalachia as a ghost of the past.

When researching artists who photograph Appalachia, I was confused when many stated their goal was to shed new light on the region in order to overcome stereotypes, yet many of their photos, including photos from this collection, still showcase Appalachia in many stereotypical ways. I chose to feature Looking at Appalachia because I saw the most diversity of subject matter, but even in this project there are still many photos of poverty, sunbleached and peeling houses, and christian imagery.

Reading Nunes’ critical analysis of the identity of Appalachia helped me understand that the goal of photographing the region isn’t to make a new Appalachia, or even move on from past descriptions/stereotypes of Appalachia. As I was looking for a photographer to feature in this article, I was trying to find the right images of Appalachia. I couldn’t find that, and I still haven’t, because there is no one right way to define the identity of Appalachia.

I chose this project to feature because the format, a compilation of photos from photographers all across the region both amateur and professional, provided the most complex narrative of Appalachia. Looking at Appalachia makes me want to go to the region and take photos. I’d be bringing the bias of an outsider, but that perspective is still relevant because we should know, what do outsiders see when they find themselves physically confronted by Appalachia? What do outside visitors to Appalachia’s state parks contribute to Appalachia’s identity? How do they complicate it?

May, R. (2021). Looking at Appalachia [Photography]. https://lookingatappalachia.org/

Nunes, M. (2017, November 17). Ways of Unseeing: Crowdsourcing the Frame in Roger May’s Looking at Appalachia. Southern Spaces. https://southernspaces.org/2017/ways-unseeing-crowdsourcing-frame-roger-mays-looking-appalachia/