(FROM THE FILM)

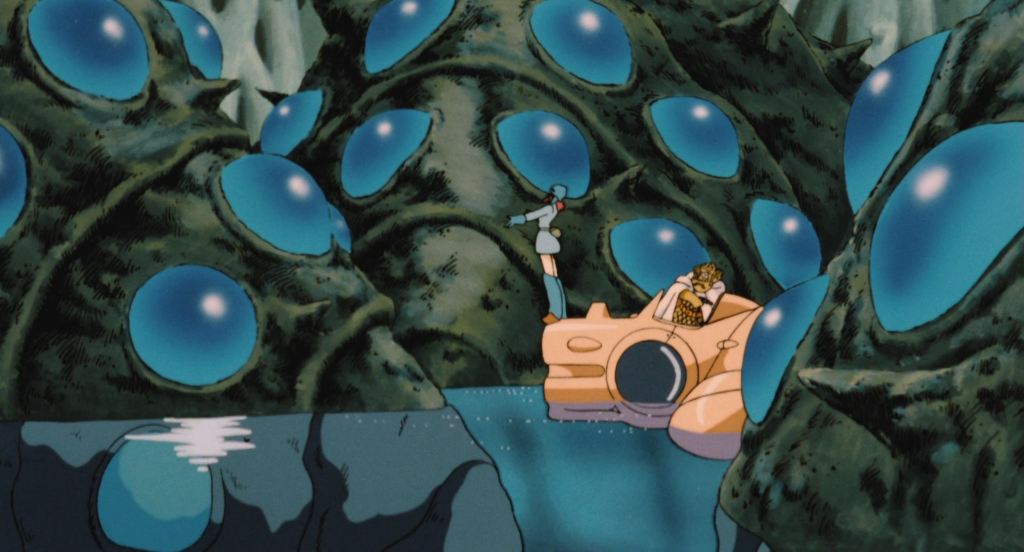

YUPA: “Nausicaa! What are you doing here? This chamber is filled with toxic plants.”

NAUSICAÃ: “I collected the spores and grew them down here myself. Don’t worry the plants aren’t poisonous.”

YUPA: “Not poisonous? Its true, the air is pure in here. But I know these plants from the jungle. These are some of the most lethal.”

NAUSICAÃ: “I irrigated this chamber using water drawn from deep underground by the castle windmill. I used soil drawn from there as well. I found that with clean water and soil, the plants from the toxic jungle aren’t poisonous. All the poison is in the soil. Even the topsoil in our valley is polluted. But…I don’t understand. Who could have polluted the entire earth?” (Miyazaki 2004).

(ON MIYAZAKI)

“During the fourteenth century, the word “pollution” was considered a theological term that signified moral contamination. In traditional Japanese culture, spiritual and physical pollution are closely related. Miyazaki ardently believes that when humans moved from hunting and gathering to living in an agrarian society, they became focused on manipulating their environment for their own personal desires. He stated, “It was in this period that people changed their value system from gods to money.” This shift of values indicated a change in culture concerning our relationship with nature, and Miyazaki wanted to make films about that shift.

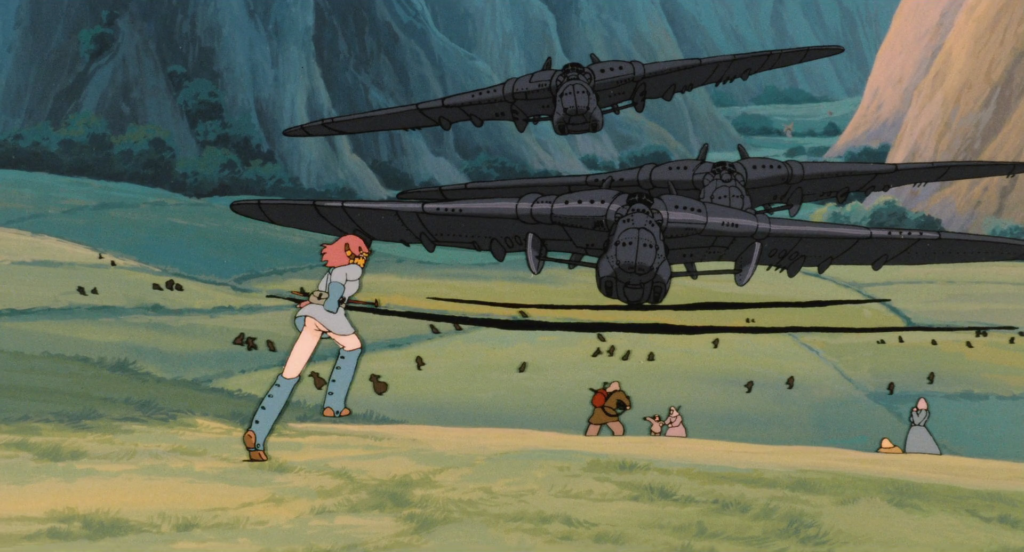

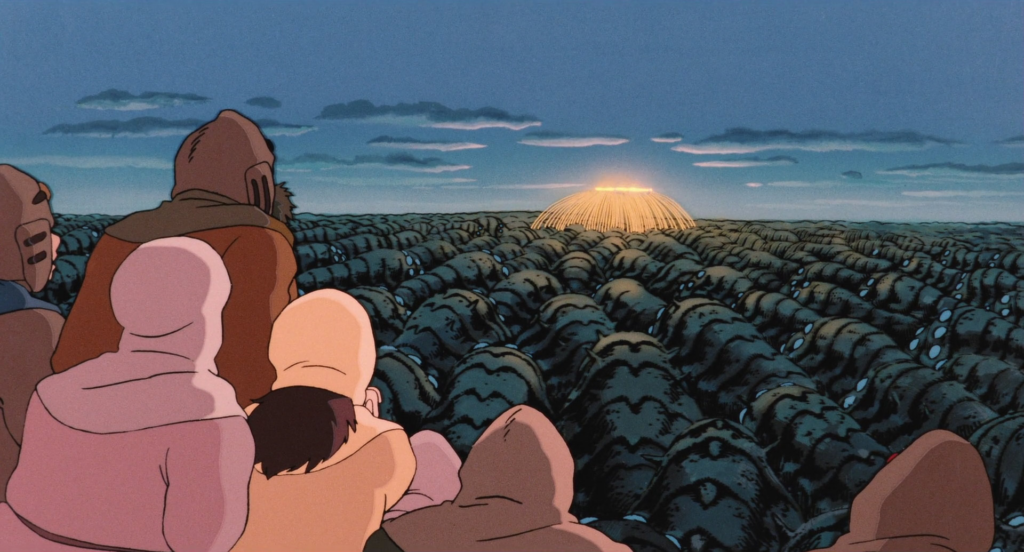

The narrative of Nausicaä examines this disconnect. The apocalyptic environment arose from the Ceramic Wars, a thousand years earlier. The decimation the people suffered pushed them backward to an agrarian and feudal society. Once again, they are making the same choices about how to cope with the environmental problems that could lead to their annihilation. By focusing on the cycle of environmental mistakes that his characters make, he wants the audience to question our choices, bringing awareness to our relationship with nature.” (Gwendolyn 2015).

Despite being 40 years old, the messages in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind are especially relevant today. Nature is valued as a resource to be taken from and hardly, if ever, given anything in exchange. Miyazaki doesn’t just define relationships between humans and nature as a balance of give and take, though. Miyazaki’s portrayal of nature is unique because in his films nature is valued as far more than a resource to be bartered with. In this film, the predominant ‘civilization’ other than humans is the Ohms, massive hard-shelled insects. They display self-awareness, emotions such as anger and pain, and are able to communicate to humans through memory. They have their own values and autonomy, and live without any form of hierarchy. This film is successful in it’s portrayal of the natural world because it doesn’t strive to draw comparisons between humans or nature, or even say that nature is morally better than humans. I would say the goal of the film is to point out how limited our understanding of the natural world is as humans because we only assess nature through our own value systems and hierarchy.

Promoting sustainability is often ineffective when you are merely asking people to ‘do better’. Following Miyazaki’s approach, raising environmental consciousness should be about decentralizing humans from the narrative of the natural world while maintining that as long as humans exist, we exist in relation to the natural world, not apart from it.

Gwendolyn, M. (2015). Creatures in Crisis: Apocalyptic Environmental Visions in Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the valley of the wind and Princess Mononoke. Resilience: A Journal of the Envionmental Humanities, 2(3), 172-183, https://doi.org/10.5250/resilience.2.3.0172

Miyazaki, H., Thurman, U., Stewart, P., Lohman, A., & Olmos, E. J. (2004). Nausicaä of the valley of the wind. [United States] : Burbank, CA, Walt Disney Home Entertainment.