When you hear the term “first responder,” who do you think of? Likely, those in positions such as fireman, cop, soldier, or medic come to mind. What most people fail to understand is that us everyday people may end up having to perform first response in their lives

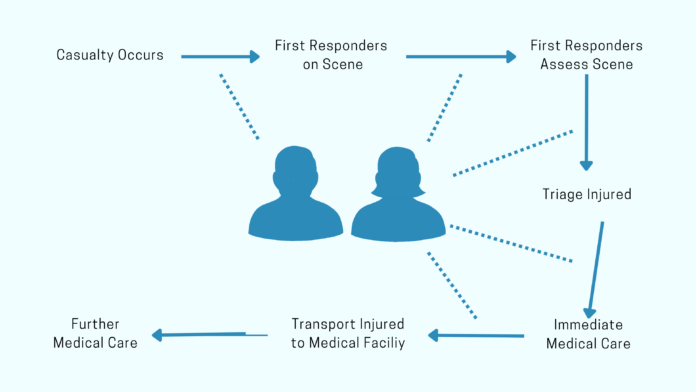

Mass Casualty Incidents (MCI) range in type, taking the form of mass shootings, natural disasters, or even global pandemics, such as COVID-19. A mass casualty incident (often shortened to MCI) describes “an event that overwhelms the local healthcare system, where the number of casualties vastly exceeds the local resources and capabilities in a short period of time” (DeNolf). Upon analysis of previous large-scale disasters, there exists an identifiable period of time between the occurrence of the casualty and the arrival of designated first response teams. In A Study of Active Shooter Incidents, 2000 – 2013, led by Pete Blair and Katherine Schweit, it was found that the average response time of law enforcement to an active shooting event was 3 minutes, and that 55% of these attacks end prior to police arrival.

Oftentimes, civilians on the scene step in to aid in casualty care during this “in-between period.”. In the event of the Morocco Earthquake, monarchical power prevented outside aid from entering and “neighbors have relied on neighbors to dig survivors out of the rubble, sharing whatever food and supplies they could. In many places, the first outside responders to show up were private organizations or citizens who had traveled from major cities to stitch wounds or hand out water” (Parker). In certain mass casualty incidents, waiting for trained first responders is not an option– time is of the essence, and a swift response can be the difference between life and death. Because the average civilian is typically untrained and inexperienced, these efforts are often improvised and do not follow any sort of protocol. Using resources that the everyday person has on hand, such as blankets or clothing, civilians have been seen making tourniquets out of t-shirts, crafting litters out of blankets and sticks, or creating neck stabilizers out of garments. This improvisation of rescue can cause further harm to the injured, leaving an area of opportunity for design to intervene.

In addition to assisting in casualty care, civilians also have historically gotten involved in the transportation efforts of the injured. The 9/11 attacks and the casualties that followed overwhelmed the available assets of designated first response teams. Response commenced on land and via waterways. As the US Coast Guard began their evacuation efforts, additional help was needed. A call was soon sent out to boat owners in the area to assist in the evacuation, leading to citizen resources being commandeered. From here, the US Coast Guard combined forces with small boats, sightseeing boats, catamarans, yachts, and ferries to assist in water evacuation. Because this allocation of civilian resources was not planned, civilians are once again forced to improvise this response effort. Though the civilian response was improvised and unplanned, the assistance of civilians during this mass casualty was crucial in evacuation efforts.

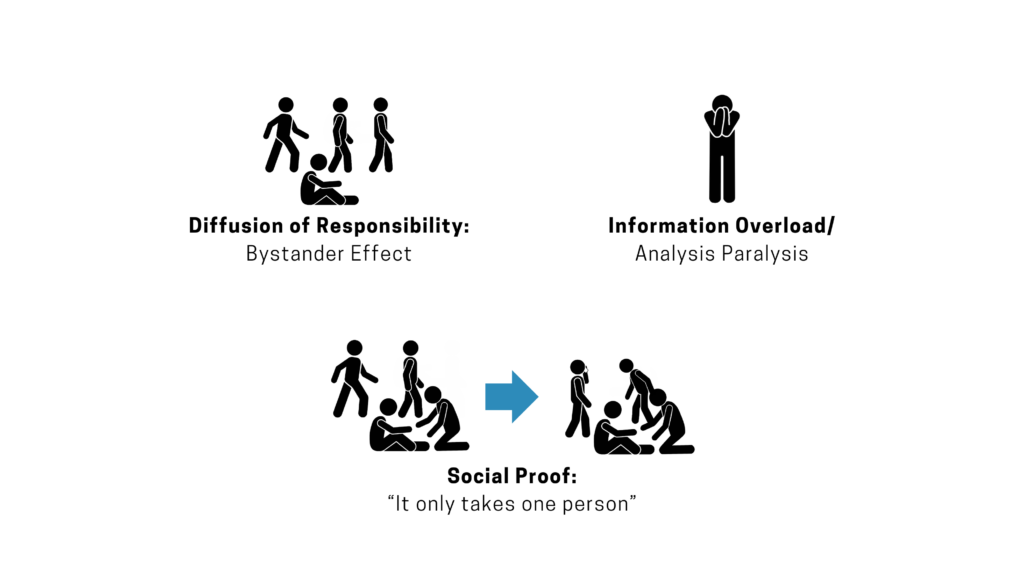

Many mental barriers can arise during mass casualty incidents, which can impact how civilians respond. When an untrained, inexperienced individual is faced with a mass casualty incident, the thought process is typically tainted with panic and fear. Information overload presents itself in times of mass crisis, and individuals who aren’t prepared for this sort of event cannot effectively make decisions when too much information is presented at once. This can lead to Analysis Paralysis, where individuals over analyze the situation to the point where the decision making hits a wall– paralysis. In such a high stress environment, such as a mass casualty incident, it is important to present the untrained civilian with a digestible amount of information that clearly defines what needs to be done.

This panic and fear can also lead to a lack of confidence within the untrained individual. Many believe that they are not capable enough to be of aid– or not as capable as others– and so they do nothing. The Bystander effect is a social psychological theory that states that individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim in presence of other people. When surrounded by many others, civilians hesitate to take action by fear of incompetence. Despite laws being put in place to legally protect the untrained civilian in the instance of providing aid to the injured, such as the Good Samaritan Laws, many hesitate to intervene due to lack of confidence in their skillset. This presents an opportunity for design to intervene; to instill a sense of confidence within the untrained responder which, in turn, will promote their response efforts.

In an attempt to further understand the civilian perceptions of mass casualty incidents and their emergency preparedness initiatives, a survey was administered to 34 individuals who do not identify as holding a position of “designated first response.” These responses reported important findings regarding personal experience with casualty response and the efforts (if any) that civilians are taking to prepare for these incidents. It was found that 35.3% of respondents feel able to perform a life-saving maneuver if necessary, and only 32.3% of respondents carry rescue equipment (narcan, bandaids, water) on a day to day basis. Secondary data collected through previous surveys further suggests this lack of preparedness with only 1 in 3 respondents reporting that they have prepared an emergency supply kit which commonly consisted of things such as flashlights, medical supplies, and water. Furthermore, it is noted that those who believe that an emergency supply kit will improve their chance of surviving a disaster are more than 3x as likely to have a kit. From this, we can gather that citizens are both unprepared in training and in resource allocation and preparation. Furthermore, the risk of these disasters has to be perceived as real in order for preparation to take place, and this preparation leads to a direct increase in the probability of survival.

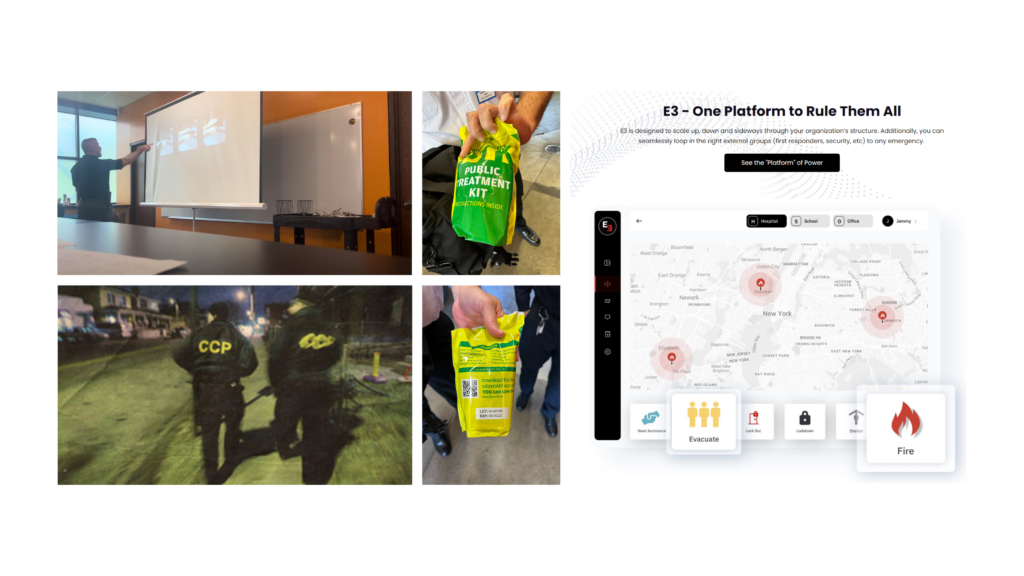

Many products and services exist today that aim to address the civilian interventions that take place. Mass casualty training, such as the CRAASE course offered through the Columbus Police Department, allows for untrained individuals to receive training surrounding the circumstances of mass casualty incidents. Courses like this spread awareness about the reality and likelihood of these events taking place, as well as certain practices that one can take in response to the situation. While a large majority of this training happens in a work or school environment in order to comply with OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) standards, the general public is able to sign up for these courses on their own accord.

Products such as public treatment kits are available for the general public, which contain; tourniquets, wound pressure dressings, gauze, scissors, mylar blanket, antiseptic towelettes, gloves, a marker, and instructions for use. These are commonly available at local fire stations or police stations in the area. Digital products have also been introduced in recent years, such as the Emergent 3 app, which is an app-based platform designed for stressful situations, and is intuitive and easy to use for all types of users. Alerts and communication allows for transparency up and down the chain of command. The Emergent 3 app has been proven successful in many armed shooting situations by providing crucial crowd-sourced data to trained first response teams which cuts down the time that these responders take to “assess the scene,” and allows for them to move directly into their response.

Research and exploration was done on civilian-facing goods in comparison to military-facing goods and hospital-facing goods. Products such as hydration packs are an example of a product which has uses in many different contextual environments. Different color palettes, materials, and shapes and sizes are used depending on the type of context the product will be used in. For a civilian-facing product or service, it must be approachable. The everyday person likely will not store away military-grade litters inside their homes. Julia Elia, a student at The Ohio State University notes that “It would make me depressed to look and think about something like that every day. I personally wouldn’t keep [a military litter] inside my house.” Products such as a litter or tourniquet evoke negative, depressing, “doomsday” emotions. If we really want to encourage everyday civilians to invest in and take home a product to aid in first response, we must design these products to evoke positive connotations that don’t make the user feel like they are prepping for a zombie apocalypse, but instead make them feel confident and capable of using them.

While these products have begun to consider civilian response to mass casualty events, there is still a great area of opportunity for designers to intervene within this problem space. I personally aim to explore this area in my design development by exploring the ways to supplement civilians with the resources that they are able to effectively use in mass casualty scenarios. As I progress through the design development phase, I will consider the following findings:

- Civilians take part in mass casualty incident response

- Civilians are untrained and inexperienced with mass casualty incident response

- Civilians often improvise in their rescue efforts

- Improvisation within rescue can lead to further injury

- Civilians experience panic during MCI, which affects decision-making

- Civilians are not confident in MCI response situations

- Civilians are generally unprepared for MCI

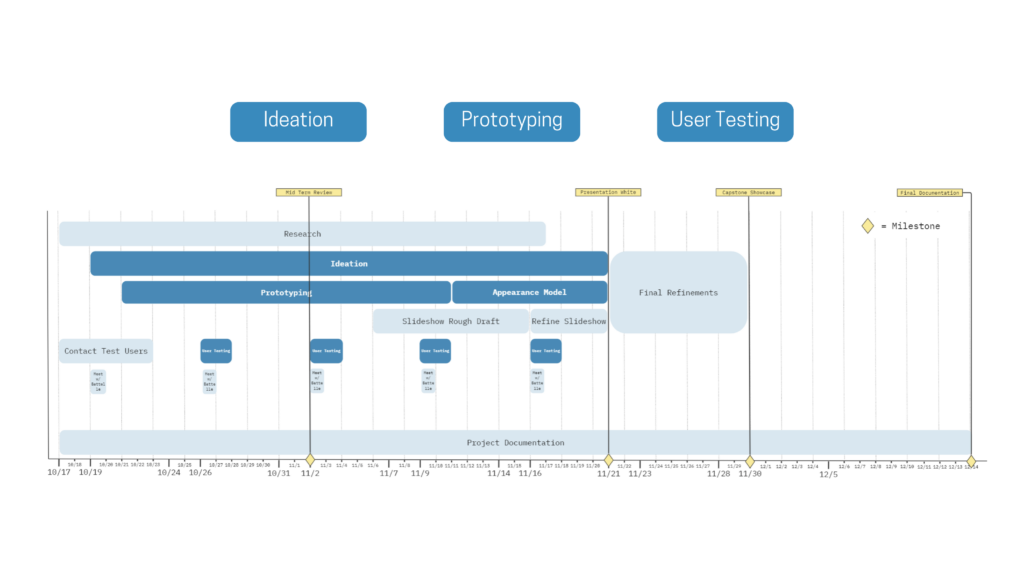

In order to keep the stakeholder (untrained civilian) front and center within the design process, I will rely heavily on user testing within my prototyping journey to evaluate the effectiveness of the resulting design. Ensuring that the design is approachable, intuitive, and transportable is key to the success and widespread implementation of the final product.

Sources:

DeNolf RL, Kahwaji CI. EMS Mass Casualty Management. [Updated 2022 Oct 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482373/

Blair, J. Pete, and Schweit, Katherine W. (2014). A Study of Active Shooter Incidents, 2000 – 2013. Texas State University and Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington D.C. 2014.

Parker, Claire. “How Rigid Government, State Neglect Hobbled Morocco’s Earthquake Response.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 13 Sept. 2023, www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/09/12/morocco-earthquake-response-aid-government/.